SARASOTA, Fla. — What happened to 26-year-old Icarus Randolph sounds like the rehash of a tired script: the Fourth of July in an African-American neighborhood, a call for assistance, white cops respond, tensions escalate in the front yard, gunfire erupts as the entire family recoils in horror and another young black man gets wheeled on a gurney to the coroner’s office.

This one occurred in Wichita, Kansas, on Independence Day, 2014. But the incident may well exceed the scope of a #blacklivesmatter scenario.

“We don’t think it was racial, but we don’t know what that cop may have seen when my brother came out of the house,” says Elisa Allen of Wichita. “My brother had that 1,000-yard stare, like he was somewhere else. I wish I had grabbed him and hugged him and he might still be alive today.”

Maybe the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were in that 1,000-yard distance. Maybe he was back in the Camp Pendleton brig, waiting in disbelief to be drummed out of the Marine Corps on an other-than-honorable discharge for getting busted for marijuana.

To hear his sister tell it, her little brother had never recovered from the stigma of being treated like a criminal by the military. Insisting he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, the former Marine had appealed for a status upgrade before being shot to death in Kansas.

The fate of Randolph and others like him is now at the heart of a class-action lawsuit aiming to erase the blight of “bad paper” discharges against post-9/11 veterans diagnosed for PTSD, traumatic brain injury and associated service-connected issues. And in a ruling that could ultimately impact hundreds of thousands of veterans, a federal judge has rejected the Navy’s motion to throw the litigation out of court.

In New Haven, Connecticut, on Nov. 7, U.S. District Judge Charles Haight Jr., gave the green light to lead plaintiff and Iraq war veteran Tyson Manker to proceed with discovery actions against Navy Secretary Richard Spencer.

Ejected from the Marine Corps in 2003 with an other than honorable discharge for marijuana use, Manker is charging the Navy with an institutional bias against sailors and Marines struggling with the largely unseen traumas of duty.

“Essentially, the rule that I want to come from this case is, if you have a PTSD diagnosis or something like (traumatic brain injury) and you apply for a discharge upgrade, it’s automatic,” says Manker, whose story was included in a 2018 Herald-Tribune special report, “Warriors Rise Up.”

“There should be no discretion from the board, from bureaucrats, to overrule the decision of a private doctor or a VA doctor. And I think that’s where we’re headed.”

One-third of those who served?

The litigation, Manker v. Spencer, is supported by the National Veterans Council for Legal Redress and the Yale Law School Veterans Legal Services Clinic.

The Yale students are arguing that nearly a third of the 2 million Americans who’ve served in Afghanistan and Iraq came home mentally or emotionally impaired by the experience.

If the suit prevails, Manker says Congress should codify any new standards into the Uniform Code of Military Justice, which could extend protections to veterans beyond the boundaries of the 9/11 generation.

“I’m elated for Tyson. He deserves this,” says Joanne Mills of Sarasota. “And I want Peter’s name cleared — he deserves it, too. This has been a nightmare for 40 years.”

Mills’ first husband, Vietnam-era Navy veteran Peter MacRoberts, committed suicide a week before Christmas in 1978, shortly after the Navy denied his third appeal for a status upgrade. She says her troubled husband never recovered from being branded as an “undesirable” after being arrested in 1969 for drugs, including a $10 bag of marijuana.

Class-action suits are difficult to win, but there is a precedent concerning the Army. In 1979, some 10,000 soldiers had their OTH discharges automatically upgraded after a federal court ruled that drug urinalysis results used to expel them had been illegally employed.

In 2017, Yale students filed a class-action complaint against the Army Discharge Review Board for perceived biases against soldiers with PTSD. Like the Manker suit, Kennedy v. Esper has also survived a motion to dismiss.

Bad paper, according to USMC veteran and student adviser Todd Mihill at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School, is “the equivalent of either a misdemeanor or felony conviction for substance abuse” on a veteran’s record.

In the civilian-sector job market, that military black mark “seems to tilt the playing field decidedly in favor of those who have not served,” Mihill added, and it may “preclude a transitioning service member from acquiring gainful employment.”

‘Reaching fair and consistent results’

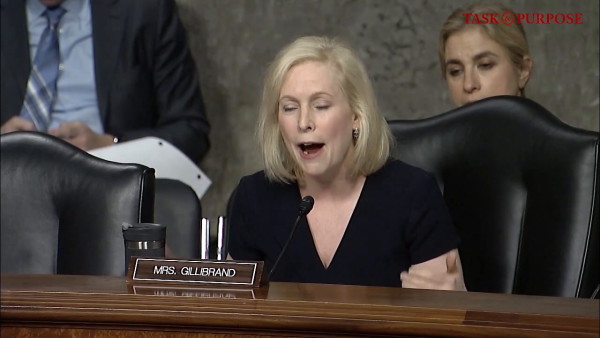

Noting how discharge review boards had been rejecting more than 95 percent of veteran upgrade requests since the turn of the century, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel in 2014 instructed the military to give “liberal consideration” to petitions involving PTSD, with the intent of “reaching fair and consistent results.”

Records disclosed in 2016 by the Freedom of Information Act indicated that applications for PTSD/TBI-related upgrades in the Army subsequently rose 45 percent, with the Air Force nudging up 37 percent. The Navy, however, granted upgrades to just 15 percent of the applicants. Its rejection of Manker’s 2016 application prompted him to go to court.

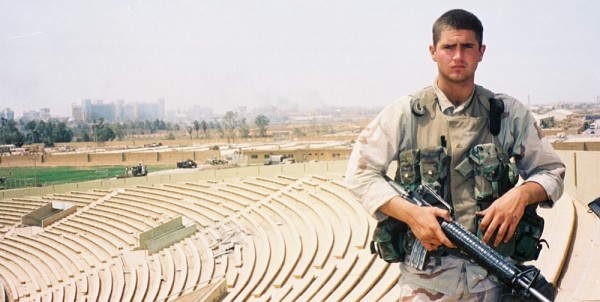

His unit had gone into Iraq with the initial invasion force in 2003. Its performance under fire in Baghdad and Karbala earned it the Presidential Unit Citation; Manker, at age 21, was promoted to corporal. But by December, he had been bounced out of the Marines with an OTH.

On the front end of a 30-day leave to the States, Manker and two junior Marines blew off steam by smoking marijuana. Although his urinalysis turned up clean — he smoked only once — one of his buddies flunked the test and rolled on Manker. He confessed during a lengthy interrogation that threatened him with 50 years in prison.

The OTH cost him his G.I. Bill, his pension, a $50,000 signing bonus, his rank (he was demoted to lance corporal) and a $1,500 fine. Despite the nightmares and hypervigilance, Manker and his unit all declined Deployment Health Assessment Assistance before leaving Iraq after being informed that such an appeal for help would automatically delay their trips home. He says the group was subsequently given a clean bill of mental health.

A doctor diagnosed Manker with PTSD within months of his leaving the service. He was referred to VA care, but his severance conditions made him ineligible. Manker went on to earn a law degree and is now a practicing attorney in Washington, D.C.

After a re-evaluation in 2017, the Illinois native finally qualified for VA assistance with an “other than dishonorable” upgrade. Citing multiple service commendations earned in Iraq, however, Manker calls his current status an unacceptable half measure. Smoking marijuana, he says, was his attempt to mitigate PTSD induced by his service.

PTSD wasn’t even on the books when Peter MacRoberts hanged himself. The American Psychiatric Association accepted it as a diagnosis two years later, in 1980. Manker says MacRoberts’ issues should have qualified him for an upgrade under Hagel’s “liberal consideration” directive, and he vows to help Mills clear her husband’s name.

“Peter served his country honorably for nearly three years, and he should get credit for that,” says Mills, who has been grinding through the appeals paperwork with an assist from the Disabled American Veterans. “His grandchildren will never know their grandfather, but I want them to know he was a good man.”

Twenty per day

Veterans are killing themselves more than 20 times a day in the new century, and checking out was definitely on Icarus Randolph’s mind in 2013 when he first attempted to get a status upgrade from the Navy.

“I am mostly anxious, nervous, depressed, stressed, angry, thoughts of suicide, feelings of self-hate,” he wrote, hoping to qualify for professional help from the VA. Randolph noted he had not “adjust(ed) well to civilian life and applied that ‘death before dishonor’ mindset. Sometimes I feel as if I need to keep those ways of thinking in my mind.”

Elisa Allen says her “sweet brother” was just 17 when he joined the Marines after high school graduation in 2007. He came home “a changed man” following his 2010 OTH discharge for marijuana, feeling “really lost, alone and ashamed.” His presence was fleeting, and he preferred to sleep on relatives’ floors rather than on couches or beds.

Randolph was never violent, says Allen, and he never talked about what he saw or did overseas. “I think he wanted to shield us from all that.” Unable to hold a job, “making really bad choices,” he began drinking heavily, and experienced “mental lapses” that resulted in hospitalization and run-ins with the law.

In 2014, with Independence Day fireworks popping and snapping across the neighborhood, family members summoned police after Icarus began speaking disjointedly “as if speaking to God and the trees,” according to the family. The encounter ended in the yard when an officer, feeling threatened, shot Randolph to death at close range. A knife was found near the body.

Eight relatives, including Allen’s three children, watched him die. She says a daughter, once an honor student, has been expelled from school with emotional problems. She says her son is afraid of people in uniforms.

“My brother still doesn’t have a headstone,” Elisa Allen adds. “My sister and I had to pawn everything to pay for the bulk of his services because we didn’t have any insurance.”

The city declined to prosecute the officer. The family continues to appeal.

On Jan. 11, 2016, Randolph’s survivors heard back from the Navy Discharge Review Board. “After careful consideration of all the evidence,” wrote the panelists, “the board felt that the subject’s PTSD should have mitigated the misconduct he committed since it outweighed the severity of the misconduct.”

The Navy recommended a general discharge under honorable conditions for the late Icarus Randolph. The final decision is still pending.

———

©2019 Sarasota Herald-Tribune, Fla. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.