Digital messaging is ruining everything. Friendships.Relationships. Work and productivity. The art of conversation. Now, finally, we can add the U.S. Navy to the list.

That’s the thesis of the generational pearl-clutching published in the May 2019 issue of Proceedings, in which Navy Capt. John L. Bub, Jr., director of operations and training for Tactical Training Group Atlantic (TTGL), argued that the “highly distracting” chatrooms utilized by sailors aboard Navy vessels are a sinister threat to surface operations that desperately require our attention.

“Don’t text and drive has been ingrained in our collective consciousness. Distracted driving is the number one cause of accidents in the United States, and the number one distraction causing those accidents is drivers texting on their mobile phones,” opens Bub. “On warships at sea, watchstanders face a similar problem—they all have the ability to, and are even required to, communicate through message chat rooms on computers at their watch stations.”

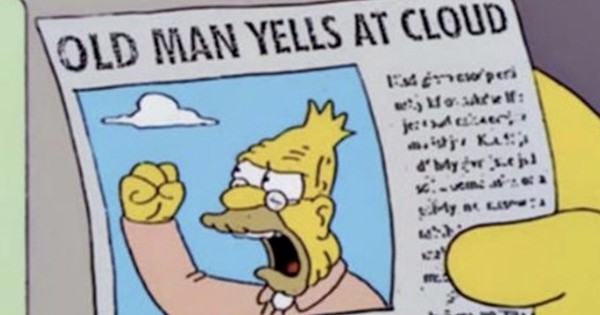

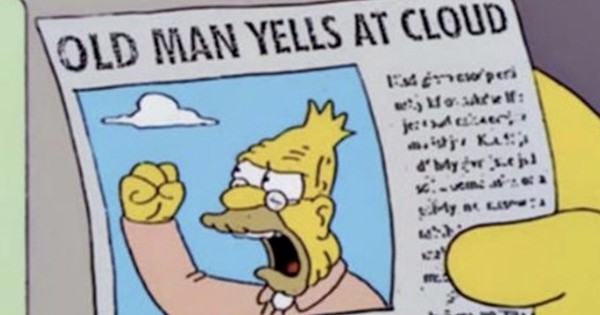

Yes, true: Distracted driving kills more than speeding or booze when it comes to car accidents, and the same logic that applies to your Ford should probably apply to a multimillion-dollar warship. But Bub’s thesis quickly devolves into his best impression of bewildered septuagenarian Abe Simpson from the titular animated comedy (emphasis ours):

Despite the ubiquity of information today and the sophisticated information technology systems afloat, staff tactical watchstanders remain severely challenged in maintaining an accurate picture on tactical displays.

Most watch stations now have chat rooms that watchstanders are required to monitor along with their console display. Young watchstanders are very comfortable monitoring chat rooms, but less comfortable monitoring radar. This is like being more comfortable texting than looking out a car’s windshield while driving. They are even less comfortable talking on the radio, though doing so would better allow them to communicate while simultaneously monitoring their tactical displays. Communicating through text as opposed to verbally reflects the pervasive presence of digital media in today’s society. Furthermore, this trend away from verbal communication and the decline in professional, competent radio procedures has been exacerbated by the elimination of the Radio Users Telephone Handbook to train watchstanders

“When the fight starts and missiles are flying, watchstanders may only have seconds to react and save the ship,” he concludes. “My great hope is that if that happens the watchstander will be looking at the tactical display and not the chat window.”

So let me get this straight: in the event of an imminent collision (like, say, the car crash situation Bub invoked in his opening graf), young watchstanders won’t call for help because … they’re more comfortable texting than calling for help over the phone?

Look, it’s certainly true that younger generations prefer text to talking, but Bub’s only evidence that this is directly impacting surface operations is, well, “I have mentored and evaluated many ships and watchstanders.” Luckily for us, we have two years of Navy investigations into the back-to-back mishaps of the USS Fitzgerald and USS John S. McCain to provide some real-world insight in to how watchstanders react in times of crisis.

First, let’s take a look at the “dual-purpose investigation” into the Fitzgerald collision by Rear Adm. Brian Fort and obtained by Navy Times in January 2019:

[The USS Fitzgerald’s] Voyage Management System that generated more “trouble calls” than any other key piece of electronic navigational equipment. Designed to help watchstanders navigate without paper charts, the VMS station in the skipper’s quarters was broken so sailors cannibalized it for parts to help keep the rickety system working.

Since 2015, the Fitz had lacked a quartermaster chief petty officer, a crucial leader who helps safely navigate a warship and trains its sailors — a shortcoming known to both the destroyer’s squadron and Navy officials in the United States, Fort wrote.

Fort determined that Fitz’s crew was plagued by low morale; overseen by a dysfunctional chiefs mess; and dogged by a bruising tempo of operations in the Japan-based 7th Fleet that left exhausted sailors with little time to train or complete critical certifications.

So the equipment was broken and the Fitzgerald crew were exhausted and hated their lives — sounds about right. How about the McCain? According to the Navy, the problem wasn’t screen obsession but bad training, per Navy Times:

[The] McCain’s bridge team was neither experienced nor qualified to the level they should have been to be steaming a warship through crowded waters, and the Navy’s report acknowledged as much, blaming the failures on the bridge team’s insufficient local training and qualifications.

That’s because multiple members of the bridge team on watch at the time of the collision were temporarily assigned from the cruiser Antietam and had never officially qualified to operate the bridge equipment on board McCain.

The report noted that the differences between the two ship’s steering systems were significant, but none of the watch-standers were given any training to learn the new system.

I’m sorry, Bub: I trust your experience, but levying this argument without even the slightest bit of anecdotal elaboration seems eerily reminiscent of somebody stewing over being snubbed by their granddaughter’s dinnertime iPhone use. Time comes for us all — just embrace it.

Read the whole article on the U.S. Naval Institute website here.