In 2005, this reporter at the age of 12 had never heard of the rapper Kanye West and he did not know much about the Gulf War. But when he heard West’s 2004 hit Jesus Walks in the trailer for Jarhead, he concluded that the song was very much a banger.

In the song, a choir sampled in the background lays down a marching cadence while repeating “Jesus walks with me” as West raps about his own religious conviction. The militant cadence and the divine lyrics seem to match perfectly with the awe-inspiring war images in Jarhead of Marines patrolling through an endless desert, oil wells burning and Air Force jets flying overhead.

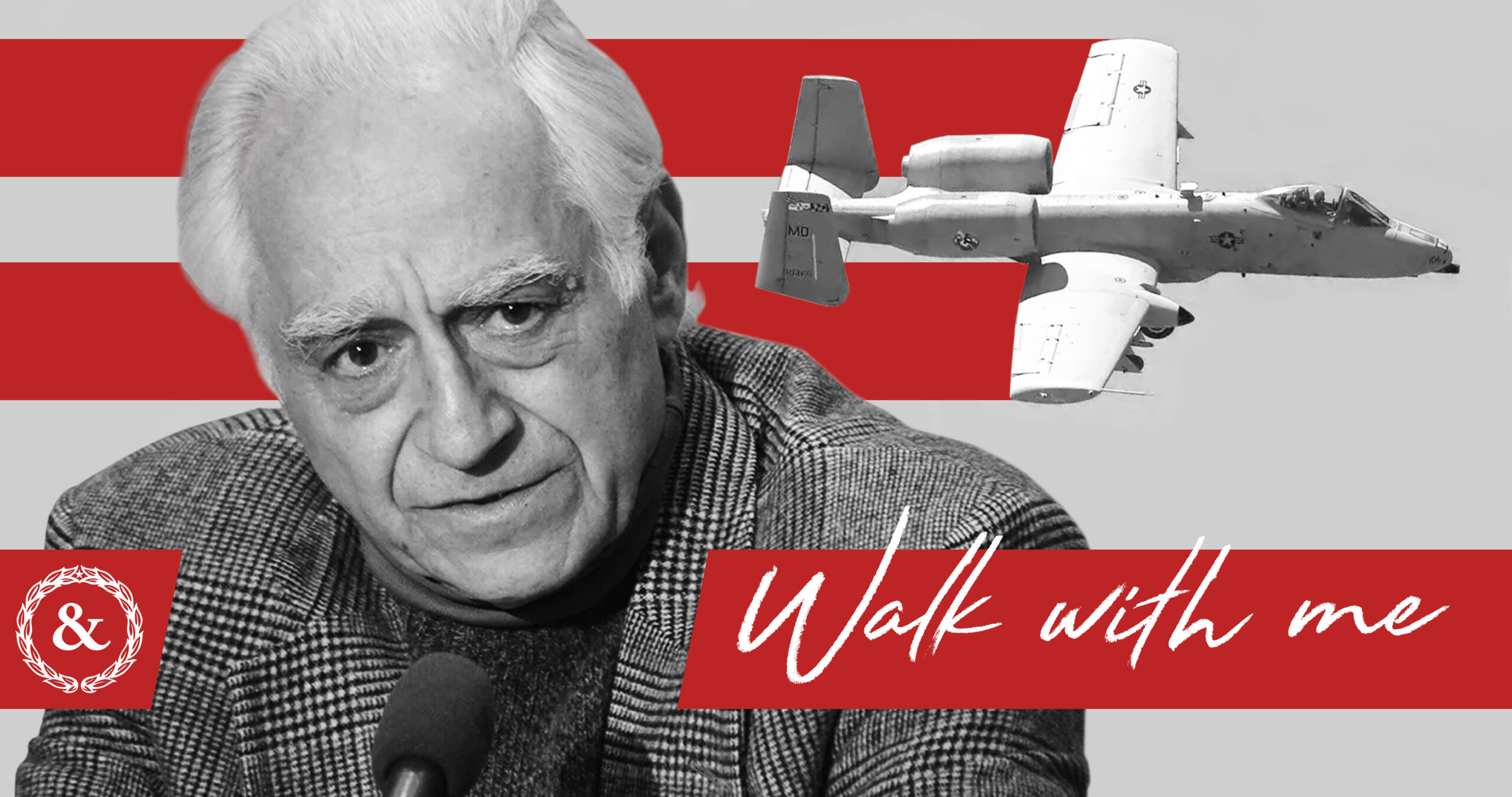

Turns out, the song and the movie trailer share much more than just tone and theme. In fact, the guy who heavily influenced the design of the Air Force A-10 Thunderbolt II (better known as the Warthog) jets flying overhead in the Jarhead trailer was the same guy who recorded the chorus of voices that makes Jesus Walks so hypnotic. You may have never heard of Pierre Sprey, but he was a remarkable individual who managed to make a mark on two very different scenes: the Pentagon and the music industry.

“He was one of the most detested people by the United States Air Force,” Tom Christie, a career Pentagon analyst, told the Washington Post in a 2021 obituary after Sprey had died of an apparent heart attack at the age of 83. “[H]e was challenging a lot of sacred programs and strategies.”

Born in France in 1937, Sprey and his Jewish parents moved to New York City in 1941, where he grew up going to jazz clubs and speaking German and French with his family while discussing classical music at the dinner table, according to the Post. Sprey entered Yale at the age of fifteen and studied engineering and French literature, then studied statistics and operational research at Cornell University, according to the 2002 book Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War, by Robert Coram.

By the age of 22, Sprey was running a statistical consulting shop for the aircraft manufacturer Grumman Aviation, and by 1966 he had taken a job at the Pentagon’s System Analysis office, where he was proving to be a major pain in the hind-quarters of the Air Force establishment.

Sprey wrote a report on behalf of then-Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara that roasted the Air Force’s strategy for fighting the Soviet Union in Europe. In its strategy, the Air Force hoped to stop Soviet forces from flooding across the continent by practicing “interdiction bombing,” where the branch would bomb bridges, railroads and industry. The Air Force had practiced interdiction bombing since World War II, before the service had even separated from the Army. But Sprey said the Air Force had no chance of stopping Soviet troops from invading Europe that way. Instead, he advocated for directly supporting ground troops through close air support and by providing enough air superiority so that close air support could be maintained.

“Air Force generals read Sprey’s report and became almost apoplectic,” Coram wrote. “Interdiction bombing was sacred doctrine. It was the rationale for separating the Air Force from the Army back in 1947.”

The analyst’s report also put two-thirds of the Air Force budget in peril, Coram wrote, but Sprey had the expertise and wit to back up his fighting words.

“He is a rarity, a civilian who can take on the Air Force on its own turf and prevail,” Coram wrote “Unlike many civilians who worked in the Pentagon, Sprey was not intimidated by rank; in fact he thought there was an inverse relationship between the number of stars on a man’s shoulder and his intelligence.”

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

Sprey soon started hanging around other pariahs like Col. John Boyd, whose theories on war changed aerial combat and led to the creation of the F-16 and F/A-18 fighter jets, which are still flown today by militaries around the world. Neither man was afraid to speak his mind: Sprey told a colonel in a packed conference room that the numbers in the colonel’s presentation were a lie, and when he was later asked to apologize, Sprey called the officer a “slimy creature,” who “oozed mendacity,” according to Coram. The analyst later played a key role in helping design the A-10, which has since become a legendary close air support platform renowned for its ability to take hits and dish them back out to anyone attacking friendly ground troops.

“The pilots love them,” Sprey said in 1999, according to The Washington Post. “Any of our jet fighters can be shot down by a .22-caliber rifle. But you can punch an A-10 full of holes and it will come home with sky showing through the wings.”

Together, Sprey, Boyd and several other independent thinkers formed what became known as the “Fighter Mafia,” a group of service members and civilians who argued that Air Force bureaucracy had become corrupt, with Air Force officials pushing over-complicated, expensive aircraft backed by poor test criteria and in support of useless objectives. Through the 1980s, the underground group managed to spread its ideas despite immense resistance from the Air Force establishment, in part because its underpinning philosophy applied to more than just air warfare.

“Not all simple, low-cost weapons work, but war-winning weapons are almost always simple,” Sprey said, according to the Post.

Helping design airplanes was not Sprey’s only passion. While visiting jazz clubs in New York City, the young Sprey began recording live music as a hobby, according to the Post. Years later, a Pentagon engineer showed him a high-end turntable, which inspired Sprey to take the machine apart and figure out how high-fidelity sound was made.

It began with a homemade recording system that used extremely thin wires and battery-powered microphones, which Sprey used to record a D.C.-based jazz singer named Shirley Horn. But Sprey also had a restored 1911 Steinway piano at his house in Upper Marlboro, Maryland. The piano captivated Horn, who said “P. baby, I want to do my next album on this piano and I want you to be my engineer,’” Sprey later recalled for the Post in 1996.

Sprey named his record label Mapleshade, after his house, where he recorded jazz and blues artists like the saxophonists Clifford Jordan and Hamiet Bluiett and pianists Walter Davis Jr., John Hicks and Larry Willis, according to the Post. When it came to recording music, Sprey applied the same no-nonsense approach that he did to helping design airplanes. He turned off all the lights, refrigerators, furnaces, and electronic devices in his house and put rubber baffles on the walls and ceiling “to obtain as pure a sound as possible,” wrote the Post.

“The remarkablly lifelike sound quality of Mapleshade CDs is a direct result of Pierre’s unconventional approach to good sound — and his unwillingness to accept the dogmatic conventional wisdom of audio engineers,” Mapleshade writes on its website. “In his own words, ‘The wonderful thing about high end is the principle that only your ears count.’”

Many people’s ears were pleased to hear Mapleshade’s 1997 recording of the Addicts Rehabilitation Center (ARC) Choir. Each of the 32 singers in the Harlem-based choir was a former drug user who had been through or were still participating in the ARC program, The Boston Globe wrote at the time. Mapleshade recorded the choir singing in New York City, an effort for which the label received high praise.

“This is a recording that will set you on fire,” wrote one reviewer for the magazine Stereophile. “You’ll want to play the disc loud — imagine 32 people singing their hearts out in your living room.”

Kanye West seemed to get the message. The recording, made by the same guy who pursued purity in music and military aircraft, seemed to anchor Jesus Walks, an intricate song rich with overlapping sounds drawn from a wide range including a drill sergeant and West’s own voice.

“Kanye makes his spiritual toil sound like triumph thanks to marital drums and a little gospel choir fervor, sounding a clarion call of salvation to all would-be doubters and haters,” wrote Stylus Magazine in a review of West’s 2004 debut album The College Dropout, which features Jesus Walks.

Others also pointed out the song’s militaristic style, especially since it starts with West saying “We at war. We at war with terrorism, racism, but most of all we at war with ourselves.” That style no doubt helped set the tone of the Jarhead trailer.

Whatever secret ingredient was in Jesus Walks” it seemed to work. The song hit the 11th spot on the Billboard Hot 100, was awarded the Grammy Award for Best Rap Song and was nominated for Song of the Year. Sprey told the Post that the royalties from Jesus Walks‘ were enough “to support 30 of my money-losing jazz albums.”

You might never think that an A-10 Warthog and a 1997 recording of a gospel choir might have something in common, but for Sprey they did. They both seemed to follow the same guidance that Sprey once shared with the Post.

“The whole essence of this,” he said, “is to judge everything by outcomes.”

CORRECTION: 9/7/2022; An earlier version of this article inaccurately gave the impression that Pierre Sprey alone designed the A-10. That is incorrect. The A-10 was designed by a team of analysts and engineers, of which Sprey was a key member.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- The Navy’s ‘ghost fleet’ is growing

- Watch Iran try (and fail) to kidnap an American drone boat at sea

- Little Debbie snacks are being retired from service at military commissaries

- We salute the airmen who got 300 Chick-fil-A sandwiches flown in to feed their buddies

- Watch an Air Force pararescue vet fight off an alligator attack with his bare hands

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.