More than seven decades ago, Aaron Bank had an idea. He decided that after years killing Nazis, almost leading a manhunt for Hitler, and then working alongside Ho Chi Min to liberate Vietnam from imperial Japan, the United States Army needed some special fighters. A force versed in irregular warfare, who could mess up an enemy from behind their lines, working with local resistance. A special forces, if you will. Seventy years ago Aaron Bank got his wish.

June 19 is celebrated as Juneteenth, now a federally recognized holiday. June 19 is also the 70th anniversary of the creation of the U.S. Army Special Forces, better known as the Green Berets. And since Father’s Day also falls today, it feels apt to honor Col. Aaron Bank, who’s known as the “father of special forces.”

Bank was born in 1902 in New York City. He grew up working as a life guard, where work took him from New York to France and the Bahamas. At 39 he joined the Army after Pearl Harbor, with his level of fitness helping him overcome doubts about his age. He joined the CIA’s precursor, the Office of Strategic Services, immediately going into work on sabotage, guerilla warfare and recruiting partisans to help fight the Nazis in Europe. His work peaked when he was a part of Operation Iron Cross, a plan for the OSS and Bank to, using a cadre of German Jews, communists and defectors, parachute into the German-Austrian border and capture or kill Adolf Hitler if he fled Berlin. Hitler hid in a bunker and never left the city, leading to the cancellation of the operation and denying Bank of what surely would have been a movie-inspiring military action. After the war in Europe ended he found himself in southeast Asia and supported Ho Chi Minh as the head of a future coalition government. American policy went against Bank’s recommendations. Still in the service, he pushed for a formal Army force dedicated to the kind of irregular warfare Bank had made his trade.

This month, Rep. Richard Hudson (R-NC) introduced a motion in the House of Representatives to honor both the Special Forces and Aaron Bank himself, who retired as a colonel. Rep. Hudson’s resolution notes that the Green Berets “encouraged the incorporation of principles of force multiplication into the military doctrine of the United States and paved the way for the revitalization of special operations forces in the Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps” and “helped revolutionize the conduct of modern warfare.” It’s hard not to see how.

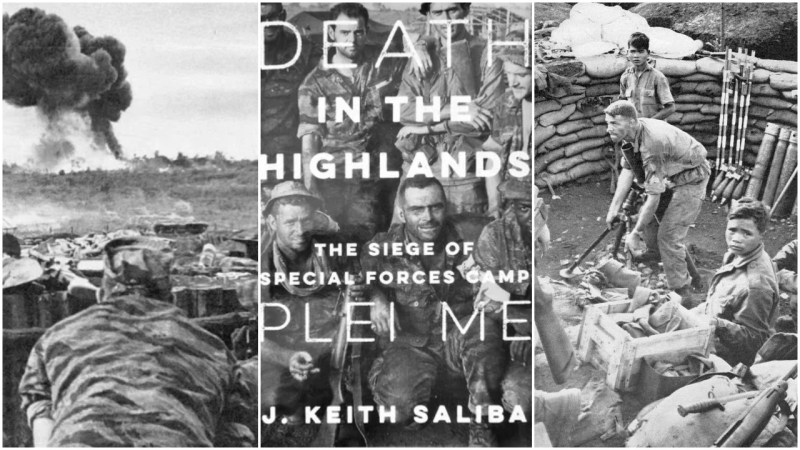

Since the creation of the Army Special Forces in 1952, the force has been an instrumental tool in the Army. Originally just one group, the 10th Special Forces Group, it expanded into several units. They were deployed to South Vietnam as advisors for that country’s army and were a part of U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, an unconventional warfare group fighting against the forces of Bank’s former compatriot Ho Chi Minh. Missions also included covert actions in Laos and Cambodia. Other deployments included several conflicts in Latin America and the Persian Gulf War. Special Forces were part of the initial U.S. assault on the Taliban in fall 2001 in Afghanistan.

As the premiere special operations forces in the public for years, the Green Berets got a lot of attention. In the world of fiction, there was a less than stellar film about them starring John Wayne. Col. Kurtz and Capt. Willard both counted themselves among the ranks in Apocalypse Now.

In the 21st century they’ve been somewhat eclipsed in the public eye by various “tier one” special operations forces such as Delta Force and Navy SEALs, but they remain a key part of the military, deployed in Africa, the Middle East and elsewhere doing the irregular warfare they have been doing for the last seven decades.

Rep Hudson’s resolution is, as of press time, in the hands of the House’s Armed Services Committee.

As for Bank himself, he had another major contribution after leaving the Army in 1958. Relocating to California, he became concerned with what he saw as poor security at nuclear power plants. Working with the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists he shed light on the concerns and helped spur plants to overhaul how they protected nuclear installations. He died in 2004 at the age of 101. Not bad for a guy who was robbed of the chance to kill Hitler.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- US Navy aircraft carriers may be useless in a war with China

- A helicopter flown in Afghanistan is now a military couple’s camper

- We salute the Navy captain who took 700 sailors to see ‘Top Gun: Maverick’

- These photos capture what life is really like in the military

- Hollywood has spent $16 million training Chris Pratt for war

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.