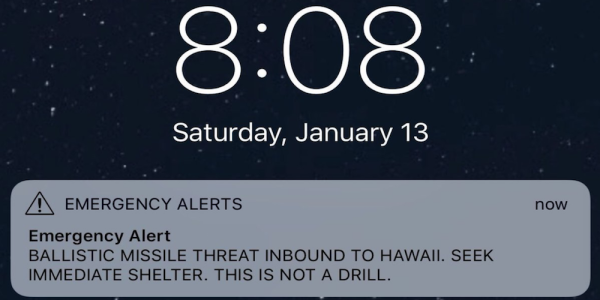

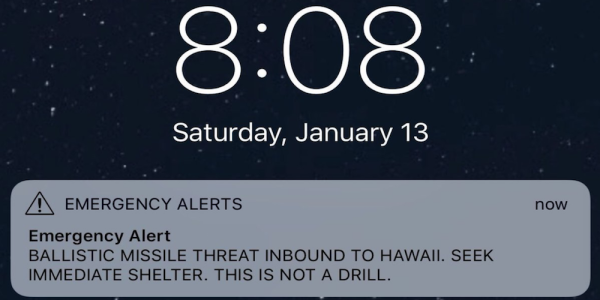

The Hawaii Emergency Management Agency worker who triggered panic by sending a false ballistic missile alert to phones across the state on Jan. 13 believed the state was actually under attack, according to a preliminary investigation released today by the Federal Communications Commission.

Gov. David Ige and HI-EMA officials, in several public explanations on the false alarm, have never revealed that the agency “warning officer” actually thought a missile attack was imminent, instead saying that he pushed the “wrong button” or selected the wrong option from a drop-down computer menu.

FCC Chairman Ajit Pai and staff discussed the Jan. 13 event in a preliminary report during this morning’s commission meeting in Washington, D.C. While a final report has yet to be issued, their initial probe has revealed that poor planning, inadequate technology and a series of errors from multiple people contributed to and exacerbated the button pusher’s mistake.

According to the FCC findings presented in Washington today, a shift supervisor initiated a drill of the missile alert system by pretending to be U.S. Pacific Command and played a recorded message over the phone.

“The recording began by saying “exercise, exercise, exercise,” language that is consistent with the beginning of the script for the drill,” according to the FCC investigator. “After that, however, the recording did not follow the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency’s standard operating procedures for this drill. Instead, the recording included language scripted for use in an Emergency Alert System message for an actual live ballistic missile alert. It thus included the sentence “this is not a drill.” The recording ended by saying again, “exercise, exercise, exercise.”

“According to a written statement from the day shift warning officer who initiated the alert, as relayed to the Bureau by the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency, the day shift warning officer heard ‘this is not a drill’ but did not hear ‘exercise, exercise, exercise,’ ” the FCC reported. “According to the written statement, this day shift warning officer therefore believed that the missile threat was real. At 8:07 a.m., this officer responded by transmitting a live incoming ballistic missile alert to the state of Hawaii.”

The male warning officer, HI-EMA officials revealed last week, is not cooperating with either the FCC or internal investigations into the Jan. 13 event.

FCC Report by Honolulu Star-Advertiser on Scribd

Pai said in a statement, “In my view, here are the two most troubling things that our investigation has found so far: (1) Hawaii’s Emergency Management Agency didn’t have reasonable safeguards in place to prevent human error from resulting in the transmission of a false alert; and (2) Hawaii’s Emergency Management Agency didn’t have a plan for what to do if a false alert was transmitted.”

“Every state and local government that originates alerts needs to learn from these mistakes,” Pai continued. “Each should ensure that it has adequate safeguards in place to prevent the transmission of false alerts, and each should have a plan in place for how to immediately correct a false alert.”

“The public needs to be able to trust that when the government issues an emergency alert, it is indeed a credible alert. Otherwise, people won’t take alerts seriously and respond appropriately when a real emergency strikes and lives are on the line,” Pai said.

Pai and FCC staff discussed the Jan. 13 event and the preliminary report during this morning’s open commission meeting in Washington. While a final report has yet to be issued, so far, their probe has revealed that poor planning, inadequate technology and a series of errors from multiple people contributed to and exacerbated the button pusher’s mistake.

FCC investigators identified the following key errors:

- Miscommunication between the HI-EMA’s midnight shift supervisor and the day shift supervisor resulted in a drill being run without adequate supervision.

- The midnight shift supervisor started the drill by playing a recording that deviated from the agency’s drill script because it incorrectly included the words, “This is not a drill.”

- The day shift warning officer who triggered the false alarm said in his written report that he failed to recognize the exercise was a drill because he had not heard the script words, “exercise, exercise, exercise,” although other warning officers had.

- When the false alarm was happening, HI-EMA did not have any procedures that required warning officers to double check with a colleague before double-clicking a live-alert prompt, which did not offer the warning officer an opportunity to review the text.

- The state conducted an atypical number of “no-notice drills,” increasing the potential for error.

- Alert-origination software didn’t differentiate between tests and live alerts and wasn’t hosted on separate domains or applications.

- HI-EMA’s reliance on stored templates made it too easy for the warning officer to click through the alert origination without sufficient focus.

- HI-EMA had not anticipated the possibility of issuing a false alert and wasn’t prepared to issue a correction.

- HI-EMA was overwhelmed by calls, some of which didn’t get through.

- Gov. David Ige delayed sending out social media notification because he forgot his Twitter password.

The FCC said it was pleased that the agency already has taken steps to ensure that a similar incident never happens again, but said “there is more work to be done.”

At today’s hearing in Washington, FCC Commissioner Mignon Clyburn said the false ballistic missile alert in Hawaii should be a “wake up call for all stakeholders involved in emergency communications.”

“We cannot simply dismiss this as being an inadvertent mistake that only public officials and Hawaii need to address,” Clyburn said. “This incident should serve as a catalyst to review their emergency alert process. Every community should be doing more to prevent an issuance of a false alert.”

Clyburn said if and when a false alert is ever sent again, “the technical capability to immediately send a correction should be in place and the protocols on how to go about that should be clearly defined.”

———

©2018 The Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

WATCH NEXT: