More than 70 years ago, Lieutenant John R. Fox was penned in on the second-floor of a building in an Italian village. German soldiers had overrun the town just before Christmas, 1944, leaving Fox and a few other forward observers as the only Americans left. Over the radio he was directing an artillery strike that put several Nazis but also Fox himself in the crosshairs.

“That was just where I wanted it. Bring it 60 yards!” he told artillery soldiers.

Fox’s decision in the village of Sommocolonia, Italy would help turn the tide of the fight, at the cost of his life. He would eventually receive the Medal of Honor for his heroism, but only five decades later, his service was ignored due to the racism of the time.

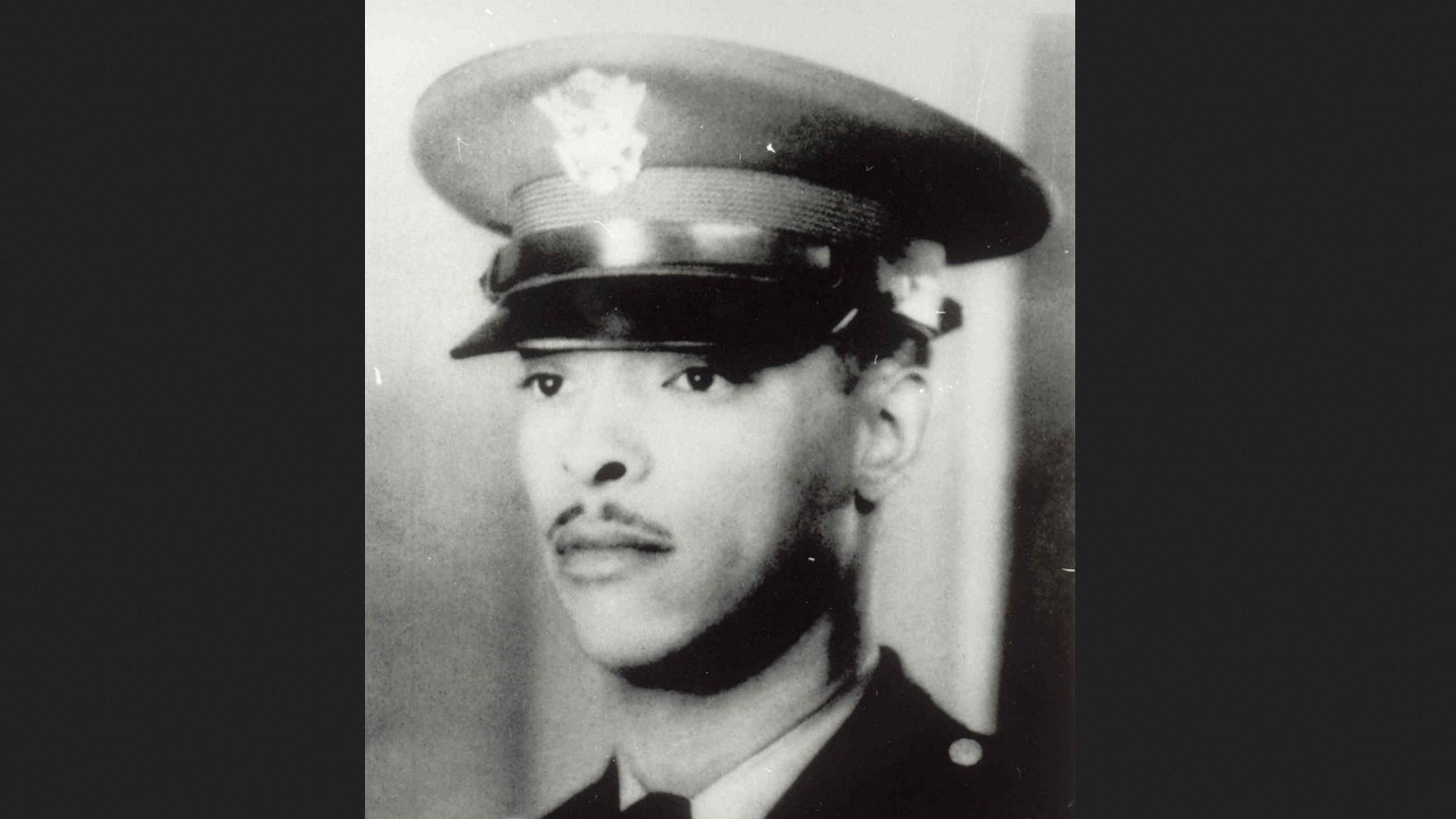

John R. Fox was born in 1915 in Cincinnati, Ohio. He studied at Wilberforce University in Ohio, a historic Black university. While there, he joined the ROTC program, which at the time was run by Aaron Fisher, a Black World War I veteran who had earned the Distinguished Service Cross for his time in France. Fox graduated, commissioned a second lieutenant and was assigned to the 366th Infantry Regiment. This was in the days of a segregated military, and the 366th was an all-Black unit. He also started training in artillery.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news and culture in your inbox daily.

Eventually in 1944 the 366th was deployed to Europe. Fox and others were assigned to the all-Black 598th Field Artillery Battalion, another segregated unit. It was December, and Fox volunteered for a Christmas posting in an observation space in Sommocolonia, which the Allies had just taken from the German Wehrmacht. However the Germans quickly retook the town, using the holiday and disguised soldiers as cover to get into Sommocolonia, then unleashed heavy artillery that forced the American forces back.

That is, except for Fox and some of his fellow soldiers. They stayed in the second floor of the Italian building, where he could track German movements and call in counter artillery strikes. But the Germans kept pressing in, so Fox kept calling for attacks closer to his position, eventually 60 yards from where he was.

The commander of the 598th directly called Fox, asking for confirmation. Fox didn’t waiver. He confirmed he wanted the artillery strike launched.

“The last communication from Lieutenant Fox was, ‘Fire It! There’s more of them than there are of us. Give them hell!’” his Medal of Honor citation noted.

After a week of fighting, the American forces retook Sommocolonia. Fox’s body was found, surrounded by 100 dead German soldiers, according to witnesses. Fox’s remains were returned to his wife, and he was buried in Colebrook Cemetery in Whitman, Massachusetts. He was 29.

Despite his sacrifice and fearlessness in the face of danger, Fox’s heroism would be ignored for years. It wasn’t until 1982 that he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. In the 1990s, the Department of Defense opened an investigation into why no African-American service member had received the Medal of Honor for fighting in World War II, concluding that the virulent racism of the time was the reason. The Department of Defense set about rectifying that, with seven people identified for the Medal of Honor. For his sacrifice to stop a German advance, John R. Fox was awarded with the highest military honor on Jan. 13, 1997, 52 years after his death.

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty: First Lieutenant John R. Fox distinguished himself by extraordinary heroism at the risk of his own life on 26 December 1944 in the Serchio River Valley Sector, in the vicinity of Sommocolonia, Italy,” the Medal of Honor citation read.

Fox is one of 94 African-American Medal of Honor recipients.

In 2021, Fort Sill rededicated a building onsite after the late soldier; the new Fox Hall was announced as the headquarters for the 1st Battalion, 22nd Field Artillery.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Is Ukraine winning the war against Russia?

- Air Force sends F-22s to Middle East to deter aggressive Russian pilots

- Army secretary concerned ‘woke military’ criticism could hurt the service

- Fort Sill commander fired amid investigation

- Fort Polk is renamed Fort Johnson