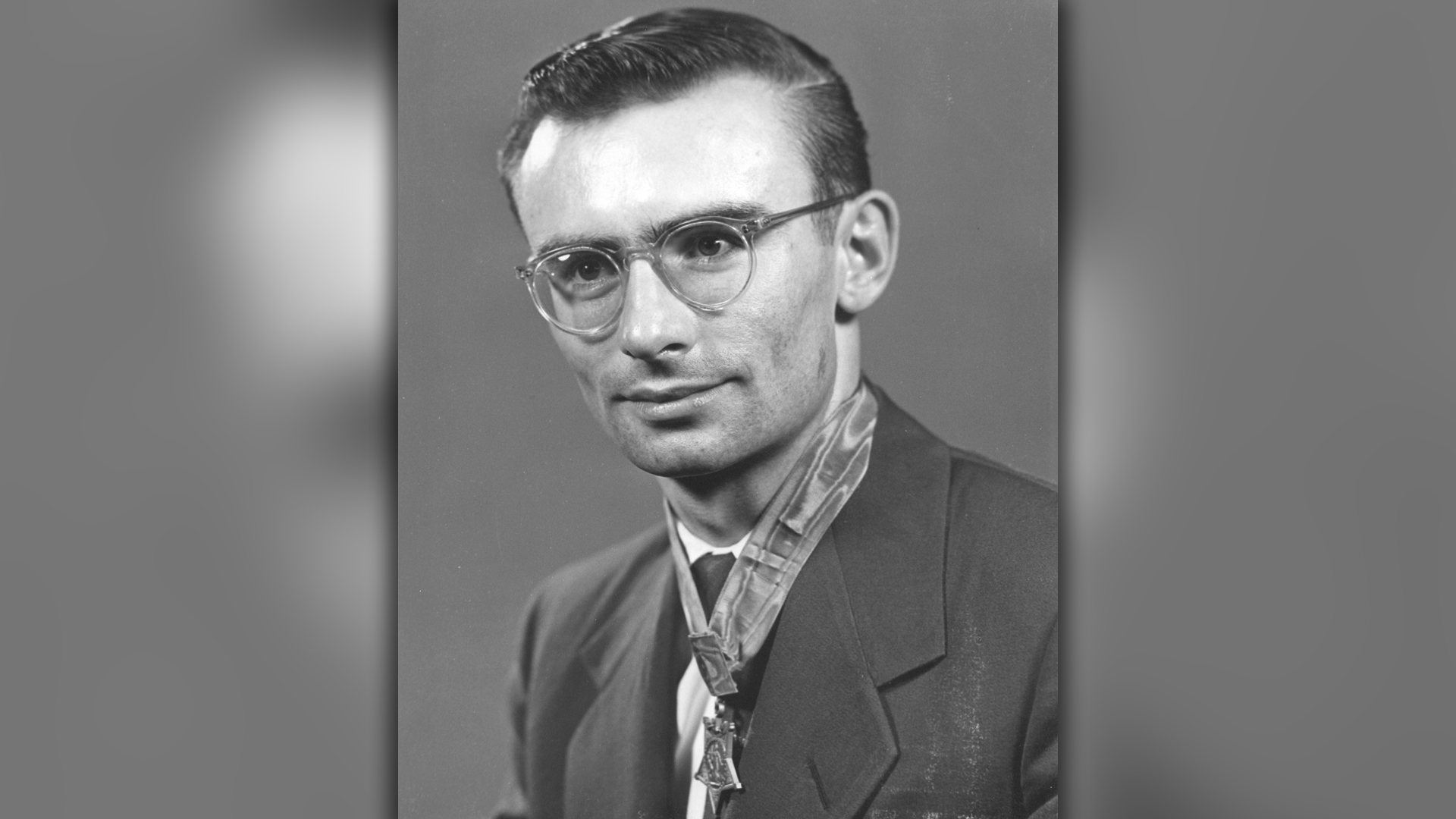

The Navy announced on Friday that it would name an upcoming support ship after Private 1st Class Robert E. Simanek, a Marine who was awarded the Medal of Honor after jumping on a grenade to save his fellow Marines in Korea 69 years ago — and survived to tell the tale.

The ship, a massive Lewis B. Puller-class expeditionary mobile base that weighs 100,000 tons when fully loaded, is the first to be named after Simanek, who was just another 22-year-old infantry grunt when he woke up on the morning of August 17, 1952.

“I’d been out all night and they had to use me again without any sleep,” the former rifleman and radioman recalled about that morning for an interview with the Veterans History Project. Simanek was assigned to Company F, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division when he was selected to go on a morning patrol to an area called Outpost Irene, just north of Seoul, according to a 2020 DoD article written about him.

The exhausted Simanek was unhappy about the patrol, but Irene was a relatively peaceful area, so he looked forward to a quiet morning.

“I took an old Readers’ Digest and a can of precious beer in my big back pocket and thought I was really going to have a relaxing situation,” he said. “It didn’t turn out that way.”

Instead, Simanek and his squad ran into an ambush as they headed uphill. Mortars and gunfire from Chinese troops exploded around them. The machine gunner walking behind Simanek was killed, and the squad split up. Some ran for cover at the base of the hill while Simanek and the five other Marines in front of him jumped into a four-foot-deep trench near the top of the hill. One of them was shot through the chest, but things were about to get even worse.

Simanek soon saw two Chinese officers talking nearby. The Marine shot them both, but other Chinese troops threw grenades back in response. Simanek took shrapnel to his feet from one grenade, but he continued to try to draw Chinese fire away from the other Marines by popping up further down the trench. Eventually, however, two grenades came sailing into the trench. Simanek kicked one away, but he didn’t think there was enough time to kick away the second. Instead, he threw himself onto the grenade to absorb its blast and save his friends.

“It was training, it wasn’t any mental decision on my part at all,” he recalled. “It was an automatic thing pushed by somebody.”

Somehow, Simanek managed to cover the grenade with “the right part of my body that didn’t hurt me that much,” he said. Still, he’d taken a lot of shrapnel to his right hip and right lower leg and he was in immense pain.

But that did not stop him from fighting. He and the other Marines were pinned down by an enemy bunker slightly below them, so Simanek got on the radio and directed a nearby tank to fire on the bunker. The tank got it, but the struggle was not over. Simanek’s fellow Marines thought it was now safe to carry him down the hill, but the tank accidentally fired on them, wounding two Marines as it tried to kill some Chinese troops. The Marines could still move, but they could no longer carry Simanek, so he told them he would make his own way down the hill.

“The idea that they couldn’t carry me — it was no doubt the best thing to do for them to get going,” he recalled. “I certainly agreed with them.”

Now on his own, the Marine crawled back down the hill on his hands and knees until another squad found him and put him on an outbound helicopter. Nearly 70 years later, Simanek still remembers that helicopter ride.

“I enjoyed that helicopter ride so much. I just couldn’t get over how beautiful it was,” he said. “But then, I’d had a shot in the arm, and that sort of gave me a little extra sense of beauty.”

Simanek was treated for severe nerve damage in his right leg aboard the USS Haven in Japan. From there he was flown to Great Lakes, Illinois, where it took nearly a year for him to recover. The Marine was put on the disability retired list in March, 1953 and was discharged with a brace for walking. Seven months later, on Oct. 27, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower presented him with the Medal of Honor at a White House ceremony. Oddly enough, Simanek said Eisenhower was more interested in his German-speaking grandmother than in him.

“My grandmother who was from Germany had a very strong accent and President Eisenhower was more impressed with listening to her talk than he was with me,” he said with a smile. “He just enjoyed talking with her, listening to her accent.”

Simanek’s story is one of bravery, but in some ways it never ended.

“One of the hardest things about the medal is that you’re really not allowed to forget about it,” he said. “People will, in a good meaningful way, of trying to compliment you, bring about some memories that maybe you’d like to get rid of.”

After leaving the Marines, Simanek married, had a daughter, graduated from Michigan State University and worked in business before retiring in 1992. The Detroit native lives in Farmington Hills, Michigan, with his wife Nancy. He’ll turn 91 this year.

The ship that will be named after him is the second-to-last Expeditionary Mobile Base that the Navy plans to procure. As part of the Lewis B. Puller (named after the famous “Chesty” Puller of Marine Corps legend) class of ships, the USS Robert E. Simanek will have a flexible modular design capable of supporting “any mission you like,” as the commander of the USS Lewis B. Puller described his ship to Navy Times in 2017. Those missions include launching helicopters, small boats, unmanned surface vehicles, special operations or mine countermeasure operations; carrying troops or supplies; or performing maintenance.

“It’s a force enabler,” Brig. Gen. Francis Donovan, then-commander of Naval Amphibious Force Task Force 51/5th Marine Expeditionary Brigade told Navy Times. “It complements and enhances our capability.”

The ship class is an ideal one for Simanek, who saw his actions in the Korean War as a means of helping his unit accomplish their mission.

“Any sacrifices we really made were for each other,” he said. “We never thought about it as self-sacrifice so much as necessity to do your job so the group could succeed. It was our duty.”