From the outside looking in, the military lifestyle has a halcyon, Mayberry-type glow about it. Spouses, generally wives, stay home in their identical homes that military housing provides and keep house through deployment after temporary duty after deployment, watching the children who pause to render customs and courtesies during Retreat. Peter Van Buren even went so far as to claim that military communities, such as Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, recreate “the America of the glory days as accurately as a Hollywood movie.”

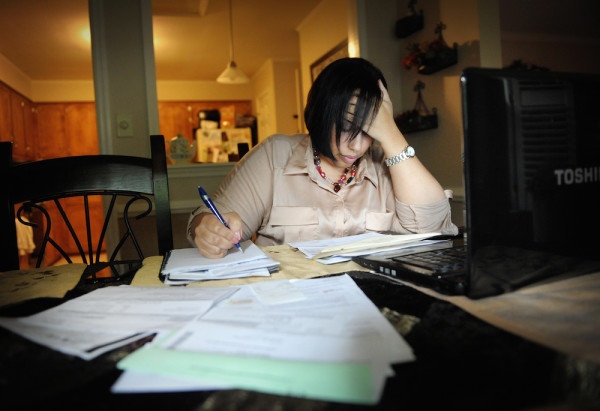

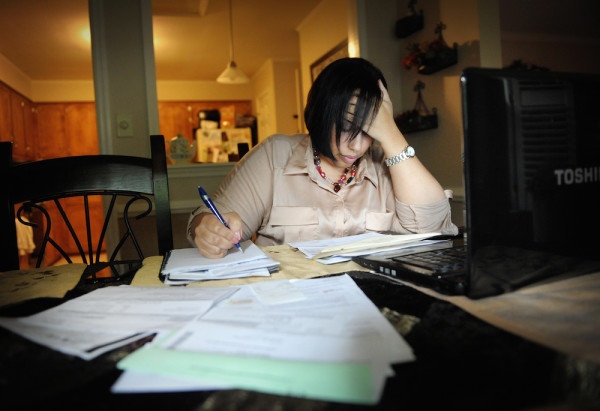

But if there’s one small flaw in this rendering it is this: Military spouses want to find employment, yet are struggling to work outside the home. As Congress increasingly eyes axing pay and benefits for military service members, this probably shouldn’t be all that surprising that more and more military spouses seek careers of their own to provide additional financial stability to their families (and maybe some personal career satisfaction). However, the Military Spouse Employment Report released by the Institute for Veterans and Military Families in February 2014 demonstrates that even though military spouses are generally better educated than civilian females in the workforce, they are more likely to be unemployed. For 18- to 24-year-old military spouses, the unemployment rate is as high as 30% — three times higher than their civilian equivalents — while 25- to 44-year-old spouses face an unemployment rate approaching 15%. For many, unemployment is not by choice. According to the report, “over 55% of respondents indicated they ‘need’ to work, while 90% indicated they ‘want’ to work.”

It would be easy to dismiss unemployment as a geographic anomaly, except that the report explicitly accounts for this, demonstrating the unemployment rate among military spouses can range from 29% in metropolitan areas all the way up to 40% in rural areas. Education, normally the pathway to employment in America, doesn’t even begin to bridge the divide between civilian and military spouses, with nearly 31% of unemployed military spouses holding a graduate degree. And should a military spouse be lucky enough to get a job, she or he is likely to face being underemployed according to education and skill level.

A noticeably large income gap between military spouses and civilian spouses continues to exist, with military spouses earning close to $15,000 less in 2012. Even something as innocuous as listing a residential address on a military installation can cost a female military spouse nearly $10,000 a year in gross income. Understandably, many spouses are reluctant to even admit that they are married to service members when searching for employment, with over 40% saying that they would not tell a prospective employer.

When I started my job search after finishing my military service and completing my master’s degree, I had no idea that six months after I started searching for a job, I would still be looking. While no prospective employer has explicitly stated that my husband’s military affiliation kept them from hiring me, one job application asked my marital status and where my spouse was employed, and in every interview I have gone to, they have all commented on the fact that my home address is on a military installation. Listing our home address made it easy for prospective employers to conclude that my husband is active-duty, but I assumed that employers would be eager to employ veterans and military spouses, or least weigh my experience over any other consideration. When I talked to other members of my community, I was horrified to hear that their experiences — and this report — largely echoed my own experience.

My friend, Megan, a prior Air Force officer married to her ROTC sweetheart, has yet to find a job after several months, even with veteran’s preference. Valerie left a management position to follow her husband across the country, only to remain unemployed for over six months without getting a callback on her applications (even with a college degree). When she asked the installation readiness center for assistance, they printed off a sheet of websites for her. Eventually, she took an entry-level position. Another friend, Nikki, has a college degree — and three little boys. While she would like to work outside the home, her husband’s schedule is too unstable for her to do so without also employing child care, which would then cost more than her potential salary.

It’s understandable, I suppose, that civilian employers would be hesitant to hire military spouses. Service members can deploy at a drop of a hat, leaving spouses home alone for months at a time, often with small children to care for. Or we could get orders to move with little-to-no notice across the country, and the employer could lose the time and money they spent training a military spouse.

And so if I could ask anything of an employer who looks at my resume and sees only an address on a military installation, or any other indicator that I am only a military spouse, it would be this: Please look beyond my husband’s uniform and see the military rank and the graduate degree that I earned. Do not assume that I am helpless, not when I have juggled a household as a single parent for months on end while I went through graduate school and he was halfway around the world. Please do not assume that I can’t arrange for back-up childcare or that I cannot be dependable because of his career. And do not assume that I cannot bring value to your organization simply because the man I fell in love with serves our country.

My fellow military spouses and I may not fit in Mayberry. But we may be a perfect fit for employers around the country — if we can just get the opportunity to prove it.