There’s no roadmap for getting out of the military. You sign your terminal leave papers, toss your reflective belt into the dumpster, hop in your car, and race through those front gates like you just robbed a bank. Poof, you’re a civilian again. Now what?

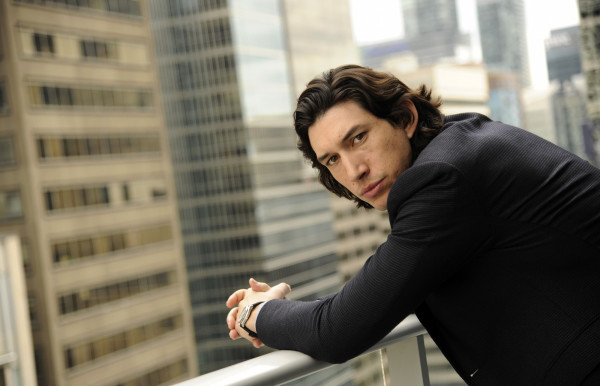

For Adam Driver, who most people now know as Kylo Ren in “Star Wars: The Force Awakens,” the answer was obvious: show biz.

Driver enlisted in the Marine Corps shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks and was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines as an 81mm mortar man. Less than three years later, he was medically discharged following a mountain biking accident that broke his sternum.

War wasn’t in the cards for Lance Cpl. Driver. So he made his way to The Juilliard School in New York City to study drama. Meanwhile, the Marines he had spent the last few years training with deployed to Iraq. But they stayed in touch

“They were like, ‘Wait, what the fuck are you doing? Wearing pajamas and dancing all day?’” Driver recalled in an interview with Task & Purpose. “And I’m like, ‘Uh, yeah, but it’s the foxtrot.’”

The pajama party paid off. After landing a leading role on the HBO hit series “Girls,” Driver quickly established himself as a heavyweight in New York’s hipster-oriented acting scene, mastering the persona of the brooding anti-hero who understands poetry, but can still kick your ass in a fistfight. It’s hard to imagine anyone else playing Kylo Ren.

Related: This former infantryman will be the villain in Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens »

The irony of going from enlisted mortar man to Brooklyn-based millennial sex symbol is not lost on Driver. He’s still a little bit of a grunt at heart. In 2006, he founded Arts In The Armed Forces, a nonprofit organization that puts on free modern theater performances for service members on American military bases around the world.

“I don’t have to salute anybody and nobody can tell me what to do,” Driver joked. “But really, it feels like I’m continuing my service, just a more cushy version of it. I love the people I got to serve with. This is about them.”

Task & Purpose spoke with Driver about his mission to bridge the cultural gap between the armed forces and the arts community, how the Marines primed him for success in civilian life, and getting chased by a militia through the streets of Tijuana.

Why did you decide to start Arts in the Armed Forces?

When I began attending Juilliard, I noticed a huge change in myself coming not just from a military background, but from a background in the Midwest, where communicating feelings really wasn’t a priority. Suddenly I was exposed to playwrights and these characters and these plays. And for the first time, I became aware of the value of expressing yourself and putting language to feelings. It felt like that was missing from my military experience. Not that I thought people should sit around and share feelings all of the time, but there was no real avenue for us. The entertainment we were exposed to at the time, while it was all well intended, was slightly condescending. It was like winning dates with cheerleaders and somebody singing songs about how America is great — which I totally agree with and believe — but I just felt like we were capable of handling something more thought-provoking. So I went to veterans organizations that were already established to see if we could do it. Everyone kept telling me that theater really didn’t fit the military demographic. So, really, more than anything, anger spurred this nonprofit.

Why do you think those people thought service members wouldn’t be responsive to this kind of stuff?

I think people just associate the military with violence and structure and discipline, and they also have stereotypical views of the theater as being just about feelings and emotion. I think there are a million factors at play that keep these two worlds apart, which is ironic since the very birth of theater started in direct relationship to the military. Aeschylus, Euripides — those ancient Greek playwrights were also military generals who wrote plays about the military for an audience of people who were at war on six or seven fronts. So it was once part of the military culture and more and more over the years it’s turned into a stereotype of a touchy-feely kind of thing, while the military has gained a reputation for being the opposite.

What are you hoping the service members in the audience are getting out of these performances?

I can only speak for myself and what people have said to us afterwards, like, “I’ve never gone to see a play,” or “plays are too expensive,” or “I didn’t know theater was like this.” Our material isn’t military-themed. We stay away from that to really highlight the human struggles we all share, as opposed to just telling a military audience what it’s like to be in the military. When people think of Shakespeare-types, they think the language is over there somewhere — that it’s not in their world. But the characters are actually easily accessible and wildly articulate. And also, the way that we do it, how it’s very pared down — not sets, no costumes, no lights, just reading the material — shows the military audience that there doesn’t need to be this huge artifice. There doesn’t need to be a theater. They can do it anywhere.

Do you hope there are guys like in the audience? Young service members who are curious about the arts but never really had the opportunity to explore it?

Yeah, I am hoping for people who are artistically inclined or are curious about it, but who never had the avenue to explore it. And I’m also hoping for people who would’ve never been exposed to a play because of their background. I know that there are both of those people because they come up to me afterwards, like, “I’ve always been interested in acting,” or “I did acting in high school before I joined the military,” or “I was always curious about it but never pursued it.” And then there are people who approach us afterwards and are like, “I never thought, being from where I’m from, that this is something I’d ever be exposed to.”

What’s the most practical advice you’d give a young Marine who was thinking about pursuing a career in acting?

Everybody is so different, so it’s hard for me to say. So I can only say what I did, which was that I went to school after I got out of the military. That was great for me, because I really didn’t know anything about the theater. To have three or four years to focus on your craft. Transitioning out of the military is a mindfuck anyways, so to go into a structured school setting was really helpful. To go from one intense, structured institution into another was a good transition for me. As opposed to just going straight into a civilian world. So that’s the advice I would give: going through the steps and learning the craft, instead of just expecting that now you’re going to be an actor, and now you’re going to do movies, and it’s all going to happen immediately.

Did you feel like an outsider at Juilliard?

Yeah. People were definitely scared of me, and I think part of that’s because people in my class needed to grow up a bit. I was a couple years older than they were and had this kind of intense life experience. I think they treated me with kid gloves, like at any minute I was going to fly off the handle. But I also needed to calm down a bit and be a bit more accepting of civilians. I was kind of aggressive, because I was used to talking to infantry Marines, where there’s a sort of shorthand and a roughness to communicating with each other. You’re also so jealous of civilians who didn’t decide to go to the military after high school. You always imagine them having a great time in college — you know, doing drugs and meeting girls and all of this stuff that you’re not doing in the military. I felt a sense of entitlement because I had gone through this thing and these nasty civilians were so lazy. But that’s not a fair assessment. It’s actually judgmental, so I think I needed to get over that and be a bit more accepting.

Does your military service continue to influence your work ethic?

Yeah, it’s huge. On just a very basic level: the amount of things you can do in a day. I definitely learned that from being in the military, even though a lot of it is hurry up and wait. But what I learned you can accomplish in a day makes the work required for acting seem a little less daunting. Acting is not easy, but showing up on set and being supported, working a 16-hour day, compared to the military it’s not that hard — at least as far as the physical part of it. Maybe I’m oversimplifying it. Then there’s the teamwork part of it. That’s the biggest thing I took away from my military experience. A group of people working as a team, trying to accomplish something that’s not all about one individual person. It’s all kind of a team thing it’s not about you. You just have a role and you should act your role and support the people around you. That’s the biggest thing that I’ve applied from my military background to this job.

Do you still keep in touch with the guys you served with?

I do, yeah. They’re actually getting together for a reunion this coming November and we trade texts and talk on the phone every once in awhile.

Got any funny stories from the Marines that you’d be willing to share with us?

That are appropriate?

Hey, this is a military audience you’re talking to. It can be R-rated.

Yeah, but it’s the people outside those fuckers that I’m worried about . It’s mostly just adventures in Tijuana. Getting chased by a militia in Tijuana, that’s what I remember. In boot camp, I just think of drinking water until everyone puked. Mostly just pain and misery. I remember one of the first days, when everyone is being processed and getting their haircut. They’re shaving everyone’s head for the first time. And if you’ve never had your head shaved before, like me, you’re not really familiar with the topography of your head. All the dents and curves and stuff. I remember there was a guy who was going before us, and everyone was just looking at the head of the guy in front of us, and suddenly we just hear this scream. The guys who are shaving the heads aren’t barbers. They’re just like some PFC or lance corporal they grabbed and were like, “Shave these fucking heads.” And one of them shaved a mole off someone’s head, and he started bleeding and screaming. So everyone in line starts subtly touching their heads to check to see if they had any stray moles they forgot about. And of course there’s some drill instructor yelling, “Don’t touch your fucking heads!”