Explosive ordnance disposal units across the Army are struggling to train for combat operations amid both a personnel shortfall and a surge of domestic protection missions, a dangerous combination some EOD techs say has compromised their overall readiness and left their comrades burned out.

“We are burned out and it makes people not want to stay,” said an active-duty senior enlisted Army EOD tech who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “It makes us want to find other career options.”

When they’re home from a deployment, EOD personnel from each service branch frequently conduct Defense Support of Civilian Authorities (DSCA) missions, which include supporting local law enforcement and assisting in very important person (VIP) missions. But according to a

recent Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, the volume of missions has more than doubled over the past decade, from 248,000 man-hours in 2007 to 690,000 man-hours in 2017.

Making matters worse, military planners from each branch simply do not take those missions into account when they calculate how many EOD technicians they need for military operations in a given year, according to the GAO, resulting in personnel levels across the U.S. armed forces that don’t reflect the growing demand for non-combat EOD missions.

This increased strain is particularly acute for the Army, where the growing demand for EOD techs for VIP missions comes as the number of new EOD techs joining the ranks has plummeted.

According to data from U.S. Army Recruiting Command (USAREC), the service managed to persuade 1,283 fresh recruits to become EOD technicians in 2010. By 2019, the Army only recruited 250 people for the job, an alarming 80% decrease over a single decade.

“The workload has gone up exponentially while the people available to do that mission in the Army has gone down,” said one Army EOD officer, who also spoke to Task & Purpose on the condition of anonymity.

When reached for comment, Army spokesman Jason Waggoner told Task & Purpose that, contrary to the GAO report, the Army considers all missions, including DSCA missions, in determining resources for EOD force structure.

“The Army uses multiple homeland security scenarios in addition to war fighting scenarios to determine EOD requirements,” Waggoner said.

However, Army EOD techs themselves told Task & Purpose they feel understaffed and overworked, often without enough time to train for combat operations. Even worse, these conditions hurt morale and complicate efforts to attract new recruits and retain old hands, techs said.

“It’s a huge morale hit,” said the enlisted Army EOD tech.

Stretched thin

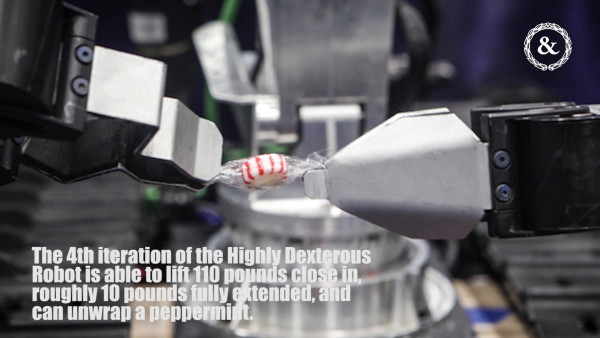

An Army EOD tech works to disarm a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) during training at the Henderson Fire Department in June 2019. (U.S. Army/ Staff Sgt. Ryan Getsie)

DSCA VIP missions, which often involve military canine teams searching for explosives or sweeping a motorcade route, are becoming a burden for EOD units. Traditionally, VIP missions requiring EOD techs have been reserved for current and former presidents, vice presidents, their family members and visiting foreign dignitaries.

However, EOD VIP missions have expanded in recent years. That’s in part because presidential candidates receive Secret Service details, which lack their own EOD teams, earlier in each election cycle, the Army EOD officer explained.

Certain VIP protection missions can be extremely manpower-intensive for EOD techs. In one instance detailed in the GAO report, a three-city, five-day visit by a foreign dignitary required

nearly 800 military EOD technicians. Though the report did not specify which dignitary, it may have been Pope Francis, since he visited Washington D.C., New York City and Philadelphia over the course of five days in 2015.

According to an enlisted EOD tech, VIP demand has also increased since Trump took office: Under the current administration, EOD units must also cover the Mar-a-Lago Club, the Trump Tower in New York City and the Trump National Golf Club in Bedminster, New Jersey.

Because VIP assignments are usually apportioned by location, units east of the Mississippi are tasked with conducting more Trump property missions, the enlisted tech explained. In fiscal year 2014, the enlisted tech’s battalion conducted 25 VIP missions, the tech said; by fiscal 2019, that number jumped to over 130 VIP missions, 11 of which were for Trump properties, with teams from the tech’s battalion conducting six rotations at Trump Tower in New York City.

The rising workload comes on top of existing assignments, such as protecting former presidents. While the soldiers in the enlisted tech’s unit still enjoy those VIP missions, the tech said “we just need a break.”

Soldiers in other units are completely sick of VIP missions.

“When I first came in, guys fought for [VIP missions],” said the EOD officer. “Even taking Jimmy Carter to church was a fun thing to do. You get to hobnob with the bigwigs and come back with cool stories. But now everybody hates them. There’s just so many.”

The core of the problem is simple. According to the GAO report, Pentagon planners simply aren’t using all the information at their disposal when evaluating their manpower needs. To fix this problem, the GAO recommends that the Defense Department update its guidelines to ensure that all EOD missions, including DSCA missions, are considered when calculating manpower requirements.

“While it is understandable that the services prioritize combat missions when determining EOD requirements, they are not considering all available information in their decision-making process,” the report wrote. “This lack of consideration limits their ability to efficiently and effectively achieve their objectives and manage risks.”

The enlisted tech said the Pentagon’s decision not to include domestic VIP missions in manpower calculations is particularly bothersome in part because EOD units have to keep meticulous records of every mission they conduct, combat or otherwise.

“I was surprised to see not take into account our stateside missions, because we have an incident database where we do a report on everything we do,” including VIP missions and the man-hours needed to accomplish them, the tech said.

Understaffed

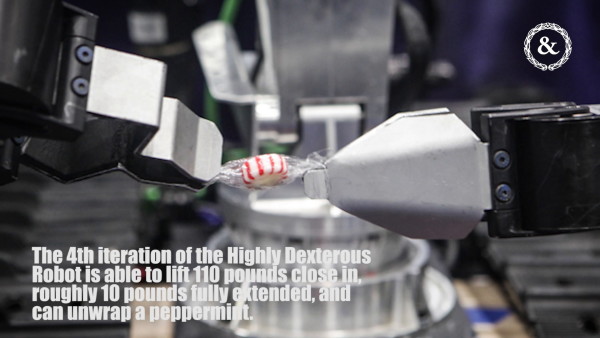

An Army EOD tech searches a tunnel for booby traps at Fort Carson, Colorado, June 14, 2017.

(U.S. Army photo)

While the DSCA issues cited in the GAO report are a problem across the armed forces, the Army is particularly hard hit. The uptick in VIP missions comes as the Army has actively reduced its EOD forces over the last five years. According to the GAO report, the Army shed 800 EOD positions — the equivalent of two EOD battalions and 13 EOD companies — since 2014 as part of a larger personnel cut driven by “force structure adjustments and the drawdown of EOD forces,” the report said. According to the EOD officer, that cut represented somewhere between 20% and 33% of the Army’s total EOD force.

“[VIP missions] wouldn’t be such a problem, at least in my service, if we hadn’t kicked a bunch of guys out in the past few years,” the officer said.

The officer said recruiting in general for Army EOD has never been a challenge, but recruiting people who will make it through the demanding EOD school is. When the officer was in EOD school, there was a 40% academic fail rate, the officer said, but that didn’t include students who were dropped for conduct or clearance reasons, such as getting arrested for driving under the influence.

At the time of publication, the Army was unable to provide attrition rates for Army EOD school to Task & Purpose.

EOD units were not always understaffed. From 2002 to 2012, the Department of Defense increased its EOD forces by more than 70 percent due to increased demand, according to the GAO report.

But after fiscal year 2013, there was a steep drop in the number of recruits joining the Army to become EOD technicians. Between fiscal years 2009 and 2013, the Army averaged 1,125 recruits pursuing EOD annually, according to the USAREC data. Over the next five fiscal years, from 2014 to 2018, that average fell to 334 EOD recruits a year. In fiscal year 2019, only 250 recruits joined the Army to become EOD techs.

The lower enlisted ranks were hit particularly hard by this decline, said the senior enlisted tech who spoke with Task & Purpose. Army EOD units are running at 40 to 50 percent capacity at the team level, the tech said.

The tech added that the manpower shortage has forced Army EOD teams to operate in pairs rather than in usual three-man teams. It’s become so bad, the tech added, that at one point Army EOD units in the U.S. pulled senior enlisted soldiers from the battalion, group and operations level and threw them in the field to carry out DCSA missions.

A blow to readiness

The cumulative effect of these challenges means EOD soldiers are missing out on critical training time, the techs said, resulting in serious readiness shortfalls. Indeed, the GAO report noted that the rising workload and falling manpower numbers mean EOD units are often so busy performing DSCA missions that they miss the critical training they need to prepare for combat.

“Fulfilling VIP support missions can be particularly difficult because short-notice demand for EOD teams often exceeds the planned VIP support demand,” the report states. “As a result, Army EOD teams are sometimes dispatched at the expense of military preparedness for combat-related missions.”

The Army isn’t the only one feeling the pinch: the GAO report said the Navy sometimes refuses requests to protect foreign dignitaries so that its techs can meet its training and readiness requirements. But that leaves other, already-strained services to pick up the slack, GAO writes. The report points out that, under Department of Defense guidance, the service branches aren’t required to report when VIP missions are hurting readiness.

That means there’s no requirement for services to tell the Joint Staff and combatant commands when EOD forces are stretched so thin doing VIP missions they don’t have time to train for combat. One of GAO’s recommendations is for DoD to change that guidance.

Besides missed training time, Army EOD techs are also running short on important down-time with family, not to mention personal pursuits like

interpretive dance. The EOD officer said there used to be enough technicians and few enough domestic civil authority missions to stay balanced.

“Before the rapid expansion of VIP mission workload and before we dropped those units, I felt like we had a pretty good grip on it,” the officer said. “It was a fun time to be in. You could deploy and when you got home you had time to do training and schools and do law enforcement missions and VIPs and see your family.”

But that’s no longer the case. “Something needs to change,” the officer said,” because I don’t think we have enough manpower for the workload.”

“People like to feel valued, and when they take that away people get frustrated and leave,” the enlisted tech added. “And it’s disappointing because we don’t fail. We never fail. We always accomplish our mission.”

The Army spokesman, Jason Waggoner, told Task & Purpose that Army leadership has made EOD growth a top priority. Beginning in fiscal year 2022, he said, EOD teams will grow from two-soldier teams to three-soldier teams in order to provide promotion potential for mid-level NCOs.

The Army has also increased enlistment and retention bonuses for EOD troops, Waggoner said.

“The Army will continue to monitor and take action to ensure its EOD forces are prepared to meet all current and future threats,” Waggoner added.

The Army also recently changed its uniform regulations so that EOD soldiers can

wear their brassards full-time. Before then, EOD soldiers could wear their brassards only while actively conducting disposal operations around non-EOD personnel in a combat zone.

The rule change is a nice perk, the enlisted tech said, and since then the tech has seen a few more people ask about the job. But they rarely sign up to give it a shot, the tech said.

Uncertainty ahead

While the GAO report drew

plenty of presscoverage, both Army EOD techs who spoke to Task & Purpose said they were unsure the report would prompt any change in how the services calculate EOD manpower requirements.

“We’re very jaded,” the enlisted tech said. “We see things like this all the time, reports that come out that confirm our suspicions that they’re not listening to us.”

The tech recalled the Army’s response to

news coverage last year of the death of Spc. James A. Slape (who was posthumously promoted to sergeant), a 23-year-old EOD tech attached to a National Guard unit deployed to Afghanistan. It was widely reported that the unit had repeatedly asked for certain training courses and equipment before its deployment which are considered standard for active-duty EOD teams.

The requests were denied due to lack of funding, reports said.

The incident led the Army to make some changes, said the enlisted tech who spoke with Task & Purpose.

However, the tech was skeptical the GAO report would prompt a similar response, since no EODs have died from being overworked. Even if the report does lead to the services changing their manpower calculations, it will take time, potentially years, before new techs arrive to help lighten the load. With a three-year runway to produce qualified, experienced EOD specialists, according to the GAO report, Army EOD units are constantly playing catch-up.

“Manning is not an easy fix,” the tech said. “You can’t just snap your fingers and say ‘here’s 100 more EOD techs.’ Our schooling is a year long and you have to find the right people for it.”

The enlisted tech would like to see other services pick up more VIP missions so that Army EOD units have more time for training. However, there are also second and third order effects looming on the horizon. The EOD officer noted that the strain comes at a difficult time strategically, as the military prepares for possible conflicts with near-peer adversaries such as Russia and China.

“I don’t think the era of great power conflict is over. And when that does happen, you can grow a new infantryman in nine weeks,” the officer said. “I can’t grow a new bomb technician in less than a year, so not having enough people seems short-sighted.”