In his Iraq War memoir Eat the Apple, Marine infantry veteran Matt Young offers readers a meditation on grunt life and war that’s crass, reflective, candid, and self-deprecating.

Inspired by Young’s three pumps to Iraq between 2005 and 2009, the memoir provides an alternative to the mainstream narrative surrounding America’s men and women at war. Unlike those tried and tested war stories that’ll get you a free beer and a hearty “thank you for your service” from patriotic civilians, the stories in Eat the Apple are likely to earn you a disgusted side-eye and a not-so-polite request that you leave the bar.

Related: ‘Eat The Apple’ Is The Belligerent, Unflinchingly Honest Iraq War Memoir We Needed »

Task & Purpose had a chance to chat with Young about belligerent ex-Marine shit: playing hot-potato with a piss-filled water bottle that has an MRE heater stuffed inside; the boot uniform of the day; how it’s kind of fucked up that we can’t talk honestly about why we wanted to go to war; and angry screeds by that one Facebook veteran who wants you to know he qual’d with iron sights on the range. (Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.)

Task & Purpose: I’m familiar with the saying “Eat the apple. Fuck the Corps,” but why did you choose it for the title?

Matt Young: I kind of like the meaning behind it, which is kind of like: Take your enlistment, your four years, or whatever you’re doing in your time there, and really embrace it and digest it; then when it’s done, toss it and move on. And I just kind of like the irreverence of it. I think that’s how a lot of infantry Marines and four-year enlisters end up feeling. There’s a lot of anger and being disgruntled at the Corps. I think that saying encompasses a broad feeling amongst grunts.

T&P;: What reactions have you gotten from other Marines or guys you served with?

MY: I’ve had a bunch of vets reach out to me and tell me the honesty of it is helping them. That’s better than any praise I’ve gotten, because it feels like it’s having an individual impact on people, so that’s pretty awesome. But I did get the crusty old-man veterans who want me to be taken back into the military and court martialed or thrown into the brig, because they’ve got this particular image of the military that I’ve upset. I talk a lot about manhood and masculinity in the book, and when you start to touch that subject, it gets it going with a lot of guys, especially older men. That’s who I’ve gotten a lot of flak from.

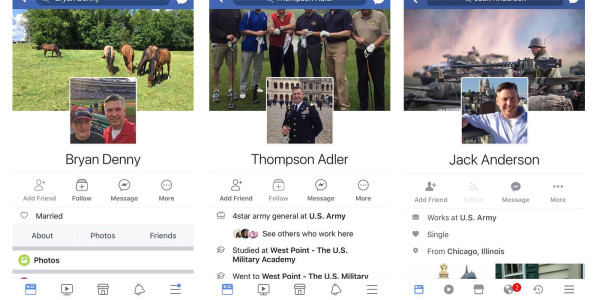

T&P;: I’m not surprised to hear that the “Old Corps” guys took issue with it — the ones who are always commenting that “back in my day we shot with iron sights.”

MY: Exactly, yeah. I don’t know why, but it feels like some older vets don’t want anyone to change their perception or how people perceive them. What, people aren’t going to offer you drinks in bars anymore because I wrote a book? Get out of here.

If that’s the reason you want to celebrate your service, for one, you probably need to reevaluate how you think about what you did, and you need to make room for other people’s stories. You can’t just have special operators running in and shooting Osama Bin Laden. There are other stories to be told.

None

T&P;: Do you think that veterans and probably Americans at large are honest about the actual reasons people join the military or want to go to war?

MY: I think getting at a more detailed explanation for why people join and what their motivations are behind it can help us understand — that’s where the divide starts between civilians and the military.

You have this assumption that you’re joining the military because you’re patriotic, because you want to go defend freedom. But I never felt by going to Iraq I was defending freedom. I think by the time we got there and you see how bombed out and destroyed that country was: In what way is Iraq a danger to the U.S. right now? There’s no possible way I’m defending someone’s freedom in the middle of America by going to Iraq and handing out bags of rice or going on snatch-and-grabs in the middle of the night.

T&P;: In the book, you talk about this idea of coming of age at war and wanting to be the guy with the thousand yard stare who can answer that question, “what’s it like to kill someone?” Why is it important to pull back the curtain and explain that maybe people don’t just join up to fight terrorists or defend freedom?

MY: Giving people that narrative that this is who you are, this is who you’re supposed to be, this is how you’re supposed to act when you come home, it keeps people at arm’s distance. When you’re coming back from war and people are buying you drinks in bars and telling you “Thank you for your service and for protecting our freedom,” you start to believe that narative, and you kind of overlay it onto your own, and your own motivations become twisted. And it becomes really hard, because society wants you to be a certain way, and you feel you have to be. And that’s really tough; at least, it was for me as a young man.

T&P;: Did you ever pull any pranks, or just do stupid shit while deployed?

MY: (Laughs.) When we were right outside of Fallujah, we were living in fighting holes that we’d dug into the side of a hill. It was super boring. We would take MRE heaters and we’d put ’em in bottles, and somebody would pee in the bottle. And we’d throw them back and forth between the fighting holes in the worst game of hot potato ever created — until the piss bottle would explode.

I think that’s how humor works at war. Everything else was so horrible that anything you can do that distracts becomes funny, especially if you’re willing to self-deprecate…

It disrupts that narrative. You’re not the SEAL Team Six guy: You’re the jackass with the helmet that’s too big, the flak jacket that has too much shit on it, and you’re trying to kick in a door and you can’t because it opens out, and somebody comes up and opens it then goes in without you because you’re a dumbass and you’re trying to open a door wrong.

T&P;: What’s the dumbest, bootest thing you ever did?

MY: I have two tattoos. One says “USMC” on my forearm, and I have “Devil Dog” written on my other forearm in old English writing, and that lasted in the fleet for about two months before I got ragged on so hard that I got it covered up with a half sleeve.

And then there’s, like, the backpacks and stuff. Buying a supermoto go bag and going down to Oceanside for the weekend.

T&P;: Right, right. Like your tucked-in polo or undershirt and sneakers. The boot uniform.

MY: Yeah, with my awesome high-and-tight.

T&P;: And the dog tags, for sure, like everyone doesn’t already fucking know you’re a Marine.

MY: I once saw somebody put their dog tags in their sneakers. That was probably one of the most boot things I saw: a pair of Converse All-Stars with a dog tag on the left lower lace. I was like oh, Jesus.

T&P;: That’s sounds like a photo on Terminal Lance.

MY: It’s like, who hurt you?

WATCH NEXT: