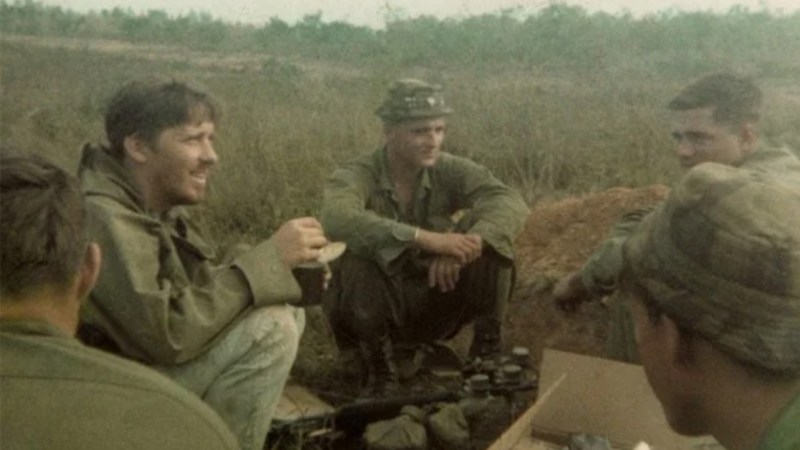

Documentary filmmaker Matthew Heineman has been covering conflicts for years, from the drug war in Cartel Land to the Syrian civil war in City of Ghosts. The Oscar-nominated director’s latest movie is Retrograde, which places him — and, thanks to his style, the viewer — in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province in the last year of the war. What unfolds is an at-times claustrophobic view of the effort to maintain control even as the situation collapses around the Afghan army and the Taliban close in.

Initially, the documentary is about a team of Green Berets deployed to Helmand and their work with the Afghan military. After President Joe Biden announces the United States’ withdrawal from the country, Heineman and his team stay, shifting their focus to Afghan Gen. Sami Sadat, who is charged with keeping Helmand Province from falling into Taliban hands.

Retrograde is immersive, with the filmmakers putting the viewer inside helicopters under fire, alongside Sadat on the front lines, and in the makeshift headquarters of the Green Berets as they go about purging their space of whatever they can’t take with them.

The film forgoes talking heads and most voiceovers, with only some contextual contemporaneous NPR stories playing over some scenes, often as interviews with Sadat or American officials discussing the state of the war. In most cases, Retrograde doesn’t identify the people on screen. As a result, it is both accessible to people who might not have followed the ins and outs of the war, and yet the people on screen provide a view of the war that has not often been heard or seen outside of those who took part in it.

The film begins and ends at Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport, before an ISIS suicide bomber killed more than 183 people, including 13 American service members. The filmmakers left the day before the attack, but the footage of the chaos at the airport, including at Abbey Gate, is visceral.

Retrograde is currently playing in select theaters ahead of its release on National Geographic on Dec. 8. Task & Purpose saw the new documentary at a festival screening and spoke with filmmaker Heineman this month about the process of making the documentary and what the final months of the war in Afghanistan were like.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Task & Purpose: How Retrograde starts and how it goes is a really well done journey, I wanted to get a sense from you how it started. You’ve said you guys were trying to talk with Green Berets and it was constantly evolving negotiation. What was the idea? Follow Green Berets in Afghanistan for the 20th year of the war?

Matthew Heineman: I think the original purpose of the film was to sort of do this holistic look at a deployment, both from the soldiers perspective and then also of the families back home. I wanted to do this sort of 360 look at what going to war looked like, and was like in the ‘20s. As time went on and it took years to get access to embed with the Green Berets and then Covid happened, it became clear that wow we could maybe tell the story of the end of the War in Afghanistan through the prism of this deployment. By the time our team actually deployed with them, wow it might actually be the last U.S. deployment, on the 20th anniversary of 9/11. That was what the original intent of the film became, which obviously changed as time went on.

Outside of General Sadat and the lead Green Beret [identified as “Chief Jack”], you don’t really have names in the movie. You have some titles, but not many names. Was that intentional, to leave most of these people nameless but recognizable?

In the film, every single frame and pixel was contemplated on and argued on. It definitely wasn’t an accident. Amongst the Green Berets no one really emerged as a sort of central character, that’s part of why, besides Col. Cheney who was in charge, we didn’t title anyone. The focus obviously shifted to Gen. Sadat, especially as the Green Berets left.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

One of the really striking parts is that scene on the balcony in the second half of the film. Gen. Sadat takes a phone call and leaves and you have his staff there, pondering that they’re losing the war. Had you heard that acknowledged before that point? What was it like hearing them say that?

I think that’s part of what the narrative tension of the film is, right? Metaphorically every neon sign was saying stop, give up, surrender, this is over. Gen. Sadat had this unwavering belief in himself and his men that maybe, just maybe if they held onto [the city of] Lashkar Gah, onto Helmand, southern Afghanistan, then they could keep the country together. He had this belief until the very end. Obviously, this film isn’t an attempt to dissect what went wrong, who’s at fault, what led us to this point, what’s going to come afterwards, there’s never an intent to do any of that. But surely, one of the big issues with why things went the way they went is enormous loss of morale amongst the Afghan army after the U.S. left. Part of Gen. Sadat’s job was to bolster, to boost the morale of his men and those he was recruiting. Part of why I love making docs this way, which is deeply intimate, personal, observational, apolitical, it’s all based on trust. That trust isn’t given, it’s earned. You have to continue to metaphorically renew your vows every week, every hour, every minute sometimes. That’s not just with him, it’s with all of the people around him.

The men who were working underneath him, we’d spent a fair amount of time with them, we weren’t strangers to them. So when Gen. Sadat walks in to take a phone call, they are comfortable with us staying behind on the porch with a camera. We don’t speak — my colleague Tim [Grucza] and I were both filming that — and we don’t speak Pashto or Dari so we didn’t exactly know what was happening. We could tell though, they were whispering, there were some sort of doubts. Didn’t know the periods or commas, but the page was quite clear in what they were saying.

Your style is immersive, letting them speak. But did you and your team have that sort of thought, those red flags, that things were going poorly in the war?

Oh I mean, not only could you see it first hand, it was reported on daily, both in Afghan and international media. This province fell, this province fell, this capital is surrounded. You just need to have a brain and two eyes and you could see that this was happening. Obviously part of the second act of the film is you feel the enemy, you feel the Taliban closing around us. In that governor’s compound where he’s holed up in Lashkar Gah, the bullets were distant, then they got closer, they got closer, then they got closer, then they’re flying over our heads. So the fight was getting closer and closer to the city. It was quite scary, honestly.

You chose to end the film at the evacuation at Hamid Karzai International Airport. I believe you have said you left the day before the attack on the airport. You were also working on The First Wave [his documentary about the Covid-19 pandemic]. Was there a point in filming prior to that where you thought, “this is it, we don’t need to go back and get more footage?”

No. We had sort of every piece of the puzzle of this final chapter. We had the U.S. military perspective, the Afghan military perspective. Seeing it all fall in real time, it felt irresponsible not to be there for the final moment. In mid August we were in touch with Gen. Sadat, we were planning to go back and film with him. Experts, pundits, military friends and advisors, they were saying it could be up to six months, could be two to three months [until Kabul fell]. We had no idea. By the time we got to Dubai to fly to Afghanistan, things were falling apart quite rapidly. We got on a plane to Kabul and as the plane descended into the valley the pilot got on the intercom and said “There’s a plane on the tarmac we can’t land.” We were so low our phones started to ping ping ping. We got news alerts that the Taliban had taken over Kabul and the plane on the tarmac was President [Ashraf Ghani]. The pilot was too scared to land.

We flew back to Dubai, and I felt like it was the greatest failure of my entire career. We spent eight months building this story and we’re sitting on an airport fucking hotel hundreds of miles away on this tragic historic day with our main character at the center of it, and we’re missing it. We basically spent every waking hour after that trying to get back into the country to tell this final part of the story. By the time we did, Gen. Sadat had been forced to flee. Once again we were left thinking what is the story we’re telling. We’re not the news, I’m not here to file a story to the BBC, to CNN, Vox, we’re there for a different purpose. With every failure comes opportunity with every door that closes, what this opened up was the ability to open up the metaphorical aperture of the film to see the civilian that Gen. Sadat had been fighting for, to see the civilians the Green Berets were fighting for, who are so often lost in the conversations around wars. These decisions around wars are often made by politicians in capitals far away, but those who are most affected are everyday civilians in those countries.

To open up and see this tragedy to see all of the civilians desperately trying to flee what they knew was about to happen, obviously a lot of false promises had been made, made the film what it was. I’m not sure it would be what it is without that. When we got to the airport we made this decision to leave the wire and go outside, not knowing if we’d get back inside.

We made this decision to leave the wire A) because we didn’t want to get stuck at the airport B) to see what the city felt like under Taliban rule and C) to see the civilian perspective. A lot of my military friends said I was an idiot. One of the first things we filmed was the Taliban meeting. We had heard through some colleagues they were meeting in the polytechnic institute. It was surreal sitting on stage with them after years spend reading about the Taliban, hearing about the Taliban, and the previous several months being shot at by the Taliban.

That night we ended up going to what they called the “gas station gate” and it was the opening scene of the movie. Right as we came onto the scene it was chaos. There was gunfire everywhere, civilians, cars honking, there was a traffic jam, absolute sort of anarchy. This long-haired guy grabbed me. I thought it was the Taliban. He dragged me through this crowd of people and through this gate. I’m not an expert in military tactics but it definitely felt like a situation I didn’t want to be in. I thought I was going to get kidnapped or beaten or worse, I didn’t know what was going to happen. It was this sort of movie moment, he leaves me in this dark alley and says “wait here.” Again, millions of thoughts are racing through my head. Out from the shadows emerges this big, burly chested American. He says “What are you doing? We see you out there filming you’re an idiot you’re going to get yourself killed. You’re an idiot. I explained to him, I said “Look I’m a filmmaker. We’ve been filming here for months, we were embedded with a Green Beret team in Helmand. I’m out there doing my job trying to tell this story.” What went from an antagonistic conversation became a cordial one. He said “Look here’s my number, we’re going to close this gate tomorrow, and if you want to get on a plane and get out, come back.” He called me the next day and said we’re closing the gate in 30 minutes. We were on the opposite side of town, traffic was crazy, but we got there. Honestly one of the things I’m most proud of, is we were able to get our Afghan field producers and translators who had also worked with the Green Berets and their families through that gate, in a very chaotic environment. And they’re now safely here in the U.S.

Just before the end of the film, you cut back to the Green Berets who are trying to get their allies out, and to Gen. Sadat who is also working on that. You sort of set that thread up. The film ends where it ends at the airport, but I’m curious what’s come of that. You’ve seen reports about Russia trying to hire Afghan commandos, they’re making movies about soldiers trying to get Afghan allies out.

Two quick answers. Being at the Abbey Gate was definitely the most emotional life of my entire career. Thousands of civilians, American partners, NATO partners, were crammed like sardines in a four-foot sewage ditch as 18-year-old Marines who weren’t even alive when the Twin Towers fell, making this impossible Sophie’s choice of who to let in, who not to let in, as the Taliban was watching us at gunpoint 100 yards away. And all as ISIS was circling around us with suicide vests waiting to attack — which happened 12 hours later in the very spot I was filming in. So surreal, all I could think about was “what have we done?” Obviously that was the end of that chapter, the tragedy of Afghanistan has continued. Col. Cheney, who was head of the Green Berets and featured in the film, he’s now retired and working full time on trying to get our Afghan partners out of the country who are still stuck there. Obviously there are thousands of our partners still stuck in Afghanistan, living in fear, some of whom are being hunted by the Taliban.

I have many many many hopes for this film, dreams for this film. One is, you know, the war in Ukraine is obviously incredibly important but it’s usurped so much oxygen in the international news media, I hope this film reinvigorates a conversation around the war in Afghanistan and this country we left behind. And especially our Afghan partners who worked alongside us and are living in danger. Some of whom are actively being hunted by the Taliban as I speak to you. I hope the film can help turn attention to those evacuation efforts, among many other things.

Retrograde is now playing in select theaters. It airs on National Geographic Dec. 8 and streams on Disney+ and Hulu Dec. 11.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Why the Air Force sometimes uses explosives to get B-52 bomber engines running

- Navy SEAL convicted for death of Green Beret Logan Melgar has 10-year sentence ‘set aside’

- Navy test squadron commander relieved for DUI after just 8 months on the job

- Russian-made missile strikes NATO member Poland

- The US is sending Avenger air defense systems to Ukraine to keep the skies free of Russian aircraft

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.