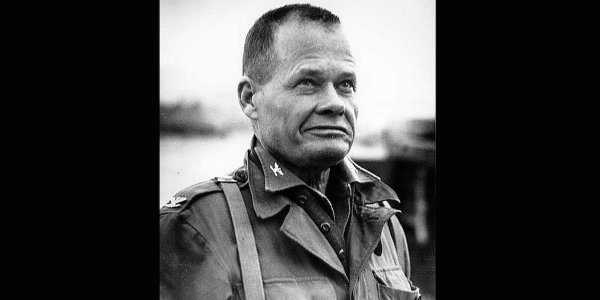

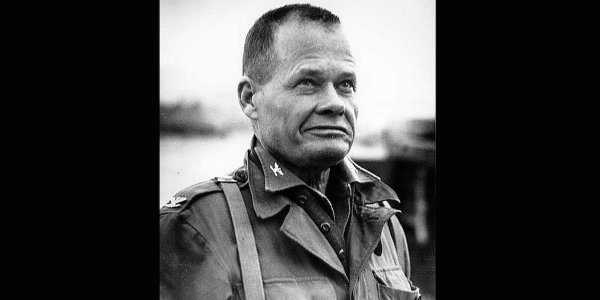

Lewis Burwell “Chesty” Puller, born in the 19th century, fought in the heaviest fighting of the 20th century, and is now a legend in this century. The most decorated Marine to ever wear the uniform, and also the most beloved, Puller left a mark on the Marine Corps that would define its culture for years to come.

Over his nearly four decades of service, Puller earned many commendations for what he did in combat, most notably the Silver Star, Distinguished Service Cross, and five Navy Crosses.

Here is how he earned those Navy Crosses.

Hunting guerrilla forces in Nicaragua.

Puller finished Officer Training Camp in 1919, just missing World War I, and then earned a commission again in Haiti fighting the Caco rebels. This combat experience taught him a lot about guerilla warfare, and he used that experience in Nicaragua.

Puller’s first received the Navy Cross during the Second Nicaraguan Campaign as a first lieutenant leading a small force of Nicaragua’s National Guard in 1930. Puller’s company, Company M, would earn itself infamy among the rebels due to the ferocity they would employ in flushing them out.

The purpose of the campaign was to protect U.S. civilians and economic interests in the country after fighting broke out between a U.S.-backed government and a guerrilla force under Augusto César Sandino. The Marine Corps was sent to train and lead the new National Guard forces against the insurgents.

Puller’s citation states that between Feb. 16 and Aug. 19, 1930, he systematically “led his forces into five successful engagements against superior numbers of armed bandit forces.” Hunting the insurgents through the jungles, Puller persecuted the enemy relentlessly.

His actions, which “dealt five successive and severe blows against organized banditry,” were exceptional and would begin his legacy as a five-time recipient of the second-highest commendation for valor in combat.

Puller’s tenacity would earn him the nickname, “El Tigre,” in Nicaragua.

Fending off ambush after ambush in the jungles of Nicaragua.

Two years later, again during the Second Nicaraguan Campaign, in September 1932, Puller and his company of 40 Nicaraguan soldiers were on patrol 100 miles north of the nearest base in Jinotega. After a six-day march, an insurgent force more than three times the size of the platoon ambushed them, according to Puller’s citation.

The gunfire killed the Nicaraguan soldier directly behind Puller, and seriously wounded his second in command. Responding immediately, Puller directed his men aggressively attacking the insurgents who were emplaced on the high ground to the right. Once overtaken, Puller used the high ground to overrun the insurgents on the left of his original position and scatter the remaining ambushers.

Only two of Puller’s 40 men were killed, six were wounded, while the opposing force of 150 was entirely decimated and scattered.

This was considered an important victory for the campaign, but would only be the first ambush on that patrol. While returning to Jinotega, Puller’s contingent was ambushed by forces twice more, and both times, Puller and his men repelled the attackers inflicting considerable losses.

He was subsequently awarded his second Navy Cross.

Holding a mile-long front against a larger enemy force on Guadalcanal.

It would be a decade before Puller would receive his third Navy Cross; this time during the battle for Guadalcanal on Oct. 24, 1942. Located in the Solomon Islands, Guadalcanal is renowned for the fierce and protracted close combat that was necessary during the Pacific campaign to push the Japanese back.

Puller, at this point a lieutenant colonel, commanded the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division, holding a line over a mile long, according to Puller’s citation. The rain and dense jungle made the task all the more difficult.

The Japanese force, far greater in number than Puller’s own forces, assaulted the line with a remarkable tenacity, but they held the line one man to every five yards, The New York Times recounted. By 3:30 a.m. the Japanese had launched six major assaults on Puller’s line. The final assault came around dawn.

Throughout the entire night, Puller retained calm and control and maintained the position of his battalion until reinforcements arrived after three hours of fighting, and even held command through noon the following day.

“By his tireless devotion to duty and cool judgement under fire, he prevented a hostile penetration of our lines and was largely responsible for the successful defense of the sector,” his citation states.

Turning the tide of a battle after taking emergency command of troops.

Puller earned his fourth Navy Cross while serving as executive officer of the 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division in December 1943, while fighting Japanese forces in Cape Gloucester, New Britain, Papua New Guinea.

“Chesty,” a 2002 biography by military historian and Marine Corps Reserve Col. Jon T. Hoffman, describes the events in which multiple company commanders were not aggressive enough to gain on the Japanese during a week-long attempt to take a strategically valuable ridge. Puller’s superiors sent him with orders to “continue the attack immediately,” and Puller, rather than just delivering the orders, also relieved the company’s commander.

Puller immediately moved the company forward, which had stalled at a creekbed, and established contact with the rest of the battalion in preparation for another assault. On orders, Puller stayed with the regimental commander and helped direct the movement of the troops, but before long, he was placed in charge of the regiment as well.

“Assigned temporary command of the third battalion,” his citation reads, “Puller quickly reorganized and advanced his unit,” seizing the objective almost immediately. Puller later moved from company to company on the front lines while braving rifle, machine-gun, and mortar fire from the Japanese to raise morale. He reorganized his troops and ensured the critical position they had was held, while also pushing them forward.

“His forceful leadership and gallant fighting spirit under the most hazardous conditions were contributing factors in the defeat of the enemy during this campaign,” according to his citation.

Defending division supply roots against an outnumbering force in sub-zero weather.

Puller received his fifth and final Navy Cross during the Korean War in December 1950. Puller, a colonel at the time, was cited for “extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy of the United Nations,” as commanding officer of the 1st Marines, 1st Marine Division.

According to The New York Times, Puller gave his men a short speech just a few months before, in the days preceding their landing on Korea: “We are the most fortunate of men. There was a time when a professional soldier had to wait twenty-five years or so before he ever got into a war. We only had to wait five years for this one. For all that time we have been sitting on our fat behinds drawing our pay. Now we are going to earn it.”

Puller made sure they earned it.

The battle took place in sub-zero temperatures against a North Korean force much larger than Puller’s own. He and his men fended off multiple enemy attacks on the “ defense sector and supply points,” says his citation. Moving along the front line, Puller was exposed to significant machine-gun fire, as well as artillery and mortar fire that was considerably threatening to the security of the line. Moving along his men “to ensure[sic] their correct tactical employment,” Puller successfully reinforced the front lines as demanded and kept the supply routes open for the entire division.

As the Marines and the Army moved from Koto-ri to Hungnam, Puller defended against two additional large enemy assaults and personally oversaw the treatment and evacuation of wounded men.

“By his unflagging determination, he served to inspire his men to heroic efforts in defense of their positions,” his citation concludes.

A fitting description of his entire career in the U.S. Marines.