The Navy is finally going to let you get the sleep you need while you’re out at sea, assuming everyone follows the guidance the service just put out.

According to a recent Navy press release, the instruction is aimed at ensuring sailors in its surface fleet get enough sleep on a consistent basis so they can effectively and safely do their jobs at sea.

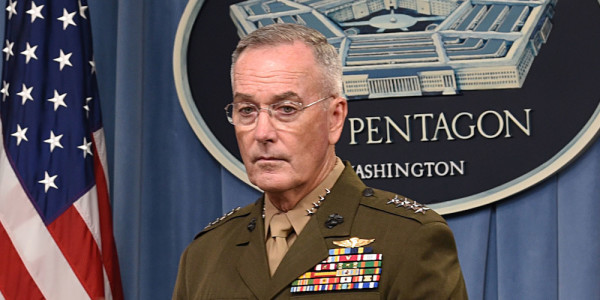

“With this instruction, we wanted to provide commanding officers and ships with a means to better manage their workday and watch rotation to improve crew endurance,” Dr. John P. Cordle, the human factors engineer with Naval Surface Force Atlantic said in the release.

The Comprehensive Endurance, Fatigue Management Program Instruction was released on Dec. 11 and builds off of existing guidance published in 2017.

“A couple things improved in the new instruction: tightening it up and making crystal clear what the priorities are: warfighting, readiness and elite performance,” said Cordle, himself a retired Navy surface warfare officer. “Secondly, we address the fact that a vast majority of mishaps are traced back to human factors and human error. We added an enclosure to capture all of the best practices, good ideas and feedback from fleet operators and scientists, and even included some thoughts on exercise, sleep and nutrition. We looked at the topics in a more holistic way, after having more time to flesh it out.”

The end result: The Navy wants its sailors’ sleep schedules to align with the body’s natural circadian rhythm, which typically means going to bed at the same times each day, and standing watch at the same time every 24-hour-cycle.

The instruction requires vessels with Naval Surface Force Atlantic and Naval Surface Force Pacific implement watch rotations that align with the circadian rhythm, and develop a support schedule to ensure that watchstanders are actually getting their allotted period of sleep when they’re off “no matter when they have watch,” said Cordle.

Video: Sailors explain Navy slang

The circadian watch rotation can be implemented in a number of ways, according to the release, such as a three-on/nine-off rotation in four sections, or a four-on/eight-off rotation in three sections.

The watch change isn’t just about getting sailors more sleep — though, yes, that’s an important part — it’s about maintaining a consistent sleep cycle. Switching to a circadian rhythm watchbill has resulted in improved performance, and better morale on ships where it has been implemented.

The circadian rhythm is a 24-hour cycle that is part of the body’s internal clock, and it’s essential for the body to function properly. Fatigue coupled with an inconsistent sleep schedule can have detrimental short-term and long-term effects on the body, as well as the mind. In the short-term it can adversely affect mental health, and undermine your ability to concentrate and learn.

“Now, science shows the long-term negative effects of sleep deprivation, including diabetes, weight gain, heart disease, and even cancer are linked to a lifetime of non-circadian (lifestyles), called circadian-scarring” Cordle said.

The new instruction, like the previous one, comes with an individual risk management tool, which tracks things like a sailor’s watch-to-rest ratio, their experience level with the watch station they’re manning, and the condition of the equipment they’re using. It also includes a list of additional questions that need to be asked of watch standers, like “have you read the instructions?” and “has anyone had issues with this procedure before?”

The Navy’s efforts to overhaul its watch-standing procedures began after the at-sea collisions of the USS John S. McCain and the USS Fitzgerald in 2017, which occurred just months apart and resulted in the deaths of 17 sailors. Fatigue was determined to have played a role in the collisions, among other issues. Investigations into the incidents found that many of those standing watch were doing so on little or no sleep during critical maneuvers, like strait transits, USNI News reported in 2019.

“None of the solutions are simple, but they are doable,” said Cordle.

“If you work too hard, don’t sleep, don’t eat properly, and don’t exercise, you’re going to be unfit, and there’s going to come a time when you’re the last person between your ship and disaster,” Cordle said. “And you’re going to make a bad decision because you let yourself get in a bad place, and somebody could get hurt or killed. You’ve let the crew down.”

Consistency is key to maintaining a circadian rhythm, though sometimes service members may wake up a bit too early because the Chief needs them to sweep fore and aft or the CO wants to know why the Keurig won’t work.

Responding to the unexpected is a part of military life; it’s also why there’s that clause at the bottom of everyone’s enlistment paperwork laying out that the “needs of [SERVICE]” will basically supersede all else. While that makes sense in combat or during an emergency, it sometimes gets taken advantage of, or stretched.

That’s where the new regulation raises some eyebrows: It operates on the premise that everyone, particularly leadership, will respect those new regs and allow their sailors to adhere to them.

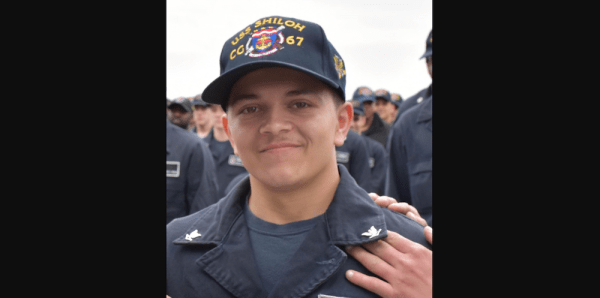

“Look, this instruction is great and shows that the Navy is listening and taking action to better protect sailors’ lives and the expensive equipment they operate and maintain,” said Shawn VanDiver, a former Navy fire controlman who served aboard the USS Thach from 2003 to 2008 and the USS Chancellorsville from 2011 to 2013.

“That said, the only way this instruction is adhered to is if there is buy-in throughout the chain of command and a reliable way to enforce the rule. It would be nice to see a study two years from now that measures the impact across a litany of metrics, including quality of life, systems readiness, and more.”

“This is only going to be as good as the chiefs and officers on every ship — if they adhere to it,” said VanDiver, who was quick to point out that while it may not be official Navy policy for sailors to stay up for 30 hours straight trying to get a piece of equipment repaired, as he and many other sailors have, it’s part of the culture.

“The instruction has changed, the culture needs to shift with it,” VanDiver said.

But the changes to the watch-standing protocols that the Navy has rolled out in recent years seem to be leading in the right direction.

“This is about reinforcing a mindset and a culture that is people-centered,” Cordle said in the press release. “You would never consciously skip a planned maintenance check on your gear. Well, our daily maintenance check on our body is sleep. Skipping that is just as bad as not maintaining your equipment.”

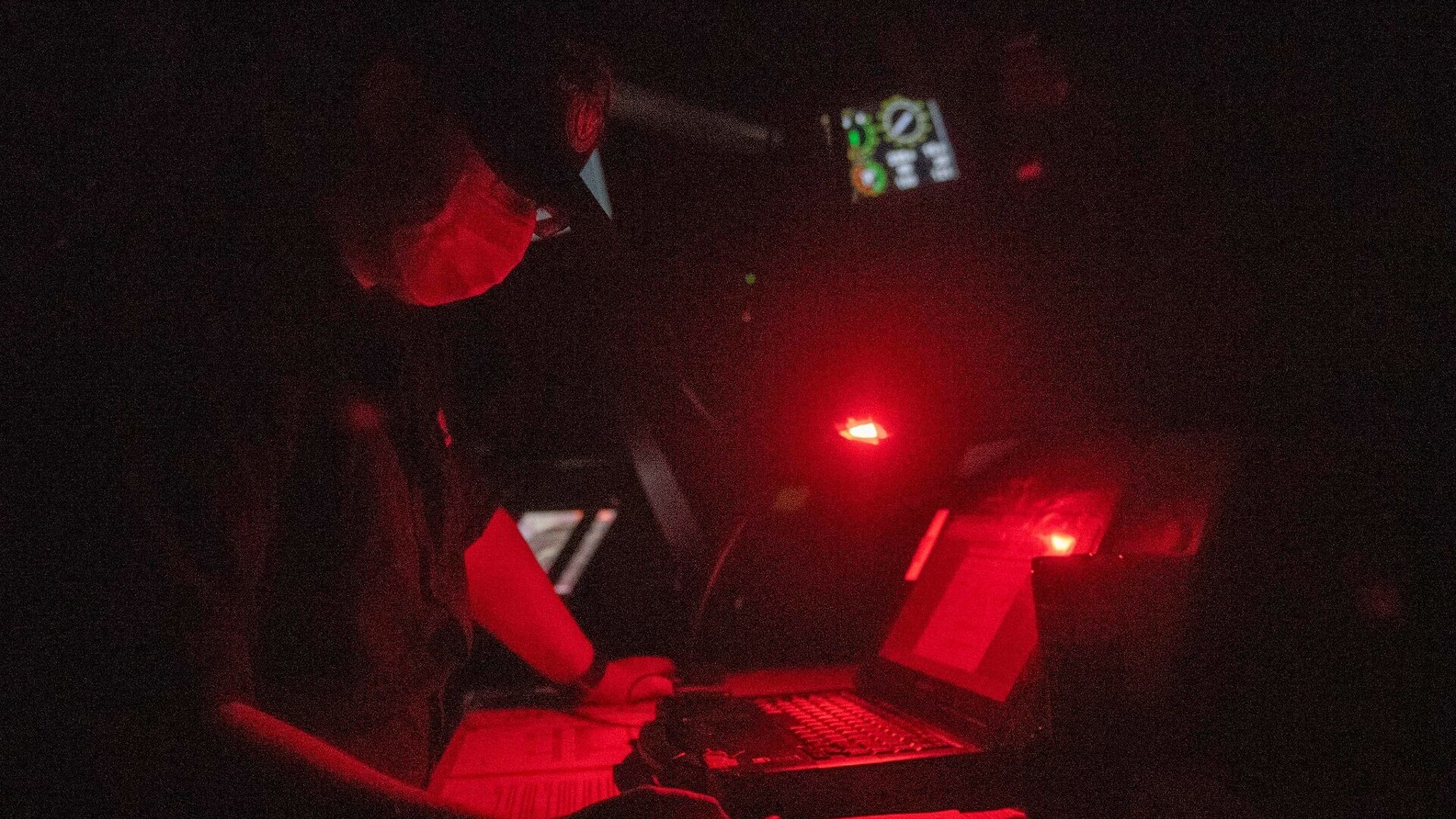

Feature image: Quartermaster 1st Class Jacob Worden, from Bolingbrook, Ill., stands Quarter Master of the Watch at night on the bridge of the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Barry (DDG 52). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communications Specialist Seaman Molly M. Crawford)