When traitorous slaveholders led a rebellion in 1861 and attempted to throttle America’s young democracy, the Grand Army of the Republic had a secret weapon to crush the insurrectionists: Coffee.

For soldiers in the Union army, coffee was not only their preferred drink but the lifeblood of freedom’s fighting force.

While it’s possible that American soldiers received coffee in their rations before 1861, the war clearly marked a turning point. The Army’s 1858 Quartermaster Manual made no reference to coffee — and hardly mentioned rations — but the 1863 Quartermaster Guide outlined how coffee should be transported along with other freight and it included coffee in regular ration tables, said Elijah Palmer, the acting Quartermaster Museum curator and education specialist

at the Fort Lee Army Museum Enterprise in Virginia.

Civil War veteran John D. Billings, who served in the 10th Massachusetts Battery, wrote in his memoir Hardtack and Coffee about how important the coffee ration was to the average Union soldier.

“When tired and foot-sore, he would drop out of the marching column, build his little campfire, cook his mess of coffee, take a nap behind the nearest shelter, and, when he woke, hurry on to overtake his company,” Billings wrote. “Such men were sometimes called stragglers; but it could, obviously, have no offensive meaning when applied to them. Tea was served so rarely that it does not merit any particular description. In the latter part of the war, it was rarely seen outside of hospitals.”

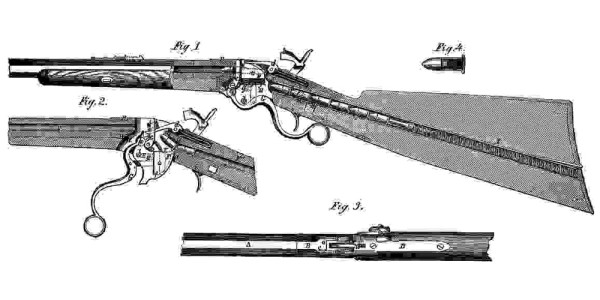

Union soldiers were issued 36 pounds of coffee each year and would crush coffee beans with their rifle butts or the handles for their bayonets, according to Jon Grinspan, curator of political history at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Some carbines came with coffee grinders built in their stocks, but they were not widely used.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

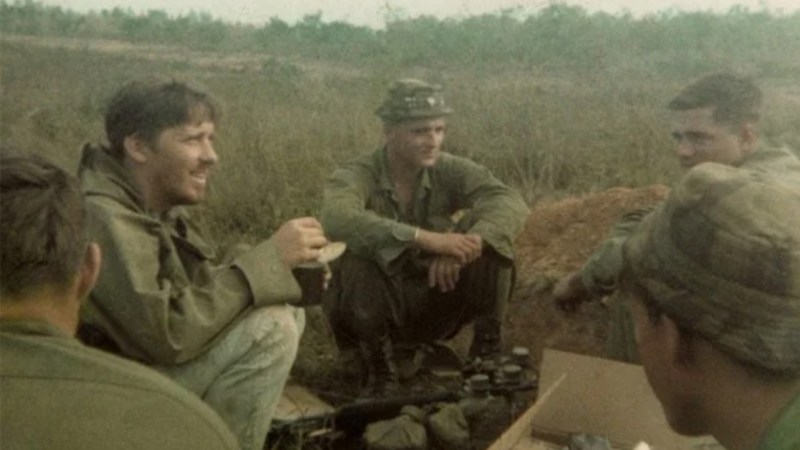

“This wasn’t filtered, drip coffee,” Ginspan told Task & Purpose. “This was kind of closer to what we think of as Turkish coffee, where you cook it in a pot and the grounds have settled in the bottom. Sometimes they would filter it through a piece of cloth or something like that. They’re cooking it over these tiny fires. In the Navy, there are all these steam vents on the ships, and they’re heating their coffee in the steam vents.’

When the Union army traveled far away from its logistics staging areas, such as when Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman was on the march in Georgia, troops would use fence rails and anything else they could find to build fires for brewing coffee, Ginspan said.

There’s no doubt that Union soldiers were passionate about their coffee, but it is unclear whether the caffeine improved their combat performance.

“The Union general who made the most stress on caffeine and coffee was Benjamin Butler — one of the worst generals of the war,” Grinspan said. “And then you have some commanders who do astounding things when they have no supplies at all.”

But coffee certainly contributed to the well-being of Union soldiers, Grinspan said: When he read letters and diaries from the Civil War for his research, he realized that troops talked more about coffee than any other subject.

“You read their letters and they talk about coffee all the time,” Grinspan said. “It’s the one constant. It’s the one consolation in what’s otherwise an incredibly hard experience. It’s throughout so many letters and so many diaries that it’s ubiquitous and almost unnoticed because it’s so prevalent and so important.”

To put that into perspective, Union soldiers during the Civil War may have written home about coffee almost as often as U.S. troops told friends and family how hot Iraq and Afghanistan was more than a century later.

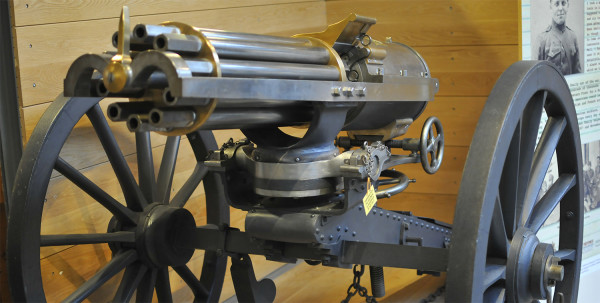

In addition to its larger population and industrial capacity, coffee was one of the advantages that the North had over the South during the Civil War. It was much more difficult for Confederate troops to get coffee because it was imported from Brazil at the time and the Union navy was blockading the South, he said. Ironically, Brazil did not abolish slavery until after the American Civil War, so Union soldiers were issued coffee beans grown by slaves.

The Civil War marked the start of a beautiful friendship between U.S. service members and coffee that continues to flourish to this day. An estimated $94 million worth of coffee was delivered to the military in fiscal 2022, said Michelle McCaskill, a spokeswoman for the Defense Logistics Agency.

The latest generation of Meals Ready to Eat has a total of 24 different menus, 13 of which come with packets that contain instant coffee, sugar or a sugar substitute, and creamer, said David Accetta, a spokesman for the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Soldier Center.

However, surveys have shown that U.S. service members are drinking less coffee because other types of beverages are now available, Accetta told Task & Purpose.

“The Combat Feeding Division responded by developing other additions to the different rations that included caffeine for mental alertness,” Accetta said.

Still, coffee will always hold the distinction of being the caffeinated beverage that helped end slavery in the United States and restore our union. The next time coffee drips onto your dress uniform, don’t you dare take it to the cleaners: Those are the stains of freedom.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- ‘Untethered’ Air Force general: ‘When you kill your enemy, every part of your life is better’

- The Air Force’s top recruiter is personally reviewing recruits’ hand tattoos so they can enlist

- Political candidate accused of stolen valor claims his deployments are ‘classified’

- Tank warfare is still relevant, even if the Russians suck at it

- The best military field gear we’ve ever bought

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.