“Since World War II, Israel has assassinated more people than any other country in the Western world.” — Prologue

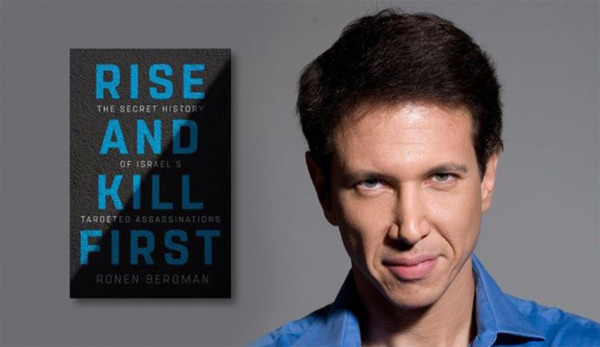

Two things about Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman immediately jump out: It is, in the words of its subtitle, about “the secret history of Israel’s targeted assassinations” and, at almost 800 pages (including endnotes and index), it’s a giant brick of a book.

A brief note on terms. Bergman says that whatever we call it — extrajudicial killing, killing the driver, liquidation, targeted killing, assassination, arranging meetings with God, etc. — it comes down to the same thing, “killing a specific individual to achieve a specific goal.” In Bergman’s hands, the dense detail, long timeframe, and heavy moral seriousness of the topic are delivered at a page-turning pace.

Shifting perspective between a detail and its importance is fundamental to how Bergman unfolds information and echoes an equally important shift he makes: writing as an outsider with insider information about deeply secretive organizations and operations that are run by deeply secretive people. Bergman, an Israeli journalist, is senior correspondent for military and intelligence affairs at Yedioth Ahronoth; he also brings his education in the law and history to his writing. Today, American and English-language audiences may recognize him as the author of The Secret War With Iran or as a New York Times contributor, where he’s penned recent articles on Black Cube’s investigation into Ben Rhodes and Colin Kahl and on the Trump Tower meeting on August 3, 2016, between Donald Trump Jr, Joel Zamel, Erik Prince and George Nader. In his “note on the sources” in Rise and Kill First he writes, “the firsthand accounts that these men and women have given for this book — men and women who witnessed and participated in significant historical events — are in fact the only ones that exist outside the vaults of the defense establishment’s secret archives.” He also writes of his outsider status, “this book must be taken as a ‘foreign publication’ whose contents do not have any official Israeli confirmation.”

The push and pull between these two positions is evident in his ongoing assessments, across many different levels (strategic, tactical, legal, ethical, moral, religious, historical and more) of targeted killing. This dynamic is particularly evident in the section on the 2004 death of Yasser Arafat, an event about which Bergman says, “If I knew the answer to the question of what killed Yasser Arafat, I wouldn’t be able to write it here in this book, or even be able to write that I know the answer. The military censor in Israel forbids me from discussing this subject.”

Even so, there are limits to the outsider status. Rise and Kill First does not access the vantages, words and experiences of the very people, populations, organizations and even nations against whom these fatal attacks are directed.

Bergman zooms in close, layering detail on top of detail. Early in the book he quotes Meir Dagan: “Sometimes it’s most effective to kill the driver, and that’s that.” Much of the book is an up-close examination of instances of killing the driver. To achieve this Bergman paints a picture of people. His vivid illustrations of prime ministers, ministers of defense, chiefs of staff, soldiers, statesmen, operatives, agents, reactionaries, revolutionaries, hardliners and moderates color the page. In writing of so many people so strikingly he distinguishes his book from biography. Bergman also writes of moment-by-moment action. He explains an operation from start to finish even if not all aspects of each operation are included. In writing of the 2010 assassination of Mahmoud al-Mabhouh in Dubai, after explaining why earlier attempts were aborted, Bergman vividly runs through how each member of the team arrived in country, which isn’t something he invariably discusses.

This richly realized writing makes the book excerptable; indeed, the New York Times Magazine ran the story of “Israel’s Long-Running Attempts on Yasser Arafat” and Foreign Policy ran “How Israel Won a War But Paid a High Moral Price.” These two pieces complement each other to reveal the abiding strength of Rise and Kill First. Over the entire book Bergman unfurls specific examples of targeted killings within the longer story of how the practice took hold in the first place, what allowed it to continue, and the ways it was shaped by events even as it shaped events.

The limited timeframe of individual operations exists within a practice that stretches from the British occupation of Palestine through the Holocaust, the founding of Israel, the death of Israeli Olympic athletes in Munich, the rise of Fatah, the rise of Hezbollah, to today’s tensions with Iran and the US over the Iranian nuclear program. In covering all of these events, what led up to them, the events themselves and then their aftermath, Bergman’s book links together material that other books handle singly or separately. Taking the long view allows Bergman to make at least three crucial points about the intelligence apparatus in Israel: it is “adjacent to yet separate from the country’s democratic institutions”; it was not merely about “protecting Israel and its citizens but as a sentinel for world Jewry”; it is intimately, much more so than in the US, tied to operations, “special-operations units were under the direct control of the intelligence agencies Mossad and AMAN.” Bergman also writes of the many forms of fallout from extrajudicial killings. Dagan speaks of killing the driver, but Bergman notes, “As Israel would learn repeatedly in future years, it is very hard to predict how history will proceed after someone is shot in the head.”

In Rise and Kill First, enduring proceedings include tactical successes at the expense of strategic success, and a dismissal of dialogue, diplomacy and engagement. The murder of the Israeli athletes in Munich at the Olympic Games gave rise to retaliatory Mossad operations inside European countries, including Germany and Norway, at the direction of Prime Minister Golda Meir. Operation Spring of Youth went inside Beirut to kill PLO members involved in Munich. Mossad operatives in Norway and in Lebanon made mistakes, but these were ignored. Bergman writes, “nwavering faith in the armed forces and the belief that the three branches of the defense establishment . . . could save Israel from any danger whatsoever led the country’s leadership to feel that there was no pressing need to reach a diplomatic compromise with the Arabs.” In October 1973 Egypt and Syria attacked Israel on Yom Kippur. The outcome, was, “victory… at a heavy cost” of “more than 2,300 Israeli soldiers.” Specific, focused and short-term gains breed longer-term problems, a cycle of violence and escalations takes hold, which prompts leaders to fall back on the same tactics so that the cycle rotates again.

Bergman gives us a way to assess his work. In writing for 800 pages about “the secret history” he announces that visibility, achieved through sustained attention, are his benchmarks. In drawing a tight circle around Israel Bergman prompts us to widen our angle of view. Bergman himself is not particularly interested in the long history of political assassination or in uses of assassination outside of the Israeli context, but this is territory that other writers have covered in both book-length form and in the popular press.

High-profile examples of arranging meetings with God are in the news these days. Today state-sanctioned killings are most likely to call to mind the image of a bald Alexander Litvinenko in his hospital bed, the picturesque streets of Salisbury on which Sergei and Yulia Skripal collapsed after being poisoned or two young women in a Malaysian airport delivering VX nerve gas to Kim Jong-nam and even a shawl-clad Osama bin Laden in an upper-floor room with white walls. These targeted killings by countries as different as North Korea, Russia and the US make visible a reality that is usually kept out of sight, but we still can see it. Buzzfeed ran a series on Russian assassinations in the west, including in the US.

In the US context, targeted killings often involve UAVs. Reading Bergman it was hard not to think of David Sanger’s Confront and Conceal, an important book about, among other things, President Obama’s use of drone warfare. And while Bergman isn’t particularly interested in the development of technology or the shifting nature of warfare in light of emerging capabilities it’s clear that his account touches on issues that are important to others writing in and about the US including Rosa Brooks in How Everything Became War, Paul Scharre in Army of None, and Sharon Weinberger and Annie Jacobsen in their studies of DARPA, The Imagineers of War and The Pentagon’s Brain.

In writing in a detailed way about Israel, about its history and its intelligence operations not only does Bergman tell “the secret history,” but he gives us ways to enrich, illuminate and even advance conversations that are already underway.

Katherine Voyles lives, teaches, reads and writes in Seattle.