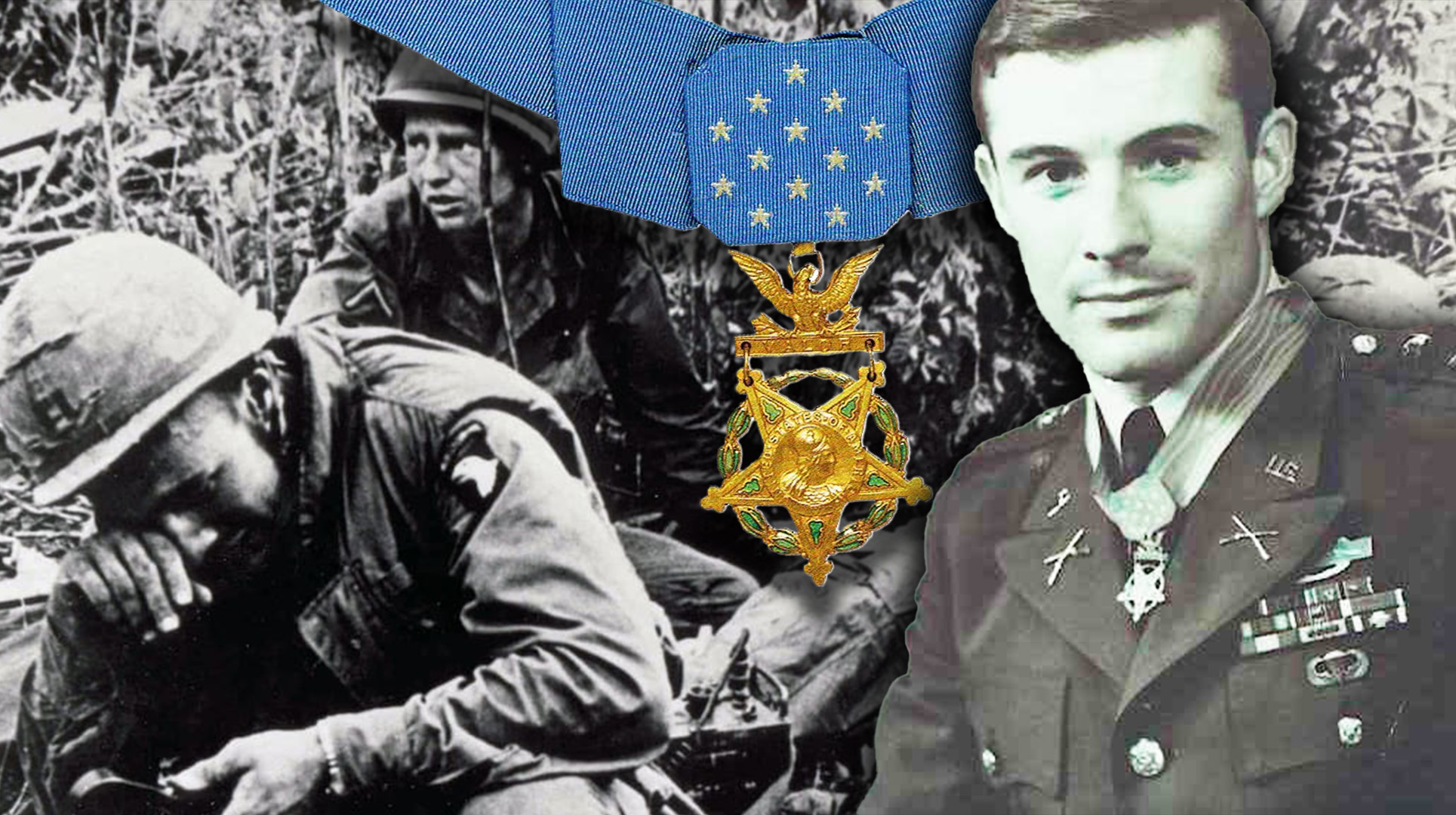

The “clerks and jerks” of Delta Company were surrounded and close to being overrun. As Capt. Paul Bucha, the company commander, dodged the machine gun fire from the trees overhead and constant explosions he began to wonder if his mother would ever learn the name of the unmarked grid coordinates where he was about to die.

But as he considered those dire thoughts, a young, untested replacement soldier, with no combat experience, ran to Bucha’s position through the hail of fire,

“This young kid who’d just joined us,” Bucha remembered in an interview. “I mean we were down with fire everywhere, and we were firing what little ammunition we had left because we were trying to conserve it. All hell was raining down on us.”

The soldier looked at the captain with, shockingly, a smile: “And he says, ‘Sir! We’re kicking the hell out of them, aren’t we!’,” Bucha said.

The captain laughed and replied: “Well, I guess we are.”

In fact, the battle raged on through the night of March 16, 1968. For hours, Bucha moved between his men, created diversions and feints to confuse the larger enemy force, called in artillery and gunship fire and loaded helicopters with wounded.

Ten of Bucha’s soldiers died, with nearly all emerging wounded. Over 150 North Vietnamese were killed in the battle, a toll nearly twice the number of Bucha’s entire company.

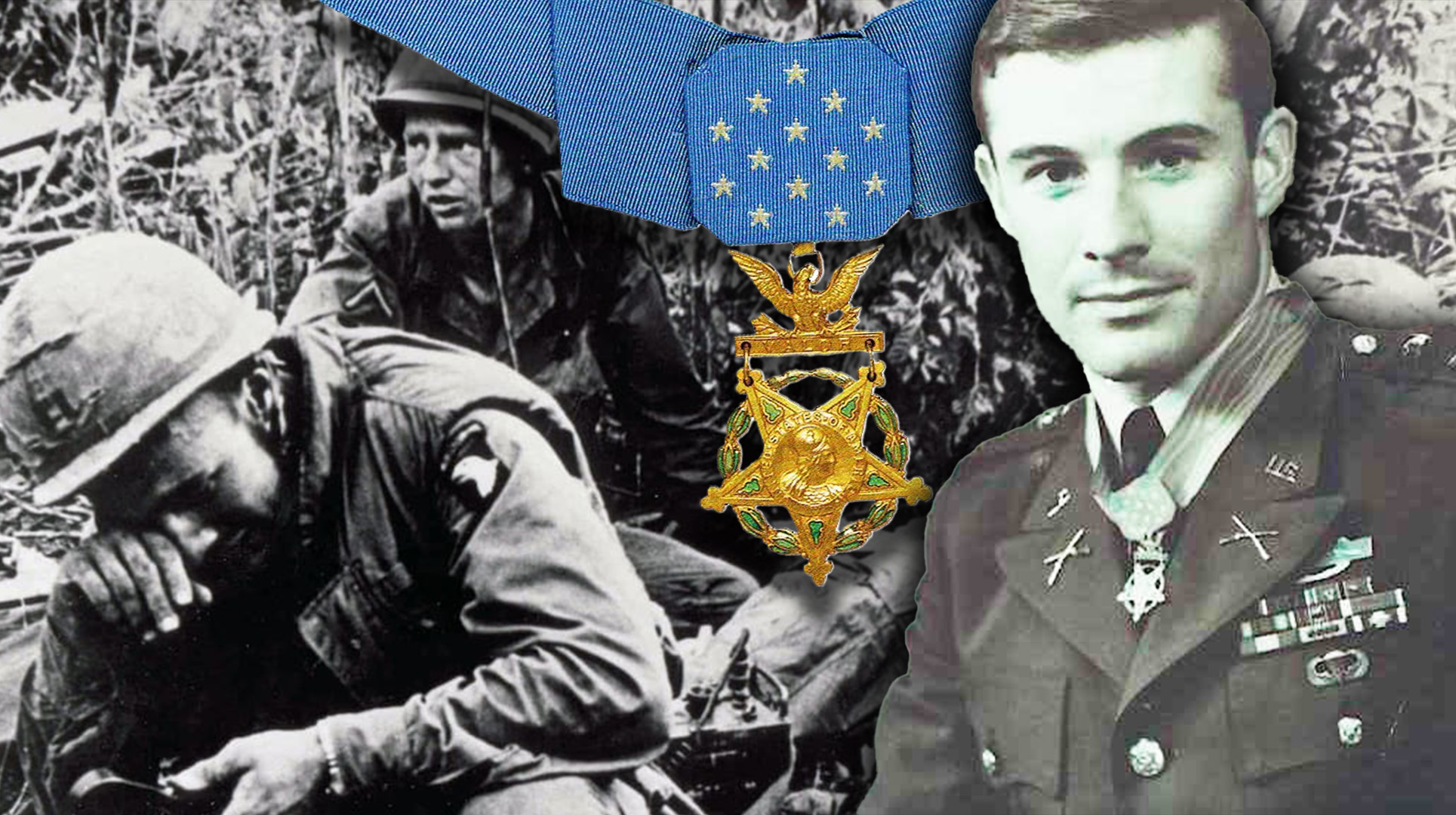

For his leadership and valor under fire, Bucha would be awarded the Medal of Honor.

Bucha, 80, died July 31 at his home in West Haven, Connecticut, where he lived most of his life. He was the state’s last living Medal of Honor recipient. With Bucha’s passing, 60 Medal of Honor recipients remain living.

The ‘clerks and jerks’

The son of a World War II veteran, Bucha was born in Washington D.C., and moved several times as an Army brat. For college, Bucha attended West Point, where he was an All-American swimmer. After graduate school at Stanford, he was sent to Vietnam as an infantry officer in the 101st Airborne’s 187th infantry regiment.

There, his battalion commander quickly promoted him to take over a newly formed company, delta. In an interview with the Congressional Medal of Honor Society available on YouTube, Bucha said he held formations, reported accountability and marched in pass and review for early-morning battalion formations.

It was just him, alone. Bucha had no soldiers assigned to him when he took command, at least at first. But the West Point honor graduate and rule follower to-a-T still performed his duties, even if the whole company — usually 100 or more men — was just him

“Delta Company, All present and accounted for,” he reported in the formations — meaning just him.

Then soldiers started to arrive, assigned by the battalion commander.

“He started filling me up with the rejects,” Bucha said. “We were called ‘the clerks and the jerks.’ I used to think, ‘my God, I have a few very, very smart guys and a lot of really mean guys. What a great group to go to war with.’”

Most had already seen combat and many were on a second tour of Vietnam.

“I said, ‘look if you have your choice of company commanders, you wouldn’t pick me’,” Bucha told his men. “But if I had my choice of soldiers, I’d pick you.”

The clerks and jerks of Delta Company were up to 89 men when they were inserted as 3rd battalion’s reconnaissance element near the village of Phuoc Vinh, with orders to patrol to contact. Soon after a resupply drop — in which the young combat newbie joined the company — the contact came.

“The whole mountain opened up,” Bucha said.

Taking machine gun fire from both elevated positions in trees and hardened positions, Bucha crawled 40 meters with grenades to take out a bunker, taking a shrapnel wound as he moved. Ordering a retreat to a defensive position, he realized an element was separated and cut off. Bucha ordered the men to, in the words of his Medal of Honor citation, “feign death and he directed artillery fire around them.”

As helicopters arrived to take out wounded, fire reached up from the trees toward the aircraft, which, Bucha said, “is the first sign that this isn’t a small unit.”

He ordered his men to throw grenades in series, calling to them two at a time to lob them to make their own numbers seem greater. “If they knew how small we were, we’d be finished,” Bucha said.

At daybreak, Bucha led a rescue party to recover the dead and wounded of the ambushed element.

Remembering every day

Bucha left the Army in 1972, working in business and with veterans support organizations. He served on the board of directors for the Congressional Medal of Honor Society as president from 1995 to 1999 and immediate past president from 1999 to 2001. Bucha unsuccessfully ran for Congress in 1993 as a Republican but maintained a strong interest in politics and served a foreign policy advisor for President Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign.

He is survived by his wife, Cynthia, and four children.

But in later interviews, he said the final morning patrol to recover the dead and wounded of his ‘clerks and jerks’ never left him.

“Next morning, we got everybody out and I saw my first KIAs that were my men,” Bucha said. “I remember thinking, I asked them to trust me. I promised I’d bring them home. And those 10 guys did, but I didn’t,” Bucha said. “And every day of my life I think back and wonder what could I have done better to bring those 10 home?”