It’s been 10 years since I was a young private undergoing advanced individual training, or AIT, to become a combat medic at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. But I feel pretty confident in saying that the Army’s plan to install drill sergeants at AIT is bad, and that the idea it’s premised on is even worse: the fashionable notion that lazy, entitled millennials need an extra butt-whipping to be good soldiers.

During a virtual town hall meeting with soldiers last week, Command Sgt. Maj. Michael Gragg, the senior enlisted soldier at the Center for Initial Military Training, announced that the Army plans to replace the platoon sergeants currently assigned to AIT with drill sergeants by 2019. Drill sergeants were phased out of AIT nearly a decade ago, and Gragg has been spearheading the effort to bring them back. That effort has stalled because of budget issues, Army Times reports.

“Let me tell you how it was back in my day, when AIT drill sergeants roamed the Earth”

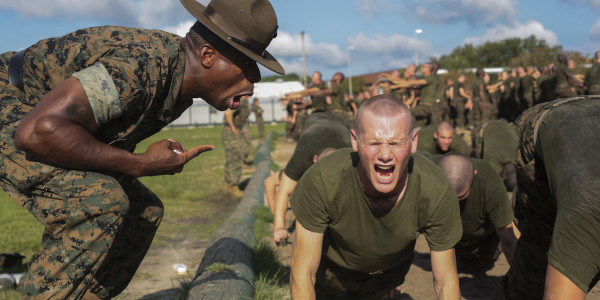

Drill sergeants are responsible for the initial shock-and-awe phase of the civilian-to-soldier transformation process, and they ran the show during my time at Fort Sam. The AIT I experienced was not the spit-shined utopia Gragg and other Army officials make it out to be now. And it was certainly not anything the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command should spend money trying to bring back.

Of course, Gragg, who enlisted in 1989, sees things differently. “Our AIT platoon sergeants are doing an outstanding job with the tools and skills that they have,” Gragg said in April 2016. “The problem that we do have is that right now the generation we have coming in is not as disciplined as we would like them to be, so we have to provide them with discipline over a longer period of time.”

Wait… what? When the Army decided to replace AIT drill sergeants with platoon sergeants in 2007, the rationale was this: Drill sergeants only exist within the confines of the training environment, and replacing them with platoon sergeants would better prepare soldiers for post-training life in the regular Army.

The logic made sense then, and it still makes sense today. The relationship between a soldier and his drill sergeant bears little resemblance to the relationship that soldier will have with the vast majority of senior-ranking NCOs he’ll encounter over the course of his career.

However, the AIT training environment has devolved into bedlam, according to Gragg — not because the platoon sergeants aren’t the epitome of professionalism, but because the trainees passing through their ranks embody all that is wrong with the young people our society is producing today.

It’s the same “back in my day” argument people have used for decades to advocate bringing paddling back to the classroom. Kids these days are soft as marshmallows! They need to be toughened up!

Well, let me tell you how it was back in my day, when AIT drill sergeants roamed the Earth.

The moment I arrived at Ft. Sam from basic training at Ft. Benning, I wasn’t the only private shocked to see a pack of drill sergeants waiting for us when we got off the bus. We were under the impression that the getting-the-shit-smoked-out-of-you-three-times-a-day period of training had ended, and now the focus would shift to learning to save lives on the battlefield. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were raging, and skilled medics were in high demand.

Don’t get me wrong: I learned a lot in AIT, and many of the drill sergeants inspired me to push myself to become the best “soldier medic” I could be. However, I certainly could’ve learned more. Doing 200 pushups because someone smuggled a bottle of vodka into the barracks and drank himself into a coma is great for building physical strength and endurance, but the resulting fatigue is hardly conducive to learning how to properly identify and treat a tension pneumothorax. And neither is staying up all night because the guys in Alpha bay decided to stage a “Gangs Of New York”-style brawl with the guys in Bravo.

But that was life at Fort Sam — a never-ending cycle of pushups and drama. It seemed like every other week another trainee went AWOL.

Now, I realize the scope of my experience is very limited, and there are plenty of people who went through AIT then who recall it with the fondness of a grizzly old man reminiscing about how much fun he had pulling 14-hour shifts in the coal mines. But my point is this: Drill sergeants in AIT won’t fix the problem of new recruits behaving badly, because drill sergeants didn’t fix it the first time they were there.

“It was a matter of trying to get them to associate authority with a figure other than the hat,” Gragg said of the Army’s decision to phase out AIT drill sergeants. “But what we didn’t realize and didn’t take into account is the drill sergeant in the AIT environment is still working on that soldier.”

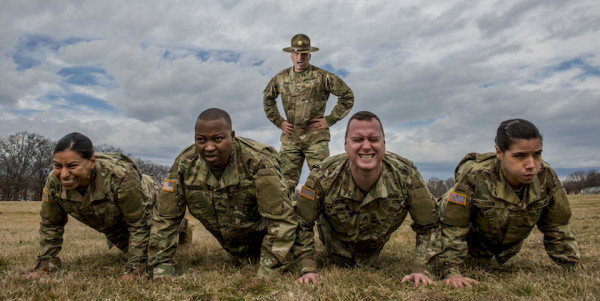

A U.S. Army drill sergeant corrects a recruit during her first day of training at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., Jan. 31, 2017.Army photo by Stephen Standifird

I served with medics from both eras that Gragg refers to, and when the ones who went through AIT sans drill sergeants told me about the Friday night orgies they had in the Motel 6 off I-35 in San Antonio, I wasn’t the least bit surprised. That was a thing back in ’06, too.

Old guys look down on new guys; that’s just how the world works. However, as far as I could tell, the only major difference between the old-timers’ AIT experience and mine was that I studied a lot less, and I got punished a lot more for shit I didn’t do. The units I served in downrange had good medics and bad medics, but it was impossible to trace those distinctions back to whether or not they had drill sergeants in AIT. Guys from both camps came back from overseas with medals on their chests.

Not all soldiers emerge from basic training more squared-away than they were on Day One, but the problem isn’t generational, nor is it due to a lack of knife hands to the face. Drill sergeants serve a vital function, but their ability to instill discipline has its limits. When the initial shock of being in the Army wears off, old habits resurface and soldiers start to bend the rules. A few choose not to play by them at all. That’s what Article 15s are for.

This is not a new phenomenon. During the Civil War, more than 300,000 Union and Confederate troops went AWOL. 50,000 Americans deserted during World War II, and 420,000 men were classified as deserters during Vietnam. The military can be a tough life, and AIT is a good place to determine who it is and isn’t for.

In 2006, the Army was pushing a lot of new soldiers through the training pipeline who never should’ve been recruited in the first place. The Pentagon needed bodies, and, as a result, those of us who were serious about the Army got stuck serving alongside many soldiers who weren’t. Today, the recruitment standards are higher, which is a step in the right direction, but bad apples are still slipping through the cracks.

They always will. More drill sergeants aren’t the solution. We know because we’ve tried this before. Perhaps now is the time to start developing a plan that stands a chance.