In its quest for Cold War military superiority, the United States detonated more than 1,000 nuclear weapons.

Government researchers blew up many of the bombs on the ground and others in ocean atolls. Yet as threats moved into space and concerns increased about fallout — soil and other material that’s sucked into a blast and becomes radioactive — the US exploded 210 of the terrifying devices high in the atmosphere.

Thousands of films of such blasts, made from 1945 through 1962, were analyzed and locked away in high-security vaults. It’s likely no one has seen the footage for decades.

But on March 14, after more than 55 years of collecting dust, the US declassified 750 of the high-speed films — and released dozens of the digital scans on YouTube. We first heard about the movies from the writer Sarah Zhang on Twitter.

A team of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory scientists led the rescue effort over the past five years. The films are made of nitrate cellulose and slowly decompose in the air while releasing a vinegar smell, according to an LLNL release.

“This is it. We got to this project just in time,” Greg Spriggs, a nuclear-weapons physicist at LLNL, said in a video about the digitization effort. “We know that these films are on the brink of decomposing, to the point where they will become useless.”

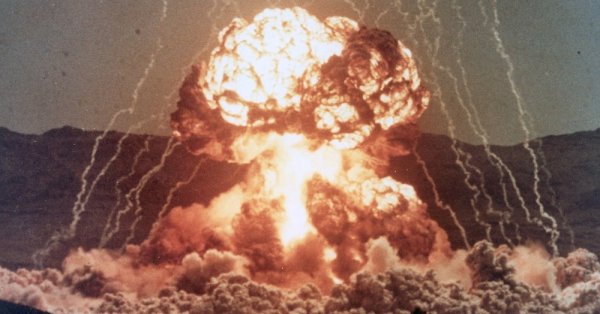

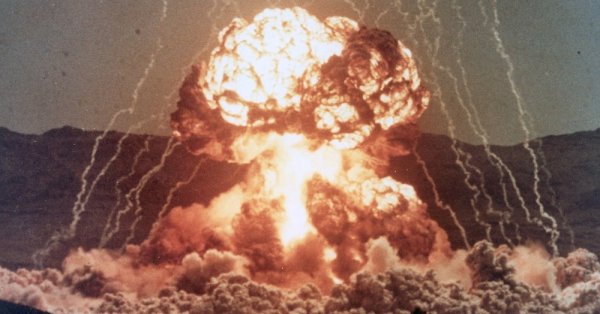

A still from one of LLNL’s newly declassified nuclear-weapons videos.Photo via LLNL/YouTube

The project isn’t just about shedding daylight on the advent of the nuclear age.

Spriggs said it’s also about getting lost data about high-altitude test blasts, which are prohibited around the world by the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty yet poorly understood. (The US, however, has yet to officially sign the treaty.)

“We don’t have any experimental data for modern weapons in the atmosphere,” he said. “The only data we have are the old tests, so it gets a little bit more complicated.”

The data may help researchers better understand the effects of nuclear explosions and manage the thousands of the weapons in the US’s stockpile.

“We found out that most of the data published was wrong,” Spriggs said. “We decided we need to re-scan and reanalyze all of the films.”

Film expert Jim Moye helps scan a nuclear-explosion film.Photo via LLNL/YouTube

About 10,000 of the movies were made, at speeds of thousands of frames per second to slow down fast-expanding explosions.

However, it took LLNL roughly five years to locate about 6,500 of the films, then digitally scan 4,200 of those. Spriggs said that, so far, the team has reanalyzed between 400 and 500 films.

Jim Moye, a rare-films expert and movie-industry veteran, helped scan and archive the footage.

“It is going to be gone at some point, and we don’t have forever to do this,” Moye said in the video.

The project is important to “help certify that the aging US nuclear deterrent remains safe, secure, and effective,” LLNL wrote in its YouTube video description.

Spriggs said the team was learning new details about the detonations — lessons he hopes to pass on to future generations.

“It’s just unbelievable how much energy’s released,” Spriggs said in the release. “We hope that we would never have to use a nuclear weapon ever again. I think that if we capture the history of this and show what the force of these weapons are and how much devastation they can wreak, then maybe people will be reluctant to use them.”

You can watch all of the newly declassified movies in LLNL’s YouTube playlist:

More from Business Insider:

- A forgotten war technology could safely power Earth for millions of years. Here’s why we aren’t using it

- 14,900 nukes: All the nations armed with atomic weapons and how many they have

- The 25 most powerful militaries in the world

- This is how Russian hackers broke into millions of Yahoo accounts without passwords, according to the FBI

- Former NSA director: America is ‘really good’ at stealing data from other countries