Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in October 2019

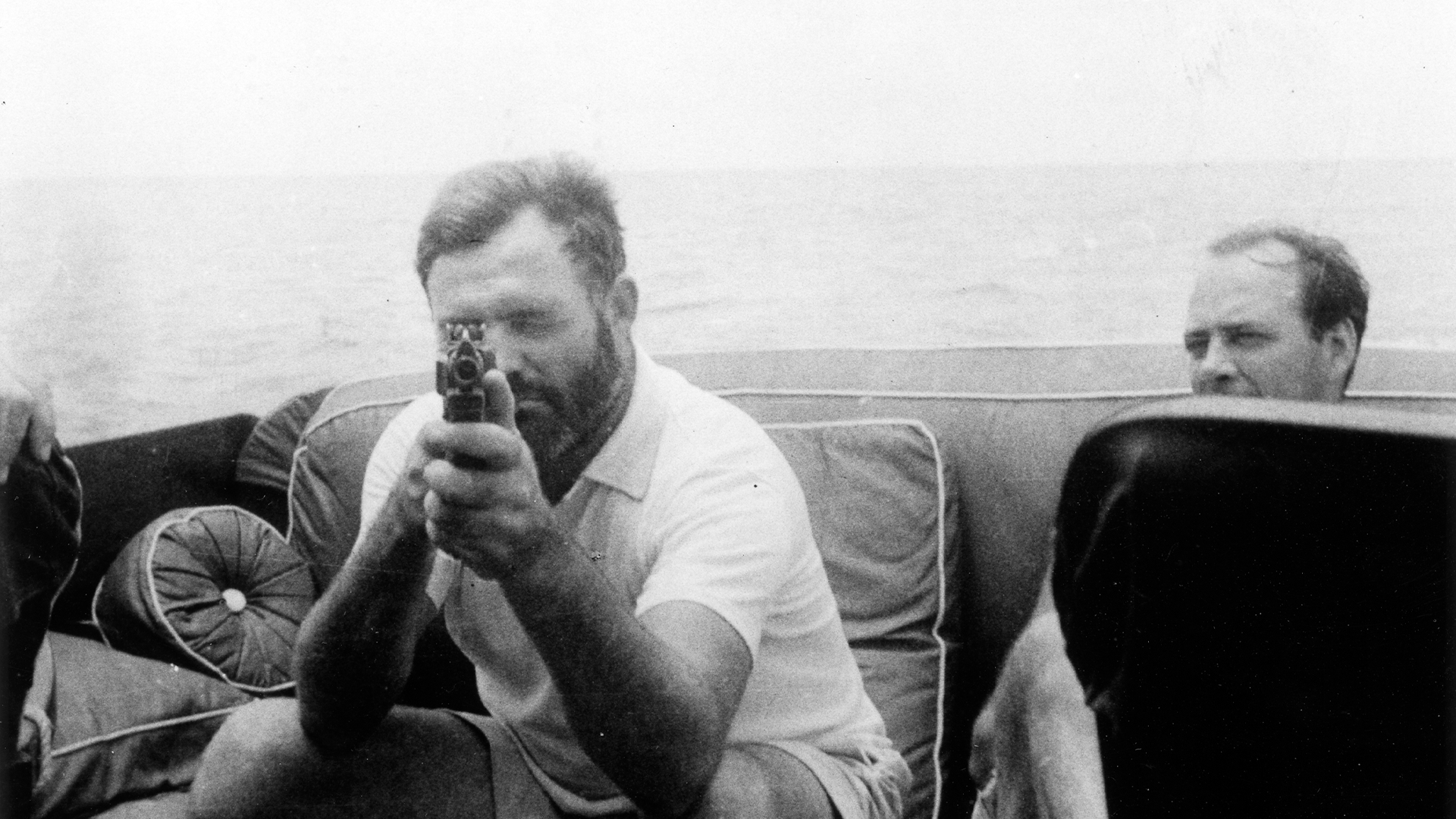

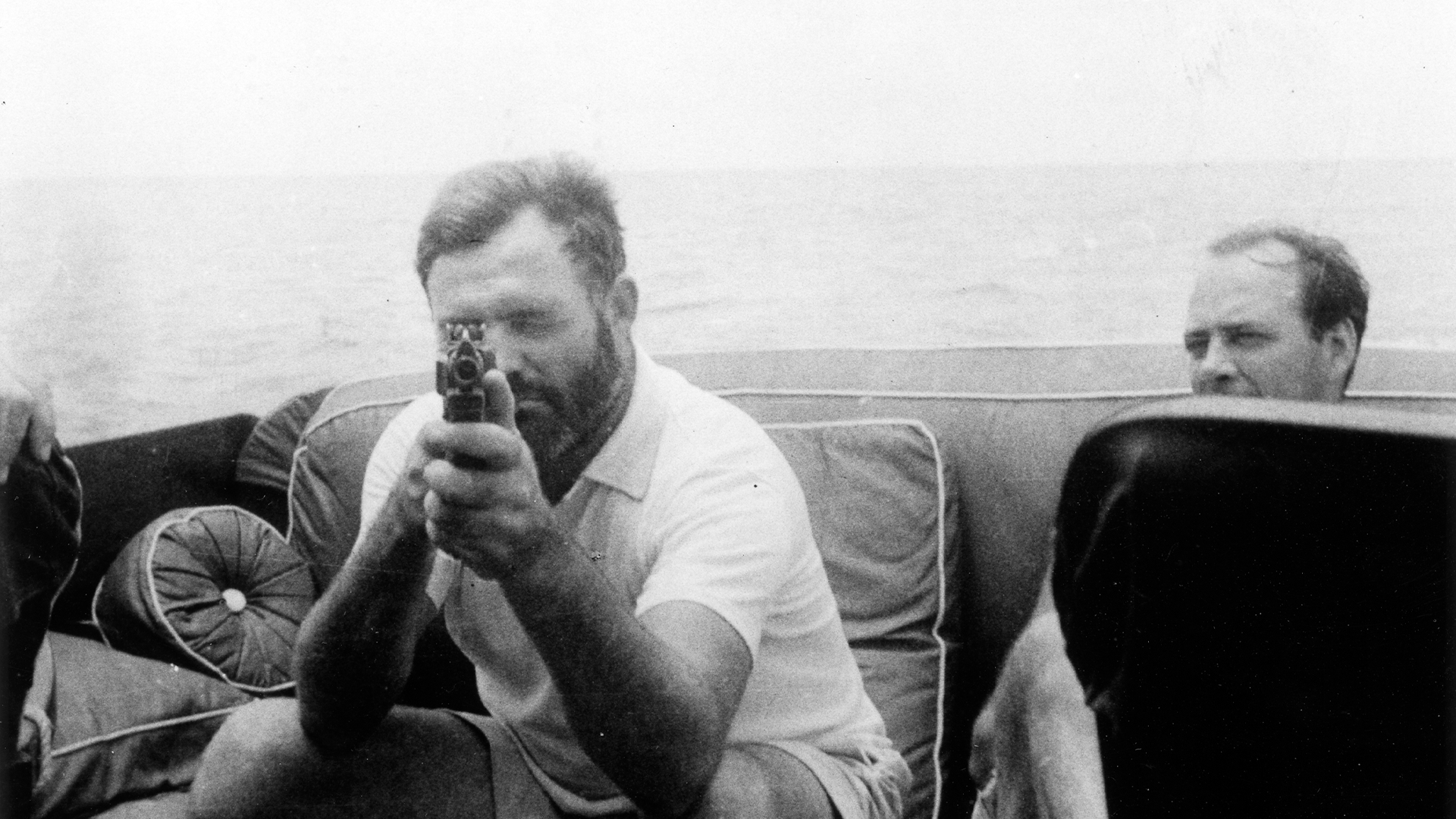

Long before Ernest Hemingway wrote, drank, and fought his way into the ranks of America’s legendary wordsmiths, the beloved author cut his literary teeth on the beat of a Canadian newspaper.

Fresh off a stint driving an ambulance for the Red Cross on the Italian front during World War I, the young Hemingway

landed at The Toronto Star Weekly in early 1920, where he covered everything from mobsters to the complete uselessness of wedding gifts — including the rise of stolen valor and the lousy market for war medals that accompanied the end of the Great War.

One of Hemingway’s funniest pieces was “Popular in Peace, Slacker in War,” a sarcastic, mocking lecture for the Canadian citizens who deployed not to the bloody trenches of war-torn Europe with the Canadian armed forces, but to relatively safe jobs in American munitions factories. Sensing these “morally courageous souls” might be a bit ashamed that they were not among their nearly 425,000 fellow countrymen who faced death overseas, the young Hemingway dispensed some sage words to help them pass themselves off as battle-hardened patriots.

Even in the 1920s, donning the proper attire was a crucial part of impersonating a real military man. For this, Hemingway suggests hitting the thrift store for a trench coat and maybe a pair of army boots, which will “convince everyone you meet on the streetcar that you have seen service,” allowing you to “have all the benefits of going to war and none of its drawbacks.”

The phony vet may also face inquiries about why he doesn’t sport the overseas badge of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, to which he should shoot back “I do not care to advertise my military service!” This retort, Hemingway says, will cause the real combat vet “brazenly wearing his button” to feel like a total blowhard.

Papa’s words of wisdom extend into the realm of seduction, too, one of the chief goals of any dirtbag who unjustly dons military dress. If a “sweet young thing at a dance” asks you if you ever met this or that major, he writes, “merely say ‘No,’ in a distant tone. That will put her in her place…” Looking wistfully into a glass of booze works well, too: As Hemingway himself knew, ladies love the strong, silent type.

The key to maintaining the ruse, of course, is research. Hemingway advises the pretend soldier to learn some classic French songs and to get his hands on a solid literary war history, which will empower him to “prove the average returned veteran a pinnacle of inaccuracy,” since “the average soldier has a very abominable memory for names and dates.” “With a little conscientious study,” he writes, “you should be able to prove to the man who was at first and second Ypres that he was not there at all.”

Acting the part is important, too. “Be modest and unassuming,” Hemingway goes on, “and you will have no trouble. If anyone at the office addresses you as ‘major,’ wave your hand, smile deprecatingly and say, ‘No; not quite major.’ After that,” he writes, “you will be known to the office as captain.”

Those unfamiliar with Hemingway’s sardonic, tongue-in-cheek style may take his guide literally, an actual roadmap to usurping the honor that comes with military service. But Papa makes his feelings about stolen valor very clear in the closing section of his piece.

“Now you have service at the front, proven patriotism and a commission firmly established, there is only one thing left to do,” writes Hemingway. “Go to your room alone some night. Take your bankbook out of your desk and read it through. Put it back in your desk. Stand in front of your mirror and look yourself in the eye and remember that there are fifty-six thousand Canadians dead in France and Flanders. Then turn out the light and go to bed.”

More great stories on Task & Purpose

- A Marine actually got a tattoo based on that cringe viral ‘He’s a Marine’ TikTok video

- Meet the Army sergeant who ran a makeshift orphanage in Kabul to care for children during the evacuation

- Hollywood is already making a movie about the Afghanistan withdrawal

- No ‘surrender’ — What really happened between US and British Marines at a training exercise

- Marine Corps throws cold water on fighter jet rides for reenlistment

- A woman just graduated the US Army’s sniper school for the first time ever

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Learn more here and be sure to check out more great stories on our homepage.