Amid Russia’s staggering losses of tanks in Ukraine, some military experts are arguing that the tank cannot survive on modern battlefields when pitted against drones, loitering munitions, and anti-tank missiles.

According to some U.S. military leaders, Russia’s ill-fated invasion of Ukraine seems to validate the Marine Corps’ impetus to retire its armored battalions as part of its sweeping new force design plan.

“Why would I want a tank, when I can kill a tank with a loitering [drone] munition?” Marine Corps Maj. Gen. Francis L. Donovan, commander of the 2nd Marine Division, told the Washington Post in January.

However, Russia’s disastrous losses in Ukraine do not mean that tank warfare will soon be a thing of the past. In fact, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has scolded Germany for not providing his country with tanks, telling the German newspaper Bild in a recent interview: “For us, tanks mean that we can rescue more human lives. Armored engineering is a question of survival, the survival of our soldiers.”

For more than 100 years, armies all over the world have used tanks to smash through defensive positions and destroy enemy formations. During World War II, the Soviets used tanks to charge through German lines and isolate large pockets of enemy troops. Since then, tanks played major roles in Israel’s 1967 and 1973 wars as well as the U.S. military’s operations in Kuwait and later Iraq. The tank is the backbone of modern militaries, an armored juggernaut that has defined the battlefield for decades.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, however, has shown how vulnerable tanks are to modern defenses, especially if they are not used correctly. When Russia launched its full-scale attack in late February, it discarded traditional tank doctrine and tactics, according to retired Marine Col. J.D. Williams, a defense policy researcher with the RAND Corporation. For example, when tanks are sent into battle, they need to be supported by infantry and artillery units to suppress enemy anti-tank weapons, he said.

“Well, the Russians didn’t do that,” Williams told Task & Purpose. “They basically sent their tanks without adequate artillery, with very limited infantry, and they got their ass handed to them in a number of places.”

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

The Russians likely did not expect the fierce resistance they faced in Ukraine, Williams said. Ukraine also has terrain that is very difficult for tanks to operate in. These factors have contributed to Russia’s losses, which the open-source database Oryx puts at more than 1,000 tanks.

With that said, the war in Ukraine is the largest conflict in Europe since World War II, and the same open-source database indicates the Ukrainians have lost roughly 300 tanks, Williams said. The Ukrainians have replaced some of their losses thanks to military assistance from other countries and augmented their existing force with captured Russian tanks. To put the Russian and Ukrainian losses into perspective, U.S. military planners during the Cold War expected that thousands of tanks and armored vehicles would have been quickly destroyed if a war had broken out with the Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces, he said.

As for what the war in Ukraine shows about the future of tanks on the battlefield, Williams cautioned that militaries first need to study the conflict to come up with the appropriate lessons.

“They’re going to have to go a couple layers deeper than simply ‘the Russians lost 1,000 and the Ukrainians did better on the battlefield’ to understand what are the factors, the drivers, the causes behind that,” Williams said.

To be successful, any evaluation of what the Ukraine war portends for the future of armored warfare should include a rethinking of how tanks are designed in the age of modern anti-tank missiles and other defenses, he said. For example, an Army unit in Europe recently fielded the Israeli-made Trophy Active Protection System, which is built to intercept and destroy anti-tank missiles.

“Tank design since the end of World War II has really been driven to make tanks bigger, more complicated, more expensive,” Williams said. “And anytime there’s an anti-tank evolution, the response is to add something to the tank to defeat that. It appears that the cost-benefit — the relative cost of defeating a tank vs. what a tank costs — is going against the tank.”

Williams added that one of his colleagues at RAND, retired Army Col. David Johnson, has argued that warfare is now being defined by defensive weapons and fortifications again, as it was during the trench warfare of World War I.

“The tank was developed, in part, to defeat that; and maybe things have come full circle,” Williams said. “But there’s still a need for some type of Mobile Protected Firepower to achieve decisive results at critical points on the battlefield. The question is: Is the tank going to do that in the future? Are there alternatives?”

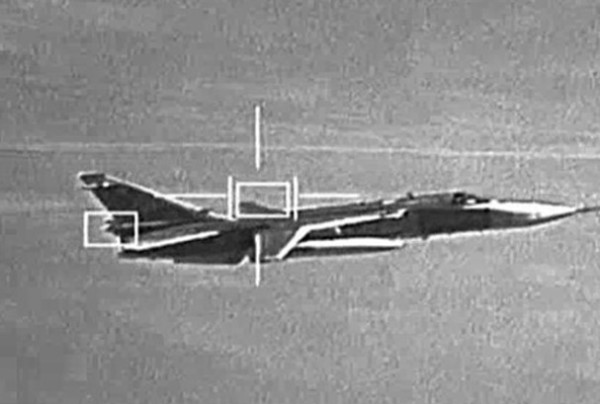

“Ubiquitous surveillance coupled with swarming unmanned systems; that seems to be something that kind of happened in the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over the Nagorno-Karabakh recently, where armored vehicles took a lot of hits from those kinds of weapons systems,” he added. Maybe that’s an alternative to a tank to achieve that.”

Armored warfare has had to adapt to new technologies in the past, such as during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, when Israeli tanks proved to be vulnerable to Egyptian anti-tank missiles, said retired Army. Maj. Gen. William L. Nash, who led the 1st Armored Division when it deployed to Bosnia. In that case, the Israelis learned to use artillery and infantry to protect their tanks.

With the threat that drones now pose to tanks, it is vital that armored units come equipped with anti-drone countermeasures, Nash told Task & Purpose. Tanks are particularly susceptible to drone attacks when they are not moving, he added.

Going forward, Nash believes that tanks will still have a role on the battlefield, but they must be part of a wider array of combined arms units — such as infantry, artillery, airpower, cavalry scouts, and unnamed aerial systems — that are equipped with the latest weaponry.

“I’m a proponent of mobile armored warfare, but not a zealot for the tank,” Nash said. “Mobile armored warfare is, by definition, combined arms. As technology has evolved, combined arms includes a lot more things. It includes drones and look-down/shoot-down technology. It includes things cyber that can be multipliers for the combat power of the combined arms team both in an offensive or defensive way.”

The U.S. Army Armor School is currently helping to review how tank crews can counter any enemy electromagnetic, drone, and cyber attacks, said Maj. Andrew Harshbarger a spokesman for U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command.

The school has also developed a strategy for how the Army’s armored units can improve their lethality, and survivability, and sustainability in large-scale combat operations in austere environments, Harshbarger told Task & Purpose.

“When it comes to training, we continue to modify instruction at every echelon as we learn from the conflicts in Nagorno Karabakh and Ukraine,” Harshbarger said. “These wars continue to reinforce the importance of combined arms maneuver and the need for joint operations to set conditions for tactical engagements. We ensure that our leaders and soldiers understand how to fight as a combined arms and joint team, as well as the need to present multiple dilemmas to our enemies at echelon.”

Ultimately, one of the major lessons from the Ukraine war may end up being not just that the tank is far from dead, but that it needs a lot more protection to avoid becoming too big and vulnerable to survive modern wars, like the battleship. And while it’s clear that the tank must evolve to survive against modern weapons, it’s unclear what, exactly, the tanks of the future might look like — and what next-generation weapons they might need to punch through enemy defenses.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Meet the best-trained team of divers in the Army

- These are the best (and most absurd) unit patches in the US military

- What the military’s ‘missing man table’ is and what it means

- Sailors swindled out of thousands of dollars in Tinder scam

- Someone turned a Peugeot convertible into a battle buggy in Ukraine

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.