‘Gallantry, guts and gumption’ — The two-hour battle in the Pacific that turned a Navy captain into a legend

“This is going to be a fighting ship. I intend to go in harm’s way, and anyone who doesn’t want to go along had better get off right now."

There were a lot of badasses in World War II, but few stand above the crew of the USS Johnston, the outgunned, outnumbered Navy destroyer that charged into the teeth of a Japanese naval line during the Battle off Samar on the morning of October 25, 1944.

Despite the wall of steel in front of it, the USS Johnston fought so furiously that Japanese sailors mistook it for a heavy cruiser. The ship’s skipper, Cmdr. Ernest E. Evans, knew he had to risk it all to protect the invasion force Gen. Douglas MacArthur was landing on the Philippines. While neither Evans nor the Johnston survived the battle, their fight has since become known as one of the Navy’s finest hours.

“In no engagement in its entire history has the United States Navy shown more gallantry, guts and gumption than in the two morning hours between 0730 and 0930 off Samar,” wrote the historian Rear Adm. Samuel Eliot Morison in his book History of United States Naval Operations in World War II.

Now, almost 77 years after it sank, the wreck of Johnston has been identified nearly four miles below the waters where it last fought. At 20,000 feet deep, it is the deepest shipwreck ever discovered. While the wreck was first found in 2019, it remained unidentified until its hull number, 557, was found last month. The discovery also represents the final resting place of the 186 sailors — over half the ship’s total 327 crew — who died in the battle.

“As a U.S. Navy officer, I’m proud to have helped bring clarity and closure to the Johnston, its crew, and the families of those who fell there,” said retired naval officer Victor Vescovo, who led the mission to identify the wreck, in a statement on Thursday.

‘Melee-like conditions’

The discovery also offers a chance to re-tell the epic Battle off Samar, one which was as ferocious as it was unexpected for American sailors in the early hours of that October day. The Imperial Japanese Navy was making one last push to defeat the Allied ships off the island of Leyte in the central Philippines. In a surprise maneuver, a heavy task force of four Japanese battleships, six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and 11 destroyers swung into a lightly defended American sector of Leyte Gulf, according to an official U.S. Navy account of the battle.

When the two fleets met in the early hours of October 25, Johnston led its fellow destroyers, the USS Heermann and USS Hoel, into enemy guns, and the Johnston actually managed to damage a Japanese heavy cruiser. While the Johnston itself was also heavily damaged by 6- and 14-inch shells, the psychological blow dealt to the Japanese force made it well worth the effort.

“The determined, aggressive attacks of the three U.S. destroyers, coupled with the ongoing air attacks on his ships, tended to confirm [Japanese Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita]’s erroneous assessment that he was facing a strong carrier task force,” wrote expert Carsten Fries in an article for the Naval History and Heritage Command. “The second U.S. torpedo attack would only strengthen this impression.”

The conditions were “melee-like,” Fries wrote, as U.S. and Japanese ships zig-zagged and shot guns and torpedoes at each other. But Johnston put out such heavy fire that Japanese sailors thought she was a heavy cruiser, he said.

As the battle raged on, Johnston ran through all of its torpedoes, so instead it fired its 127mm guns at the Japanese cruisers. The American destroyer somehow managed to repulse a wave of enemy ships, but by this point Johnston was limping on one engine. Japanese destroyers concentrated fire on the damaged ship, leaving it dead in the water, and Evans gave the order to abandon ship at 9:45 a.m. Though fatal, Johnston’s fight helped save the American landing force sent to invade the Philippines.

“Evans’s aggressiveness, along with that of other American destroyermen and aviators … led the Japanese to believe they were facing a much larger force and caused them to turn away,” wrote Robert J. Schneller, Jr. in a blog for the Naval Historical Center

The fight is even more remarkable considering that Johnston’s skipper gave his life for a country which often discriminated against him simply because he was Native American.

‘The skipper was a fighting man‘

Because of his heroism that day, Cmdr. Ernest Evans was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, becoming the first Native American in the U.S. Navy and one of only two destroyer captains in WWII to receive such an award. Born poor and Cherokee in Oklahoma, Evans “beat what seemed impossible odds” and intense prejudice against Native Americans to wind up a Naval officer, Schneller wrote. Evans graduated from a nearly all-white high school, joined the National Guard, transferred to the Navy enlisted service, won an appointment to the Naval Academy without political pull, and graduated with the class of 1931. Twelve years later, Evans told his men aboard Johnston that he would expect a similarly high performance.

“This is going to be a fighting ship. I intend to go in harm’s way, and anyone who doesn’t want to go along had better get off right now,” Evans said on Oct. 27, 1943, at the commissioning ceremony of Johnson, according to retired Rear Adm. Sam Cox in a blog for Naval History and Heritage Command, of which Cox serves as director.

Despite his fighting words, Evans “never exploded in anger and seldom upbraided a subordinate in front of others for poor performance,” Cox wrote. But when the superstructures of the Japanese ships appeared over the horizon in the Leyte Gulf, Evans didn’t wait for orders before ordering a torpedo run against the enemy, despite having only two hours of fuel left.

“All hands to general quarters. Prepare to attack major portion of the Japanese fleet,” Evans said, according to Cox. “All engines ahead flank. Commence making smoke and stand by for a torpedo attack. Left full rudder.”

Later on in the fight, Evans saw the Japanese had targeted the escort carrier USS Gambier Bay, and he proceeded to give what Johnston’s gunnery officer, Lt. Robert Hagen, called “the most courageous order I’ve ever heard: ‘Commence firing on that cruiser, draw her fire on us and away from Gambier Bay,’” Cox wrote.

Though Gambier Bay was sunk, the effort further highlights the heroism of Evans and his crew.

“The skipper was a fighting man from the soles of his broad feet to the ends of his straight black hair. He was an Oklahoman and proud of the Indian blood he had in him,” Hagen said, according to Cox. “The Johnston was a fighting ship, but he was the heart and soul of her.”

Evans’ reputation continues to inspire sailors to this day.

“I wanted to be part of the history that included people like him, and that is why I joined the U.S. Navy,” Cox wrote.

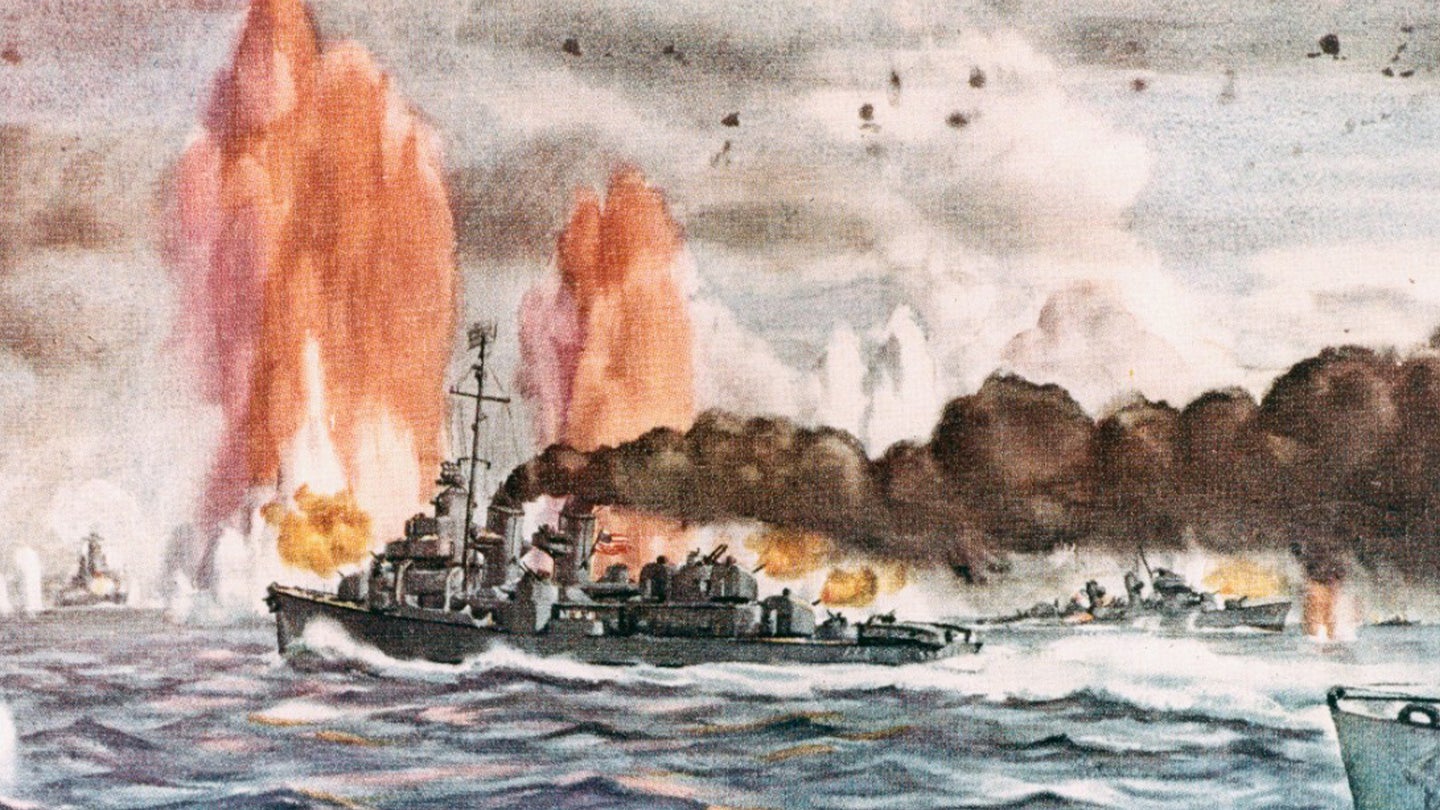

Featured image: “Battle off Samar, 25 October 1944” – Watercolor by Commander Dwight C. Shepler, USNR, depicting the counterattack by the escort carrier group’s screen. Ships present are (L-R): Japanese battleships Nagato, Haruna, and Yamato, with salvo from Yamato landing in left center; USS Heerman (DD-532), USS Hoel (DD-533) sinking; Japanese cruisers Tone and Chikuma.

Related: Watch this Navy veteran shrug off batons and pepper spray like a badass amid protests in Portland