From cavalry to an M1 Abrams tank, mobility has always been key to military maneuvers. More than a hundred years ago, there was the bicycle. With the invention of the modern, chain-driven bicycle and pneumatic tires in the 1880s, the bicycle had emerged as a new form of rapid transportation. Several European armies had begun experimenting with utilizing bicycles for scouting and courier purposes.

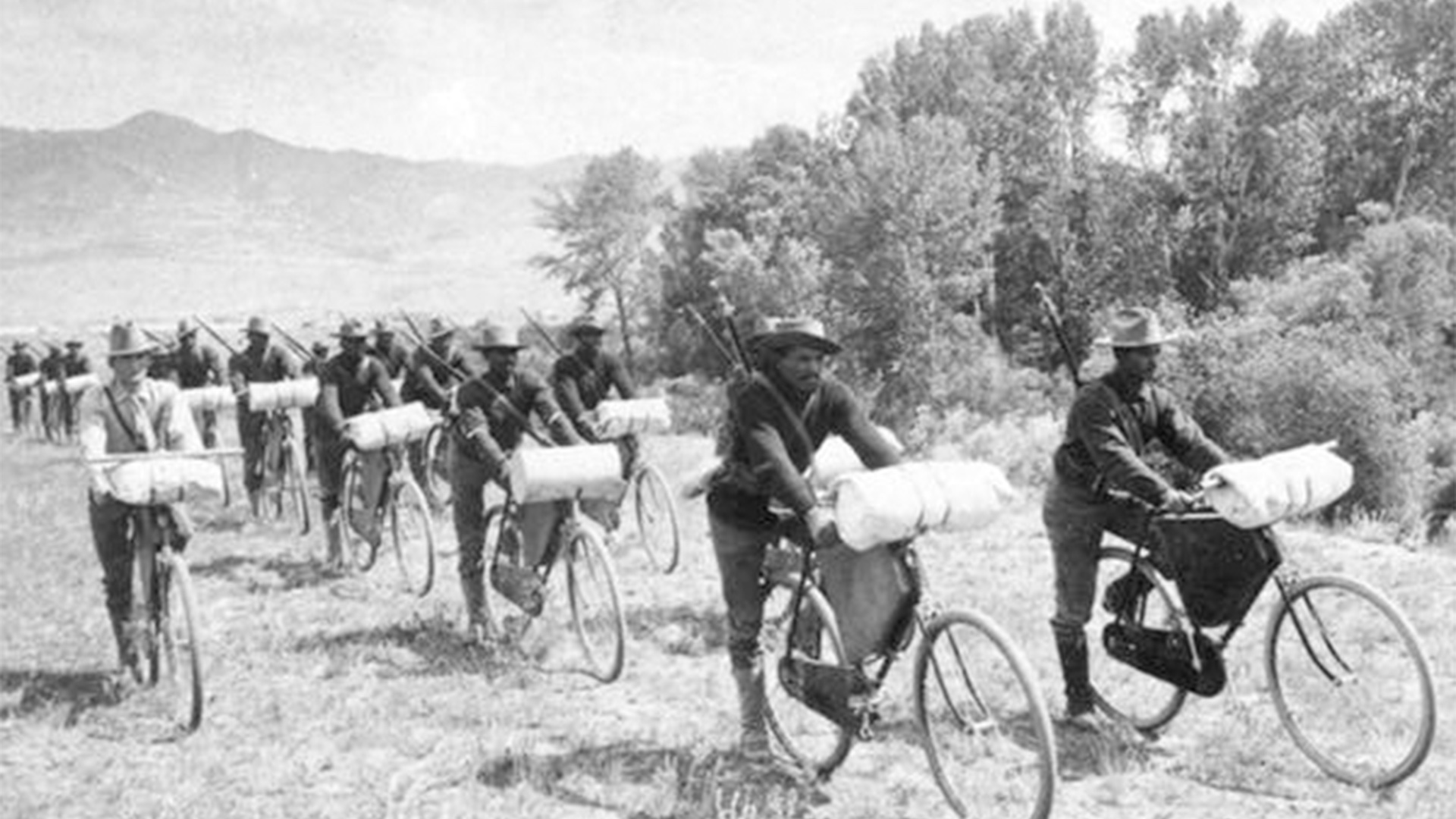

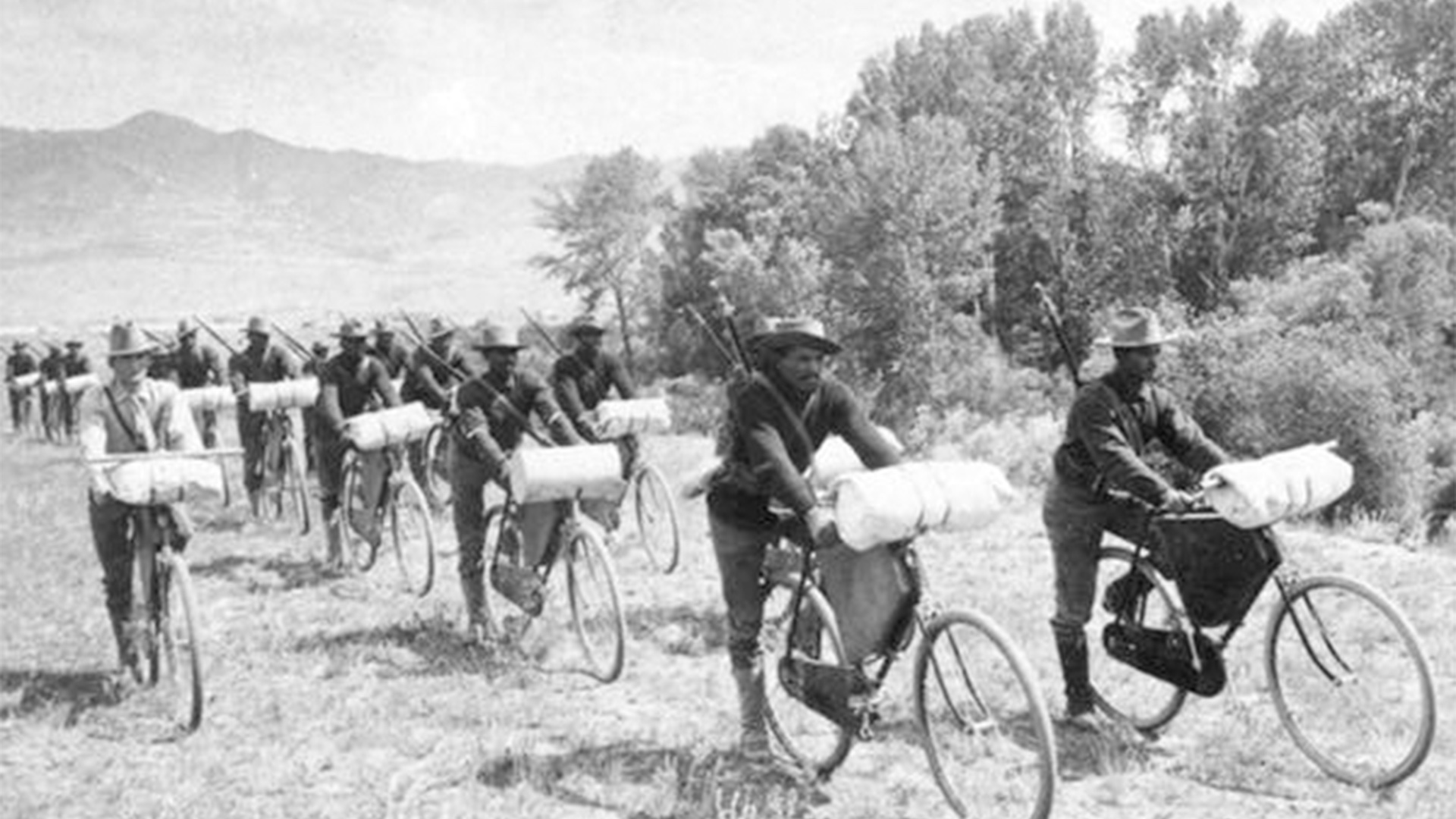

In the United States, that task fell to a small number of infantry troops assigned to the 25th Infantry Regiment at Fort Missoula, Montana, among the Army’s fabled “Buffalo Soldier” units comprised of Black soldiers.

For almost two months in the summer of 1897, a detachment from the 25th Infantry biked roughly 1,900 miles across the country, from Montana to St. Louis, Missouri, in an effort to prove the viability of the bicycle in military operations.

In 1896, the Army was a small, constabulary force, mostly spread out across remote outposts across the American West. Along with the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th Infantry, the 25th infantry had been established in 1866 as regiments of Black troops. Given the widespread prejudices of the era, the War Department kept these regiments stationed at some of the most distant forts of the frontier, fearing their presence would exacerbate racial tensions. From Texas to Oklahoma to the Dakotas, they had fought in numerous engagements during the American Indian Wars and had also been used to put down labor strikes and help build the infrastructure of the emerging frontier. The regiment had also seen two of its soldiers lynched.

“Black soldiers in the West were also engaged in nation-building of a different sort. By physically building the infrastructure that materially connected the West to the eastern states, such as roads and telegraph lines, and by forcefully putting down labor rebellions, African American soldiers shaped the former territories into states,” wrote historian Alexandra Koelle in the Western Historical Quarterly journal in 2010.

While an essential part of the Army’s presence in the West, service with the “Buffalo Soldiers” was sometimes considered an undesirable posting for white officers. Second Lt. James Moss, assigned to the 25th Infantry, had been the “Goat” of his class at West Point, graduating dead last.

He was also an avid cyclist and happened to have the ear of then-Maj. Gen. Nelson Miles, a strong proponent of modernizing the Army.

Two years earlier, in 1894, Miles had written that “There is no doubt in my mind that during the next great war the bicycle, with such modifications and adaptations as experience may suggest, will become a most important machine for military purposes.”

Not everyone was game. Moss’ own journal describes people referring to the bicycle as a “dandy horse.”

Still, the thinking went, a bicycle needed no food, no water, much less care, and didn’t have the temperament of a horse. The concept needed testing for a skeptical military, though, and who better to do so than Moss and soldiers of the 25th Infantry?

Supplied with specially modified bicycles from the Spalding Company (The same Spalding that makes volleyballs and basketballs these days), Moss and eight troopers of the 25th Infantry began their experimental cycling exercises in 1896.

The bikes, which weighed 59 pounds when fully equipped, were outfitted, “with a canvas tent, sleeping bag, and blanket that rolled up and attached to the handlebars, and a hard shell case that fit into the space in the middle of the frame, for further storage,” according to Atlas Obscura.

According to Moss’ journal, the packing list was comprised of “one shelter tent half and poles, one handkerchief, one knife, fork, spoon, cup and tin plate, toilet paper, tooth brush and powder. Every other man will take along one towel, one bicycle wiping cloth and one cake soap. Each chief of squad will carry one comb, one brush, and one box matches.”

All that along with rations and a 10-pound rifle on their backs with 50 rounds of ammunition.

Having completed a 125 round-trip journey the previous month, the bicycle corps set out in August 1896 for Yellowstone National Park. The roughly 800-mile round-trip journey took a little more than three weeks, including a five-day layover in the park.

Emboldened, the cyclist corps proposed an even longer expedition – an almost 2,000-mile ride from Fort Missoula to St. Louis, Missouri. As Moss’ journal described, the trip would cover all manner of conditions needed to prove the efficacy of the bicycle for use in war.

In 1897, 20 Black soldiers under acting 1st Sgt. Mingo Sanders were selected to accompany Moss, along with surgeon Dr. James Kennedy and Edward Boos, a newspaper reporter for the Daily Missoulian. Among them were five soldiers who had spent the previous summer cycling across the West.

The expedition set off on June 14, 1897, and as is typical of just about any military field exercise, was immediately confronted by rain.

Still, the soldiers pushed forward. This being 1897, roads were few and far between and often in poor condition, reduced to impassable mud tracks after heavy rain. Oftentimes, they were forced to ride along railway tracks as a means to cover ground. Moss’ journal recorded their crossing of the Continental Divide as taking place in freezing, blizzard conditions with visibility below 20 feet. Although the daily riding average was expected to be 50 miles, the terrain often left the group short of that goal, leaving them short on rations that had been left at pre-positioned points along the route.

Moss’ journal also details camping at the site of the Battle of the Little Big Horn and his soldiers’ trouble finding potable water and riding through the intense heat of a July summer on the great plains. There are also accounts of the spectacle of Black soldiers passing through towns where such a site was very uncommon.

After 40 days, the expedition arrived in St. Louis, utterly exhausted and escorted by a local club of bicycle enthusiasts. They had averaged between 52 and 60 miles per day.

The journey, however, would prove fruitless. Despite Moss requesting another expedition, it had failed to sway the Army in favor of a bicycle-mounted unit. Within a year the 25th Infantry Regiment would be recalled from the frontier and deployed to Cuba during the Spanish-American War. Later deploying to the Philippines, by the time the regiment returned stateside the automobile had overtaken the bicycle in the Army’s plans.

And while the bicycle didn’t take off in the US Army, it continued to see service in Europe. The first British soldier killed during the First World War, John Parr, was a scout sent forward to reconnoiter German positions on a bicycle.

The 25th Infantry Regiment was deactivated in 1957, after the integration of the military. And while the bicycle never entered the military arsenal, the two years spent crisscrossing the country on them in the most arduous of conditions is just one part of the “Buffalo Soldier” legacy of honorable service that will live on in the history books.

What’s hot on Task & Purpose

- The bitter debate over the Army’s fleece jacket is finally settled

- How ‘Starship Troopers’ inspired Jim Mattis to make infantry training more realistic

- ‘Cold, isolated, and stretched thin’ — Why so many airmen hate Minot Air Force Base

- Veterans donated to a woman who said she was a Marine combat vet dying of cancer. It was all a lie.

- An Air Force general openly shared his mental health appointment: ‘Warrior heart. No stigma’

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.