Kyle Carpenter doesn’t remember what he was thinking before he jumped on top of a Taliban grenade to save his friend’s life, but he believes that you were worth sacrificing for.

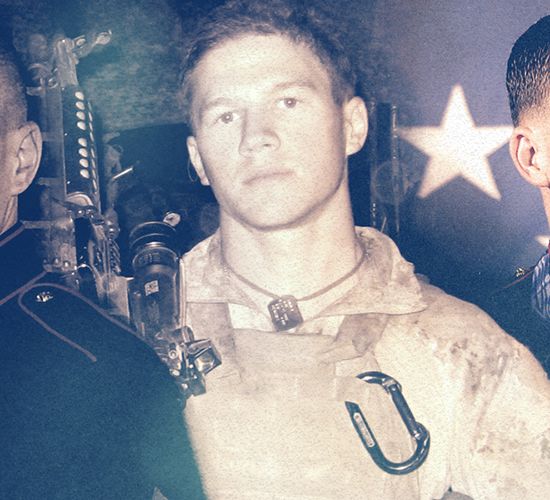

On Nov. 21, 2010, then-Lance Cpl. Carpenter was manning a rooftop security post on his first deployment to the volatile Helmand Province in Afghanistan when a hand grenade landed near him and his friend, Lance Cpl. Nick Eufrazio. Without hesitation, his award citation for the Medal of Honor says, Carpenter jumped on the deadly explosive and took the brunt of the blast, which ripped through his face and arm with white hot shrapnel.

Badly burned and knocked out, Carpenter flat-lined numerous times after his injury, but miraculously, woke up weeks later in a hospital, minus his right eye and with the much of his body mangled. He endured nearly 40 surgeries and spent almost three years in the hospital recovering, where he had to relearn the basics like walking and tying his shoes.

Now 29, Carpenter is a recipient of the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for combat bravery. He’s gone on to graduate from college, run a marathon, go sky-diving, and now, he’s authored a memoir — released on Tuesday — that he hopes will inspire people to live a good life despite whatever challenges they might face.

“I wrote the book to help people,” Carpenter said in a recent phone interview with Task & Purpose. “I wrote it to show people that you can come back better and stronger. You can make it and you can get through it. Not only can you get through it, but you can come out on the other side smiling.”

The memoir, which was co-written with Don Yaeger and titled You Are Worth It: Building A Life Worth Fighting For, starts off with Carpenter hearing a phrase so many vets hear nowadays: “Thank you for your service.”

That well-meaning “thank you” was from his Uber driver, Bobby, on the way to the airport. As he explains in the book, Carpenter usually just responds with thank you very much, I really appreciate that. But instead, for some reason, Carpenter responded: “You’re worth it.” It felt awkward the first time he said it, but it’s something he says more regularly now.

“When Bobby told me ‘thank you for service’ and I responded ‘you are worth it,’ he looked at me in the rearview mirror for a while and he told me, my parents brought me here when I was very young from Pakistan. I’ll never experience the hardships they had faced. I got an amazing education. And I’m so thankful to live in what I feel like is the greatest country in the world.

“So when I got out of that Uber ride, I really reflected on that moment and I wanted him to know that his family, the hardships that they faced. They are worth it.”

Task & Purpose: I tend to roll my eyes internally when I hear thank you for your service. It just seems like it’s not the beginning of a conversation. It’s just checking the box.

Kyle Carpenter: Exactly.

In the book, you say thank you so much, I really appreciate that. I read that and I thought, he’s so right.

I’m super pumped [Laughs]. One person at least took one thing from the book, so that’s a great start.

There’s a bit of a divide among veterans about what you say in response. I think you are totally fine with that, just expressing your appreciation of the sentiment.

I can understand where both sides are coming from. But on the positive side, if those people didn’t say anything and if you never got told that…I feel like every veteran, no matter how hard you eye roll at it, would much rather have that instead of civilians not being nice at all. Thankfully, we’ve come so far from the days of Vietnam when veterans coming home were spit on or protested at airports.

It’s on us veterans to capitalize on those moments, and maybe continue the discussion, or just be appreciative when that moment is happening.

Many service members have trouble getting out and trying to fit into the civilian world and properly transition. What’s it been like for you, getting out of the Marine Corps?

This is one of the parts of my journey where I kind of cringe, and I hate that I can’t truly relate to a veteran that did their four years and got out. I didn’t have a ‘normal’ transition.

One of the positives about spending three years in a hospital is I had time to truly think about and reflect not only on where I’d been and what I’d made it through, but where I was going.

In between all the surgeries and therapy, I really took time to think about my life. I’d only been in the Marine Corps for about a year and a half before I was injured. And I joined because I wanted to commit myself — whether it was four years or 20 years — to a greater purpose than myself.

After my recovery, it was inevitable that I’d have to choose: do I want to get out and ‘hang the uniform up’ or do I want to stay in?

I felt like I had accomplished what I had set out to do. Maybe I had only been in a year and a half, but bleeding for my country the way I did, I felt like I had contributed, and done my part, not only for the Marine Corps, but for our country, and to try to help people around the world.

Also knowing that being as wounded as I was, spending as much time in the hospital that I did, making the relationships with my fellow wounded warriors, the hospital staff, the nonprofits that are at Walter Reed. I felt like if I wanted it to continue I would always have that connection whether I got out of the military or not.

I was comfortable getting out, and I used my time at Walter Reed to do admissions paperwork for school, and that was going to be my priority and that was going to be my new mission.

Even though I can’t relate to just getting my DD214 and kind of ‘peacing out,’ I still had to get out after three years at the hospital, driving straight from the gate at Walter Reed into my one-bedroom apartment in Columbia [South Carolina] two weeks before starting my freshman year of college. And I still had to make that step, and try to stay positive and make the most out of this new experience, and figure out what exactly this new body and this new life of mine was going to mean for the rest of my life, outside of a hospital.

So just speaking on transition — and maybe something all vets can relate to — it’s okay if it takes you a little while to feel like you’re fully transitioned. And yes it’s inevitable you are going to hear the ‘thank you for your service’ line, and there will be really frustrating questions from the public.

If I had a dollar for every time I got asked, ‘oh, you’re the Purple Heart winner!’ One, obviously, I’m not a winner. And two, I know you’re referring to the Medal of Honor, which tells me that you have no idea what the difference is between the two.

But everything is a lens and how you choose to look at it and the perspective that you want to bring.

I realized those questions were going to continue every day I was at school. But when they came, that was an opportunity to educate those people. It doesn’t bother me near as much as the veterans who say, ‘screw civilians, they don’t know anything.’

They’re complaining instead of connecting with someone and explaining the military. From that moment on, for the rest of their life, they will never make that mistake to another veteran.

So I just look at it as an opportunity to educate. And just knowing that everybody… you can’t expect everyone to have the same experiences. Not everyone is a combat-hardened Marine, and not everyone has earned the Purple Heart. You can’t expect that from everyone.

Just think about the times you got through, like when you were on a painful hike. Or a night of being completely frozen and not feeling your fingers out in the middle of the woods. Sitting in a fighting hole, getting rained on in February.

It’s hard leaving what you’ve known for a significant portion of your life, and leaving that bond that 99% of the public doesn’t understand. Just know it’s going to be a process. And know it’s going to be slow at times.

But there are people that care about you. There are veterans that will always be there that you served with. And people get it. You gotta pick up the phone and call your buddies or someone. Just know that it’s going to be a process.

Use those moments when you’re going to get frustrated with things to better yourself and to be an example to all of those who don’t have the privilege to wear the cloth of the nation.

There’s a part in the book where you describe a senior Marine coming up to you at the Marine Corps Birthday Ball, and he tells you that you were the reason he hadn’t killed himself. It’s such a powerful moment, and I wonder if you can talk more about that, and I wonder if there are any other times when people have come up to you and left you speechless?

I’m so glad you brought that up. That was one of the most impactful moments for me.

He was a decorated Marine of much higher rank. He comes up to me and he tells me that if I can get up every day and put a smile on my face with everything that I’ve went through, he can do it too. I was completely floored.

I’m so thankful it happened and I made him promise that I’d see him again next year. It was such a light bulb moment: no matter what our rank, no matter where we come from, no matter who we are, we all struggle.

And that led to me realizing that even though he was a higher rank and we came from different places, we both had struggled — mentally, physically, or emotionally. Struggle is the one thing that everyone on this earth can relate to.

With this book, I wanted something that anyone could pick up. From a CEO to a homeless person, I wanted something that anyone can pick up and take lessons from.

The second piece of that is that almost every single person and veteran that comes up to me… If they’re a veteran, they say ‘well, I was never in combat, or I never did anything like you.’ And people that have never served in the military will say, ‘oh well, I was never in the military and I don’t think I could ever do what you did.’

What I would tell everyone — veterans, service members, civilians — I urge you to never compare your struggle with anyone else’s. Just like the Marine who approached me and told me he didn’t kill himself because of me. Or the lady that came up to me and said, ‘I have terrible arthritis and I can barely get out of bed in the morning, but I never did anything like you.’

We all have our own struggles. We all have our own journeys. And you’re doing yourself a serious injustice by comparing yourself with someone else. It’s not a competition.

Even if someone seems like they’ve been through way worse than you — and even if they have — don’t compare. It’s okay. You’re living your life, you’re doing your thing. Just learn from that, become better from it, and stronger from it.

It’s something we see often in the vet community. There’s this tendency where someone will denigrate someone else because they weren’t in combat. Or maybe, it’s like, oh, you’re a POG and I’m a grunt.

I hate it. Yes. I hate it.

Or like, I have a combat action ribbon. Okay, I jumped on a grenade and received the Medal of Honor but that is because I was put in a very unique situation that very rarely ever happens.

Let’s say you were a logistics officer. You helped get me the supplies that my buddies needed and my corpsman needed to stop my bleeding, to keep me alive, to get me here today. To see my family again. To impact people and try to help and spread positivity throughout the world.

So because you don’t have a CAR and you didn’t get shot at, your job as that crucial logistics officer, or even as a freakin’ water purification specialist is somehow worth less? I had to stay hydrated to make it through that deployment and survive, and help those people of Afghanistan.

Your job is less important just because you weren’t in a position to get shot at? That’s the most ridiculous thing I have ever heard.

And if you do act like that to your fellow service members or veterans — they walked into a recruiting station and raised their right hand to give up to their life for this country, just like you. You didn’t do any more or any less.

Shame on you.

We’re all on the same team. We’re all trying to accomplish the same mission. And we’re all there suffering and going through it — maybe in different capacities — but we’re all going through it together.

So if you don’t have a CAR, be proud of what you do and what you contribute to those that do. But if you do, big deal. Go find the next guy that’s been shot at 100 times. It’s incredible that you did that, and our nation and me specifically are forever grateful, but not everyone can be in the infantry. Not everyone can go out and run and gun all day long.

And some of the most impactful Marines and mentors, and some of the greatest Marines that took care of me and helped comfort my family and look after me during my three years at Walter Reed…my best friend and the Marine that looked out for me the most and mentored me the best…he’s one of the few people in my life that truly impacted me on a daily basis. He’s an air winger.

You’re either infantry or you’re supporting the infantry. And if you’re supporting me, be proud of that. If you’re infantry, be thankful for that. Don’t put people down for that.

I’d like to go back to your action for the Medal of Honor. It’s incredible what you did. And the thing that I’m curious about is that you’re hailed as a hero and you don’t even remember doing it, right? You can’t even tell your own story. That’s got to be really strange.

Yeah it’s very strange. And in the beginning, I was frustrated even before the two-year investigation. Even before all of that, before people were grilling me with questions and wondering what I remembered and what I didn’t.

There were years of my life being investigated for something that I can’t even remember, or I didn’t even really know what happened. Even before that I was frustrated when I tried to think and I couldn’t remember.

But I realized how stupid it was to have that mindset. Even though I couldn’t remember, I woke up. And I’m still alive.

Nobody is holding it against me. And I shouldn’t expect to remember all the pieces and parts of what occurred on the roof that day when I got hit and injured and my body and mind — from my head to my ankles — got completely torn apart. I didn’t wake up for five weeks. So now I understand. It’s okay that I don’t remember everything.

Now I just try to look at the positive. I might not remember, but I’m here. I’m still kicking, and I’m so very thankful for that.

I hope you’ll indulge me but I wanted to ask a few sort of ‘rapid fire’ questions.

Yeah.

Like, only a Marine veteran would ask these kinds of questions. Probably not other journalists.

Uh oh.

And there are some vets on Twitter who gave me some suggestions. So everybody wants to know what is your favorite MRE?

Well, I’m gonna say I’m a little upset that there’s a pizza one now. But I was definitely a cheese tortellini guy .

And the other one people wanted to know is peanut butter or jalapeño cheese? If you can settle this debate, I’d really appreciate it.

Anything spicy or super flavorful like that, I am all about. So sorry to anyone that doesn’t agree, but definitely the jalapeño.

That’s okay, you’re totally right. Do you have a favorite Terminal Lance strip?

Oh man.

I’m not even answering this because I don’t know. I am genuinely telling you that Max [Uriarte] is a genius and he just creates amazingness. So there’s no way that I could choose my favorite Terminal Lance strip. But just know that I am a supporter and any time, anywhere, I’ll throw up the Terminal Lance symbol.

Ok, a couple more: Is the A-10 the best close air support platform or the greatest close air support platform?

Wait, what was the first option?

[Laughs] Is the A-10 the best CAS platform or the greatest CAS platform? I’m basically just trying to get you to say the A-10 is the greatest thing in the world, but you don’t really need to agree with me.

Well I had a couple of Warthogs fly over my head in some intense firefights and I would just say that they performed beyond beautifully, and I was so thankful to look up and see them flying just a few feet overhead and seeing that nice sexy payload on the bottom of it.

So absolutely the greatest, because if I didn’t have those A-10s, we might not be having this conversation right now.

You’re probably not the only vet who would say that. Now, I have one other question that I’m hesitant to ask but I have to. So, this was your first deployment in Afghanistan, right?

Correct.

So in Marine Corps parlance, you were considered a quote-unquote boot , and I’m just wondering…

Oh yeah.

You probably keep in contact with your senior Marines still. I do, too. Can they still call you a boot, or now that you have the Medal of Honor, will they not even go there?

Yeah, right! They rag on me now harder than ever. The Medal of Honor, I promise you, does not make you safe from any Marines that you knew before it happened. If anything, it only opens the door for way more shit-talking to occur, so I promise you I’m not getting any easy treatment from buddies prior to everything that happened.

Well Kyle, thank you so much for this interview and more importantly, thank you for everything that you’ve done and continue to do. You’re an inspiration and I really appreciate it.

Hey man, you’re worth it.

You can learn more about Kyle’s new book here >

Editor’s note: This interview was edited for length and clarity.