The U.S. military has stood perpetually accused of not fielding new weapons to troops fast enough since at least the Civil War, when the Union Army took years to replace muzzleloaders with obviously superior repeating rifles.

And when new weapons finally do make it to the front lines, complaints that they are ineffective in actual combat usually follow. The M-16 controversy is a perfect example.

It would be easy to blame such problems on the indifference or outright ignorance of “the brass.” The truth, however, is much more nuanced than that, according to Richard S. Faulkner, the William A. Stofft chair of military history at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.

Faulkner spoke with Task & Purpose at length about the financial, logistical, and practical factors that determined when and how the U.S. military fielded small arms from the Civil War through the Vietnam War. The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

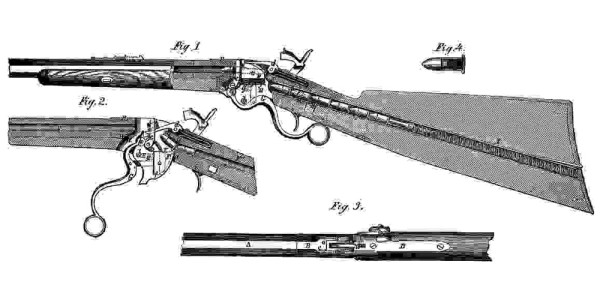

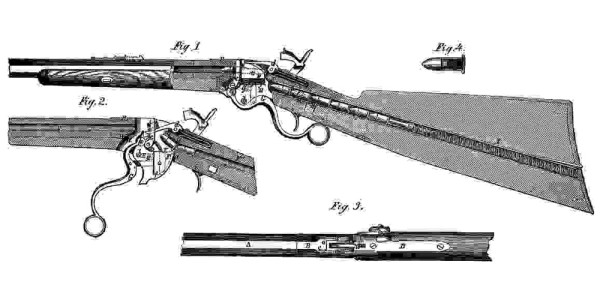

Q: If repeating rifles were available at the start of the Civil War, why did the Union Army continue to use muzzleloaders for the first three years of the war?

The issue had little to do with doctrine. The real sticking points were logistics, money, and the ugly realities of trying to expand an army from 16,000 to over a million men. The supposed “villain” in this tale is the Union Army’s Chief of Ordinance, Brigadier General James Ripley. In response to a query from the Secretary of War about buying Henry and Spencer rifles in late 1861, Ripley pointed out logical and practical reasons for not buying the weapons. He worried about the reliability of both weapon’s magazine systems, the cost of the rifles and ammunition, and inreasing the already troublesome number of different types and calibers of ammunition in the army. While he was conservative in his bent, he had good reasons for being cautious.

Neither the Henry nor the Spencer had undergone much testing in the field, and neither company was ready for anything approaching the mass production required to arm a rapidly expanding army. In 1861 and 1862, the Union needed weapons immediately —not sometime in 1863 or 1864.

Both the Henry and the Spencer were more than three times the cost of a traditional rifled musket. Marcus Tullius Cicero had it right when he noted that, “The sinews of war is infinite money.”

The adoption of repeating rifles would also have saddled the Union Army with deep logistical burdens. Repeating rifles supply lead to more ammunition consumption. The combat load for a muzzle-loading rifle equipped infantryman was 40 rounds. Both armies during the war expected that this basic load would be sufficient for a day of fighting. The 16- shot Henry could easily that supply in less than four minutes of firing.

Although the repeaters offered a firepower overmatch against the Confederates and the possibility of revolutionizing tactics by allowing soldiers to lay down while firing and spreading out formations for safety without sacrificing volume of fire,these changes required a large degree of additional training and discipline in the individual soldier. Also, a soldier with the issued musket tool could perform most of the repair on a rifle musket in the field using the simple musket tool issued with their weapons. Any damage to a repeating rifle required access to a much wider array of parts and the service of a trained armorer.

Q: The Krag rifle used during the Spanish-American war was slow to reload. Was that so that soldiers would not burn through their ammo too quickly?

When the Army adopted the metallic cartridge rifle following the Civil War, officers were rightly concerned about ammo conservation. The single-shot Trapdoor Springfield seemed to be the solution to the problem. However, when the French fielded the M1886 Lebel smokeless powder cartridge, bolt action magazine rifle, every other military rifle in the world was made obsolete.

The 30-40 Krag had a five-round magazine that required the soldier to load each cartridge into the magazine compartment by hand. However, Army officers were still worried about their soldiers burning too rapidly through their ammunition. The Ordinance Department’s solution was to build a “magazine cut off” into the rifle.

When the “cut off” was engaged, the soldier was forced to load one round at a time into the chamber. When the “cut off” was disengaged, the soldier could rapidly fire off the five rounds in the magazine. Soldiers were only to disengage the “cut off” when ordered to do so by their leaders.

The problem with the Krag’s slow rate of fire became evident during the Spanish-American War. Some of the Spanish were equipped with the M1893 Spanish Mauser rifle. This rifle was loaded using a five-round stripper clip which allowed the firer to shove five rounds into the weapons internal box magazine in a few seconds rather than fumbling with individual cartridges. This gave the Spanish an increased rate of fire over the Americans.

The issue of fire control did not go away when the Army discarded the Krag. The M1903 Springfield rifle also used a magazine “cut off,” and the M-16A2 rifle adopted by the USMC and the Army in the 1980s replaced theweapon’s full automatic feature with a three-round burst. The change to the M-16A2 was intended to conserve ammo while also giving the firer better control of their weapons.

Q: I thought the Browning Automatic Rifle was not fielded during World War I because the Army feared it would fall into German hands, but it appears that U.S. soldiers did, in fact, use the BAR in France in 1918. Am I wrong?

The BARs did see limited use in World War I. Although there may have been some concern in the AEF’s high command about the weapon falling into German hands, the overwhelming reason why more of the BARs did not see action in the Great War were problems with production. In 1917 and 1918, the American arms industry was already overwhelmed by producing weapons for the Allies and manufacturing basic rifles for the millions of men entering the Army. It simply took too long for the companies making the BARs (Colt, Marlin-Rockwell, and Winchester) to retool and open up new production lines to mass produce the weapons.

A few of the late arriving divisions, such as the 79th and 36th, did use the BARs in combat. I have been going through first-hand accounts of soldiers from the 36th Division from the National Archives. The soldiers were unstinting in their praise of the weapon. Corporal R. A Hurst, of the 141st Infantry, wrote. “We were the only ones that ever used the Browning Machine Rifle in battle. It worked wonderfully. The Germans having never seen or heard of this rifle, they were scared to death and we captured many prisoners.”

Another soldier in the regiment, Corporal Edwin McNeely, reported, “I might mention the Browning Automatic Rifle. The enemy couldn’t stand before it, and it was the most effective weapon we had, not having any of the rifle grenades or hand grenades either. The browning A.M. Rifle was the winning factor in the battle that day. It is in my appreciation the best rifle ever made.”

Q: Is it accurate to say that the problems with the M-16 during the Vietnam War were due to design flaws that have since been corrected? I ask because soldiers were able to ameliorate but not eliminate many of the issues with the rifle by cleaning it several times a day.

There were a number of reasons for the jamming problems with the first M-16s in Vietnam, but most of them have to do with the Army’s messing around with Eugene Stoner’s original design and choice of ammunition. From the beginning, the Army Materiel Command and the Ordnance Corps were biased against Stoner’s original AR-15 design. Army weapons specialist objected to the design due to its small caliber (.223 vs .30) and the fact that the AR-15, unlike the M-14, was not an “in house” product.

The Army grudgingly adopted the weapon as the M-16, but only after adding unnecessary features such as a manual forward assist to force the bolt closed if the weapon did not feed and changing the spiral twists in the AR-15’s rifling. The worst thing that the Army did, and the one thing that most directly led to the jamming problem in Vietnam, was changing the powder used in the cartridge.

Stoner’s original design used a propellant known as IMR 4475 (Improved Military Rifle 4475), but the Army complained that this powder did not produce enough muzzle velocity to meet its needs. The Army decided on a cartridge filled with the standard M194 ball powder that it had used in its small arms cartridges since World War II (and which the Olin Company already had in abundance). The use of this powder led to a much greater degree of fouling in the M-16’s gas port than the IMR 4475. Furthermore, the “hotter” propellant of the M194 ball powder led to a greater cyclic rate in the M-16, which in turn caused increased jamming, wear, and breakdowns in the weapon’s mechanism.

Reports from Vietnam of the M-16 jamming in combat led to a congressional investigation in 1967 (the Ichord Committee). First the Army belatedly issued a proper cleaning kit and better instruction on cleaning the weapon to help reduce jamming. In the face of growing pressure, the Army Ordnance Corps made some reluctant changes. These included altering the buffer system to slow the M-16’s rate of fire, chroming the chamber and bore, and making minor changes to the cartridge to reduce fouling.

Further modifications to the basic M-16 design and changes in the weapons cartridges since Vietnam slowly overcame most of the technical problems that had caused jamming. However, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have produced more complaints from soldiers and Marines about the reliability of the M-4 and later versions of the M-16. Part of the problem is that the tight tolerances inherent in the design and manufacturing of the weapons simply mean that they require a lot of pampering and constant cleaning when they are used in dusty sandy environments.

WATCH NEXT:

Dr. Richard S. Faulkner the William A. Stofft Professor and Chair of Military History at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. He served 23 years in the U.S. Army and commanded a tank company in the 1st Armored Division during Operation Desert Storm.