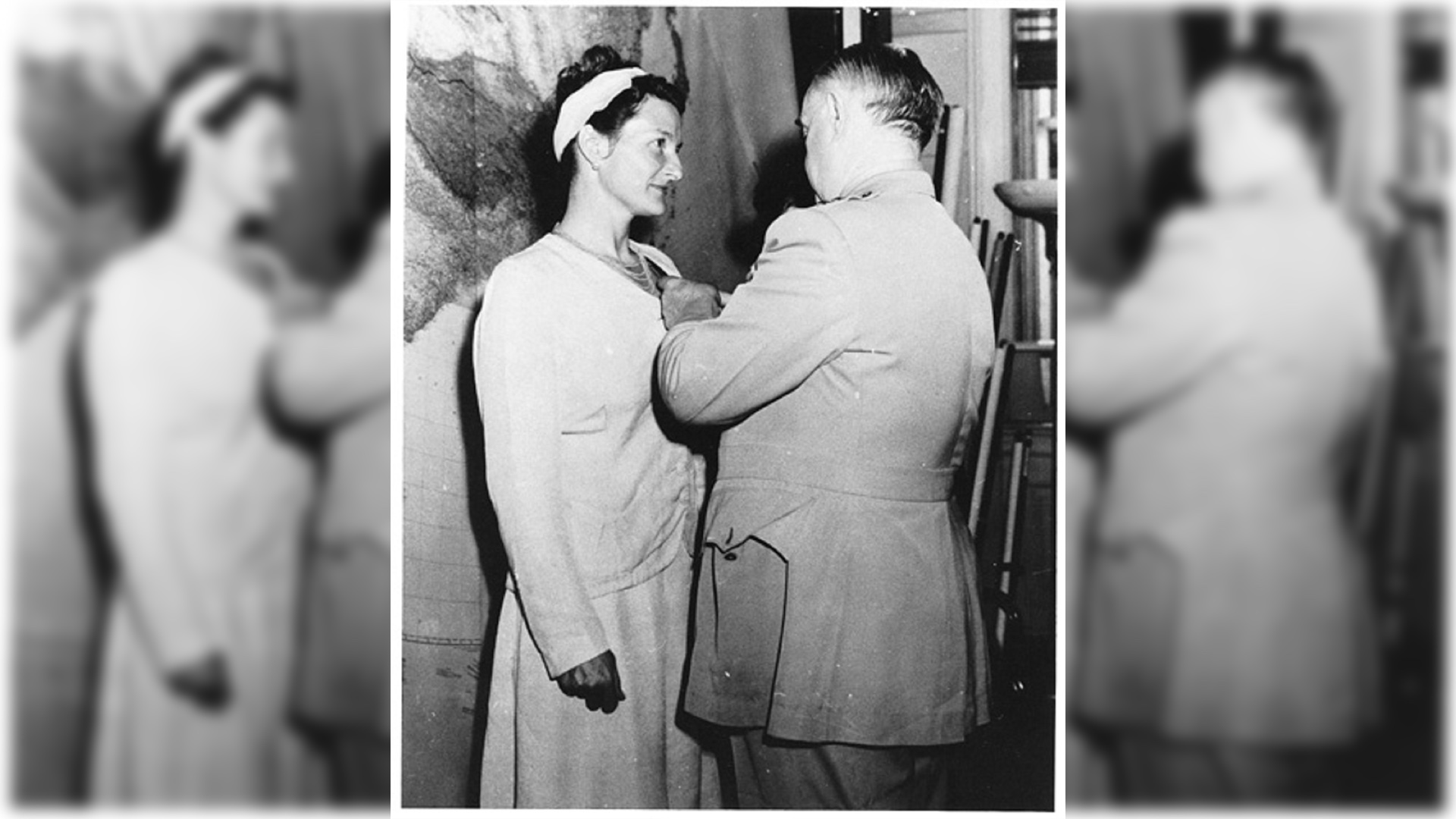

In September 1945, just as World War II ended, a small ceremony was held during which Virginia Hall was presented the Distinguished Service Cross by Maj. Gen. William Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Hall was the only civilian woman to receive the award, the Army’s second-highest decoration for valor, during the war. She had spent years undercover in occupied France, gathering intelligence, helping downed pilots evade capture, and eventually organized more than a thousand resistance fighters to conduct sabotage operations. Due to her efforts, she had been declared the Allies’ “most dangerous spy,” but the ceremony was kept private to protect her identity as she went on to serve in the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency for another two decades.

By the time Hall joined the OSS and eventually received her commendation, though, she was already an experienced intelligence agent.

Hall was born in 1906, to an affluent Baltimore, Maryland family. After studying briefly at Radcliffe and Barnard colleges, she moved to Paris, hoping to become a diplomat with the State Department. The prospects for such employment were slim to none for most women at the time, and Hall could only land a clerical job, first at the embassy in Poland and later at a consular office in Turkey.

After a hunting accident there, her left leg was amputated below the knee, necessitating the use of a wooden prosthetic for the rest of her life.

“She had been given a second chance at life and wasn’t going to waste it. And her injury, in fact, might have kind of bolstered her or reawakened her resilience so that she was in fact able to do great things,” Craig Gralley, a retired CIA officer who wrote a biography about Hall, told NPR in 2019.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest in military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

In 1939, with war breaking out across Europe, Hall volunteered to drive an ambulance in France. With France’s defeat, she was forced to move to London, where she caught the eye of Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE), which was tasked with conducting espionage and irregular warfare in occupied territory. As the citizen of a then-neutral country who could speak French and had traveled extensively in the region, Hall was sent back to France as the agency’s first female operative, posing as a reporter for the New York Post while she operated in the cities of Toulon and Lyon.

Initially sent only to collect intelligence on economic and political conditions in occupied France, Hall’s mission soon grew to encompass reporting on German troop movements, documenting the construction of submarine bases and recruiting a network of other spies to operate in the country.

Under the codename Heckler, the mission became the primary hub for British spy operations in France, supplying agents with money, documents and safehouses, covertly shuttling downed airmen around the country, and providing information on German military activity.

It was dangerous work, as around 25% of SOE agents were killed during their missions, and many others would face torture and deportation to concentration camps when captured. That includes 39 women agents sent to France by the Special Operations Executive — a third of whom never returned.

Adept at disguise, and with her seemingly unassuming demeanor, Hall evaded detection for a year.

“She could be four different women in the space of an afternoon, with four different code names,” said Sonia Purnell, author of the Hall biography “A Woman of No Importance,” in a 2019 interview with NPR.

During her time in Lyon, the Gestapo was never able to identify Hall, who operated under the codename “Germaine”, knowing only that they were pursuing a “limping lady.”

Among her pursuers was Klaus Barbie, known as the “Butcher of Lyon,” who circulated wanted posters of “Germaine” that declared her “The Enemy’s Most Dangerous Spy – We Must Destroy Her!”

Barbie would later escape to South America, before being arrested and returned to France in 1983.

With the Allied invasion of North Africa in late 1942 and the German occupation of Vichy France, Hall was forced to flee the country. In November of that year, Hall trekked 50 miles across a snowy, 7,500-foot pass through the Pyrenees Mountains to Spain. She was briefly arrested there, but eventually secured her release.

Once back in London, British intelligence considered Hall too compromised by the Gestapo to return to France, but it was now 1944 and the American-led OSS was expanding its own operations in France ahead of the planned invasion of Normandy.

In March 1944, under the codename “Diane,” Hall was back in France, once again relying on her guile and disguises to remain undetected.

“She got some makeup artist to teach her how to draw wrinkles on her face,” said Purnell. “She also got a fierce, a rather sort of scary London dentist to grind down her lovely, white American teeth so that she looked like a French milkmaid.”

However, Hall’s superiors at the time were wary of placing a woman in charge of such an operation, and so the OSS would only make her a deputy. Nonetheless, Hall made her way back to Paris, where she began organizing more than a thousand resistance fighters. They would go on to spend months blowing up bridges, cutting telephone lines, and conducting ambushes — with Hall reporting almost daily to London about their activities — ahead of the Allied landings in Normandy and the subsequent advance across Europe and into Germany.

By the end of 1944, France had largely been liberated, and while Hall was selected for another mission in Austria, the war in Europe ended before it was carried out.

Hall continued her intelligence work with the CIA until her retirement in 1966, but she was relegated to office duties. The nature of this activity also meant that her accomplishments remained fairly unknown for years. In addition to the Distinguished Service Cross, which then-President Harry Truman had offered to present publicly before Hall declined, she was also made a member of the Order of the British Empire. Once more Hall was recognized for her valor with little fanfare, so as to not compromise her identity.

Hall passed away in 1982, but in recent years her story, as well as those of other women who worked for the OSS and other intelligence organizations during World War II, have begun to be shared and given the public recognition they deserve. And while Hall rarely, if ever, talked about her accomplishments, the “limping lady” can be remembered as one of the most formidable spies of World War II.

What’s new on Task & Purpose

- A photo apparently showing Russian troops stranded in an elevator is going viral

- A Marine special ops commander explains why Russia’s stalled advance in Ukraine is no surprise

- How the US can beat Russia in Ukraine without firing a shot

- ‘My training took over’ — This Air Force cop went on a 100 mph car chase to arrest suspect

- In search of a just war: Why American veterans are answering a call to serve in Ukraine

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.