Sunday, Jan. 17, will mark the 55th anniversary of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s famous “military-industrial complex” speech. His key warning, “In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex” is what most people recall of this speech. It was taken to be a harbinger of the things that followed: the Vietnam War, massive defense spending, and increased American military involvement around the world.

But was that really the point that Eisenhower was trying to get across in his farewell address? In many ways, his address was a warning to the American people that is as timely now as it was then: The world is entering an era of persistent conflict and America must be prepared to accept that, as well as the costs of being a leader in the world community. It also must be ready and guarded to take on the dangers and pitfalls that are the flipside to having a large, modernized, and ever-developing military.

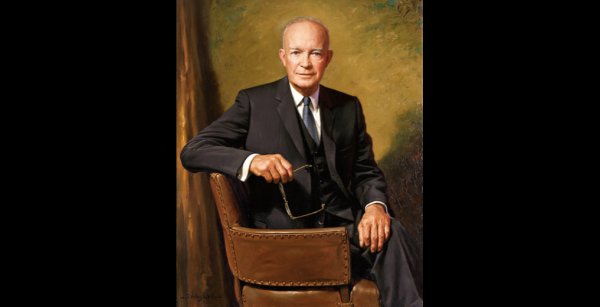

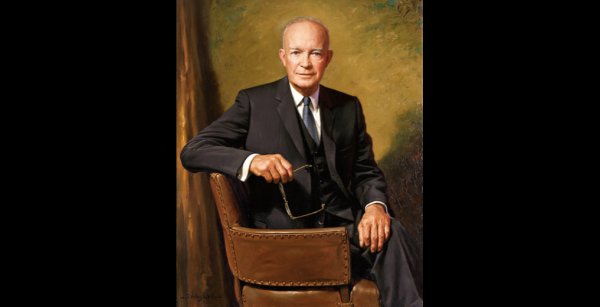

Eisenhower was at the end of his presidency. He could look back across a long career that encompassed military service in World War I (stateside), the post-war military cuts, service as Supreme Allied Commander in World War II, and as president from 1953–1961. The world had changed much in his time, but Eisenhower believed that America’s role in the world had not.

“Throughout America’s adventure in free government, our basic purposes have been to keep the peace; to foster progress in human achievement, and to enhance liberty, dignity and integrity among people and among nations,” Eisenhower said.

Little has changed since 1961 in that regard. Our main threat, or foe, if you will, has changed. Communism was the enemy of the day. “Progress toward these noble goals is persistently threatened by the conflict now engulfing the world,” warned Eisenhower of communism. Today we face the dangers of global jihadi extremists who demonstrated their reach and destructive capability in the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Since then, we have engaged in two protracted conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, which still continue to this day, echoing Eisenhower’s statement, “Unhappily the danger it poses promises to be of indefinite duration.” With hindsight being 20/20, we take it for granted that the Soviet Union would meet its end in the 1990s. That was not clear in 1961; indeed, the struggle against the ideology of communism lasted 30 years after Eisenhower left office.

Our current struggle against the so-called Islamic State continues, with many calling for a more aggressive strategy. Similarly, many in the United States demanded that the nation take a more belligerent stance against communism. To them, Eisenhower said,

… there is a recurring temptation to feel that some spectacular and costly action could become the miraculous solution to all current difficulties. … But each proposal must be weighed in the light of a broader consideration: the need to maintain balance in and among national programs — balance between the private and the public economy, balance between cost and hoped for advantage — balance between the clearly necessary and the comfortably desirable; balance between our essential requirements as a nation and the duties imposed by the nation upon the individual; balance between actions of the moment and the national welfare of the future. Good judgment seeks balance and progress; lack of it eventually finds imbalance and frustration.

This “spectacular and costly action” could be the Vietnam War, an advise-and-assist mission that slowly escalated over a decade to a full-blown war until popular support ebbed. It could be seen as the invasion of Iraq in 2003, or a ground conflict against the so-called Islamic State. This is a debate for historians and political scientists. Did the Vietnam War play a part in halting the spread of communism? Did the invasion of Iraq make the Arab Spring possible? These questions have been and will continue to be debated for the foreseeable future.

But was Eisenhower saying that we need to avoid military involvement all together? Hardly. Eisenhower was a man of military background. He, of all people, understood the dangers of cutting military force. In the period between the world wars, he watched as the U.S. military shrank in size and capability, and knew the consequences of such cuts. In his speech, he stated, “A vital element in keeping the peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction.” As if to acknowledge that he was breaking from the pre-World War II precedent, he stated, “Our military organization today bears little relation to that known by any of my predecessors in peacetime, or indeed by the fighting men of World War II or Korea.” In this, he was correct. The military stood at a height of readiness, both in manpower and technology, that was unheard of for a time of peace.

At the same time, Eisenhower saw that this militarization, while necessary for countering the threat of communism, was a double-edged sword:

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence — economic, political, even spiritual — is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

It is here that Eisenhower issues his warning, that “we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.” Eisenhower is not saying that we should return to a small military with a small budget, but that “an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.” This was Eisenhower’s warning: We are creating a tool to enhance liberty and freedom, but it has the capability to negate both, if left unfettered.

“It is the task of statesmanship,” said Eisenhower, “to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system — ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.”

As if to peer into the future, Eisenhower veered into the prophetic, stating,

… we — you and I, and our government — must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering, for our own ease and convenience, the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without risking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage. We want democracy to survive for all generations to come, not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow.

In this, he touches again on current issues of individual freedom, of balancing security with liberty, and warns against succumbing to the byproducts of the very ideology we oppose.

Indeed, in this year of presidential campaigns that seem to run on fear, Eisenhower’s words are eerily prescient: “Down the long lane of the history yet to be written America knows that this world of ours, ever growing smaller, must avoid becoming a community of dreadful fear and hate, and be instead, a proud confederation of mutual trust and respect.” It is this that Eisenhower wishes to convey, that even though we had built a massive military and created a military-industrial complex, we should not be looking for chances to use it: “Such a confederation must be one of equals. The weakest must come to the conference table with the same confidence as do we, protected as we are by our moral, economic, and military strength. That table, though scarred by many past frustrations, cannot be abandoned for the certain agony of the battlefield.”

Today, we see the fruits of the military-industrial complex: ever advancing technology, a massive defense budget, pet projects like the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter that seem to grow in cost day by day. We see a public and a government that has become used to using military force, whether drone strikes, special operations raids, air strikes, or even ground operations.

Eisenhower’s dual warning — against cutting our military force while also being wary of institutionalized militarization — holds as true today as it did in 1961.