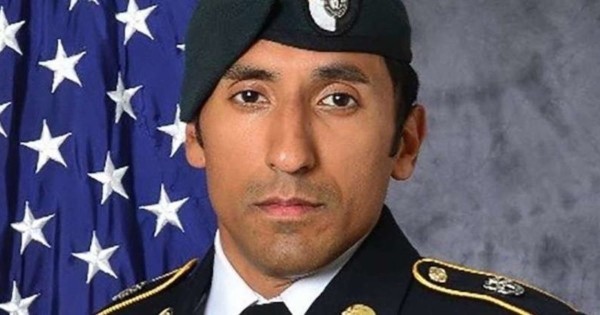

I didn’t know Dewey Smith. For me, the memories of his face are limited to the friendly but frozen pictures that were featured in the news articles about his death. But when you work in a community as small as ours, each death sends out ripples, and Dewey’s premature demise made waves. Now, thirteen years later, after many long years of hard work, I can finally say I may have found a solution that could have saved him. May. It could still fail. But I’m going to keep working.

This story is about what it’s like for the nerd folk like me — civilian military employees who work desk jobs — after the death in the field of someone with a more hands-on type of role, like operator, diver, or even Air Force officer. It’s how we respond, with “we” meaning the desk jockeys, the sand crabs, the inside kids. It’s how we struggle quietly in our labs and in front of the sickly light of our computer monitors to prevent the next death using the lessons taught us by those we have already failed; those like Dewey Smith.

Smith was a U.S. Navy veteran who, after separating, found a way to carry on his love affair with the ocean at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, better known as NOAA. At this job, he spent a substantial amount of his time underwater. However, on May 5, 2009, the pressure waves from a nearby underwater jackhammer flipped through the settings of the electronics package of his breathing equipment and turned off the computer that was monitoring and controlling his supply of oxygen, without his knowledge or permission. He was using a specialized type of equipment called a mixed-gas rebreather, which recycles a diver’s breathing gas, injecting new oxygen to replace what the diver has already used up.

Dewey Smith was an extraordinarily experienced, skilled, and well-trained diver. Still, on that warm summer day in the Florida Keys, he breathed in the last remaining molecules of oxygen available to him, lost consciousness, and died. Nobody had done anything wrong, including him. Not really. Diving with a rebreather is the second most lethal activity in the world per hour, after BASE jumping. Once you remove from the statistics the weekend warriors who have heart attacks, about half of the all-too-frequent deaths are caused by the same phenomenon that killed Dewey: hypoxia, otherwise known as lack of oxygen. The divers almost never know what hit them, and the ocean rarely offers second chances.

Though I didn’t know Dewey Smith, I do know that he was a federal employee, diving on a government maintenance job in support of the U.S. Navy detachment I was working for at the time as a civil servant. His death sent out waves for all of us, impacting even those like me who’d heard about it from the safety of an office chair. It was a stunning reminder that no amount of skill can overcome a problematic equipment design. His funeral was in my town, far away from the Keys, so I offered his former coworkers access to my little run-down apartment so they could have hot showers and cold beer between their long drive and the start of the ceremony. As some of them cried on my cheap, lumpy futon in their black clothes, I stared at my hands awkwardly from a seat in the corner and found myself unsure what to do or say.

Math types like me aren’t known for our ability to find the right words in such moments. In fact, some would even say there are accurate stereotypes with respect to our lack of grace and our inability to find the correct verbiage, or gestures when faced with such raw human emotion. Most of us are more the type for action. Not action in the Michael Bay movie sense, but rather a slow, cautious, deliberate, detailed, careful action to improve what we see as broken machines; actions that might help prevent the untimely death of another diver.

It was my job to build diving equipment and ensure its safety, and I was just one more in the long line of engineer-scientists who had nothing to give that could have prevented more of these deaths from happening. So, it seemed like now it was my job to fix that. The next day, I began with a pencil and some scratch paper. I wanted to know if a pulse oximeter, the little glowing red finger clip medical patients put on when they have their vital signs taken, could be used to detect oxygen in the diver rather than in the equipment. They are designed to measure whether the body is transporting enough oxygen, but would they signal falling levels quickly enough to be useful to a diver?

I began the day after the funeral, but I wanted to tell this story now, thirteen years later, because just last month I finally hit one of the major milestones proving that such a safety device was functionally possible. A solution, thirteen years too late for Dewey and many others. Sadly, that is often the timeline of science.

In 2009 I already knew I was being sent back to graduate school by the Navy. I decided to kill two birds with one stone and told them to send me to Duke, where I could do this project, or I wasn’t interested in pursuing any fancy new degrees. Once I arrived on campus I wandered over to the hyperbaric chamber, where I started out as a volunteer, lending the researchers my body for the purposes of science. I got to know the staff there by letting them stab me with needles, and make me hypothermic, and on one particularly hilarious occasion, letting them try to give me Swimming Induced Pulmonary Edema (SIPE). Luckily, they failed. But, when I asked if they’d let me be a guest researcher, to try out an idea myself, they said yes.

The Navy gave me enough money to test my idea on ten volunteer test subjects by having them ride on a bicycle in the air. An Mk16 rebreather magically found its way to Duke – we won’t talk about how. I disabled the breathing loop, strapped some volunteers to the ceiling of a chamber with a safety harness, and these trusting souls (including the guy who would turn out to be my future husband) let me intentionally deprive them of oxygen while measuring the actual levels of oxygen in their blood with a pulse oximeter. The most common form of the “pulse ox” is the fingertip version, but that one would hardly be suitable for working divers who need to use their hands while underwater. So, the research team and I taped pulse oxes across our subjects’ foreheads. We added an experimental pulse ox from another university, along with a few more for good measure, instrumenting these poor trusting souls to hell and back in the hopes that at least one device would pick up something useful.

The pulse oximeters worked. The ones on the forehead, tucked gently beneath the mask skirts, provided the subjects with just under a minute of warning time. A minute is enough time to push a button. The push of a button is enough to save a diver’s life.

The project was nowhere near done. A device is not useful until you’ve proved it works in realistic working conditions, and the dark cold depths of the ocean with a diver struggling to use their hands for nimble tasks is hardly the same as a warm, comfortable, lab with safe test subjects pedaling a bike suspended in the air.

With heavy encouragement from my former detachment, from the divers who had seen these accidents firsthand, we scraped together more money to do another experiment. A bigger, badder, colder experiment inside a tank full of ice, with divers underwater — just like out in the real world, to make sure the effects of frigid water wouldn’t interfere with the useful way the oximeters measured blood flow in the skin. Unfortunately, however, after I got the money in hand, and after we were setting up and ready to go, my managers decided I would be more valuable pushing papers back on base in Florida. I decided then that if they cared more about paperwork than they did divers’ lives, it wasn’t the job for me. I quit. Again, luck was on my side, and Duke let me keep working on the project anyway.

Twenty-eight people let me put them, for the sake of the project and the science, into 68-degree water, wearing no thermal protection, only swim shorts and a scrub top. Often, our chillers couldn’t get the water cold enough and so there was still literal ice floating on the surface when the test subjects climbed in. We jammed gigantic needles into their wrists so we could take blood samples directly from their radial arteries, to prove our blood measurements were real. Then, once they were in the water, they breathed on a rig they knew had no oxygen in it, their wrists aching, their lips often blue from the cold, and still, they pedaled away until I asked them to stop. I pulled four volunteers from the water because I was concerned they were flirting with hypothermia. Thankfully, nobody actually passed out, although a few got close.

Yet they trusted me for all of it. These twenty-eight people, who will forever remain anonymous, put their bodies on the line to prove that my idea worked. Most of my volunteer subjects were and still are, scientists themselves. In science, there are those of us who publish the results and are allowed to write articles in Task & Purpose about what the projects are for. But the real heroes are the people who climb into the tank of ice, literal or proverbial, and give their bodies up to test out a concept that just might save lives.

Last month, my team and I finally published our paper. It was the second in the series, and it won’t be the last, because we have more problems to solve. Pulse oximeters don’t give divers a long warning time — we were a bit limited by the fact that I didn’t want anyone to pass out in the tank, so I pulled people out at a level that was still safe for them — but it’s at least 32 seconds. That’s long enough to hit a button. That’s long enough to signal for help. The concept, if it can be built into something rugged, simple, convenient, clean, and robust enough for divers to actually want to use, then it just might save someone’s life. That’s not a small if. But last month, finally, after 13 years of hammering away at the problem, we took another big step. We may finally have found a way to prevent a tragedy like Dewey Smith’s accident from happening, albeit more than a decade too late.

+++

Rachel Lance is a Ph.D. biomedical engineer and research faculty member at the Duke University Center for Hyperbaric Medicine & Environmental Physiology in Durham, NC, where she studies the effects of extreme environments such as explosions, undersea, and outer space on the human body. She is the author of In the Waves: My Quest to Solve the Mystery of a Civil War Submarine, and she is a gigantic nerd.