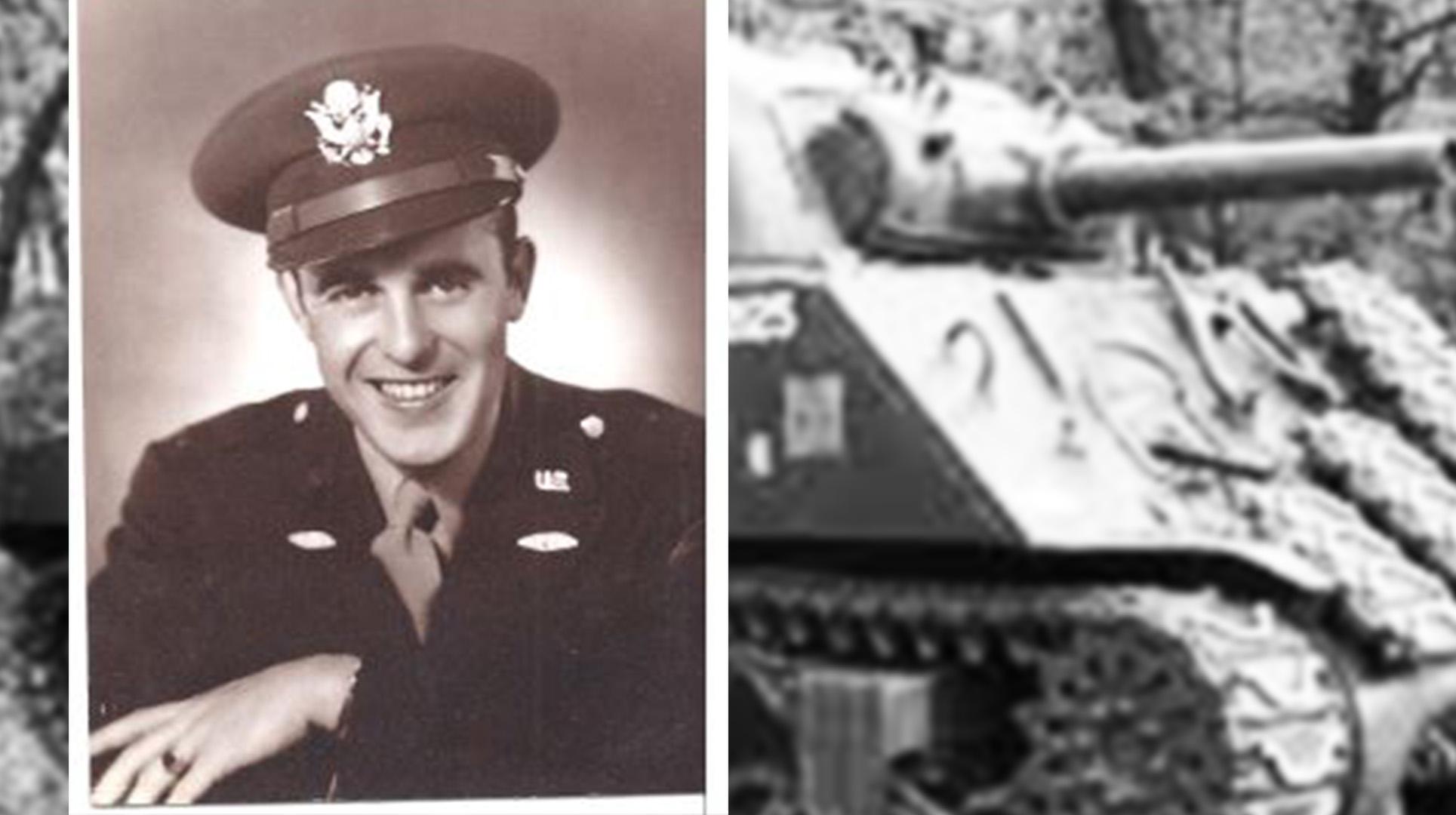

Anne Collingwood came into the world without a father. Army 2nd Lt. Gene F. Walker, a World War II tank commander, died in battle while pushing into Germany alongside General George S. Patton’s army.

Collingwood was born in September 1944. Walker, her father, died that November.

“They even wonder if he received word that I had been born or any kind of picture or anything because nobody knows that,” Collingwood, 79, told Task & Purpose. “Unfortunately, he and I didn’t cross paths.”

Last summer, Collingwood received a call from the Army to tell her that Walker’s remains had been identified by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, the latest in the 72,000 unidentified American troops that the agency is working to put names and faces to.

“I had no idea about it until I think I got a call in July that his remains had been identified,” Collingwood said. “I almost passed out. I couldn’t believe it. Seriously, it was just more than I could imagine.”

Over the last week, the DPAA announced the identification of remains belonging to two soldiers and an airman who served in the U.S. military during WWII. In addition to Walker, the DPAA recently identified Army Air Force Staff Sgt. Franklin P. Hall, 21, of Leesburg, Florida; and Army Sgt. George F. Bishop, 22, of Centralia, Washington.

The troops were three of the 81,000 American troops still missing from conflicts dating back to WWII. Although about half of that total were lost at sea on sunken ships or plane crashes, officials still think nearly as many might one day be found on former battlefields. Approximately 75% of missing troops were lost in the Indo-Pacific region.

According to Ian Spurgeon, the DPAA’s regional historian, there are approximately 1,000 ground losses unaccounted for in Germany. Of those, 67 have been identified which includes Lt. Walker.

“Our historians in our Europe-Mediterranean directorate are in the midst of a long research and recovery project focused on finding the American soldiers that are still missing from ground combat along that western border of Germany,” said Sean Everette, a spokesperson for DPAA.

Collingwood didn’t know a lot about her father because her mother and grandmother didn’t share much. She assumed it was too hard for them to talk about. When Army officials visited Collingwood’s house in Solana Beach, California, they gave her a book of information about her father’s military history and the battle where he died.

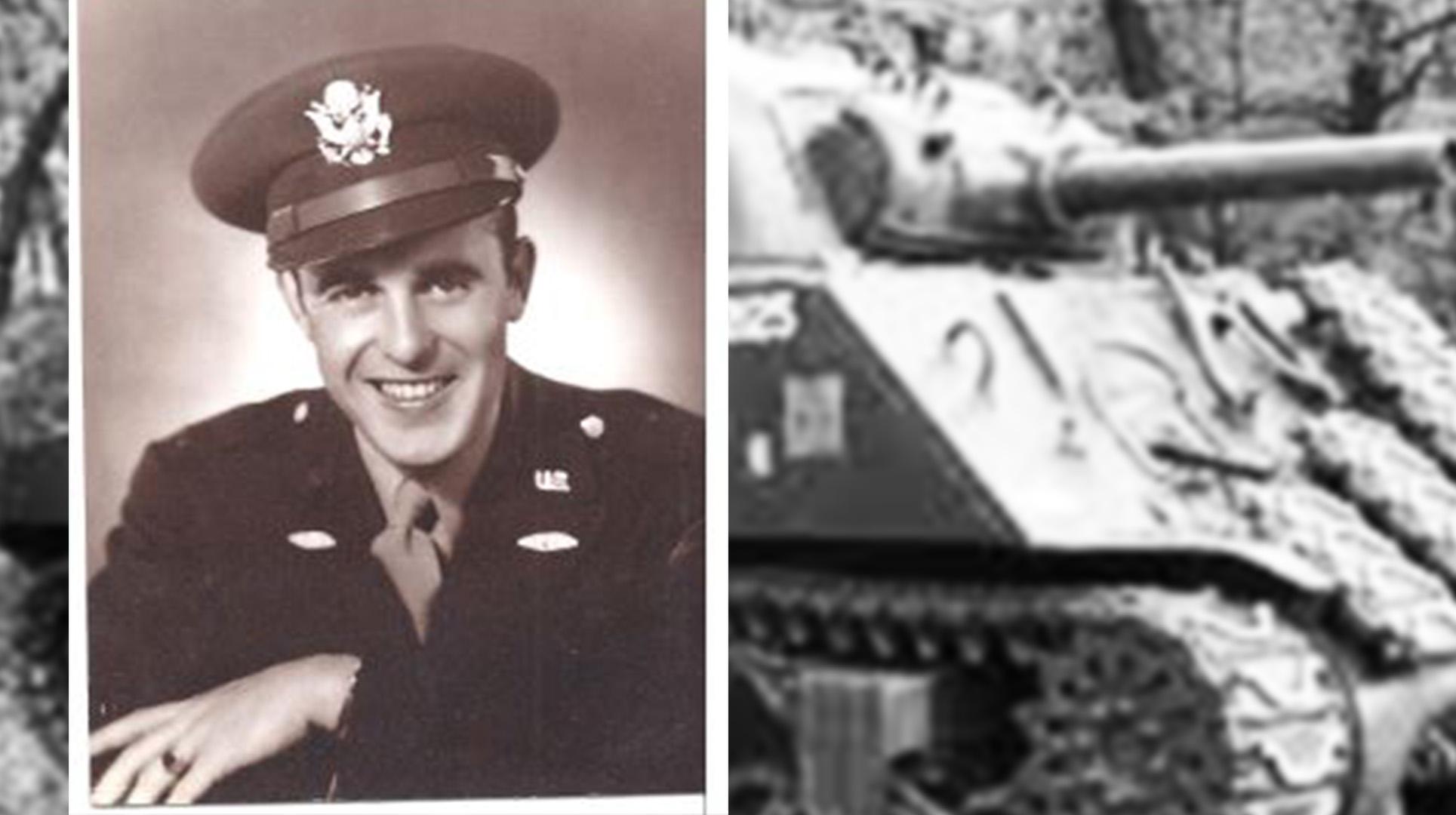

Walker was the commander of an M4 Sherman tank with Company H, 3rd Battalion, 32nd Armored Regiment, 3rd Armored Division. His unit was battling Nazi forces near Hücheln, Germany, when his tank was hit by an 88-mm anti-tank round. Experts believe the round which set the tank on fire, killed him instantly. The survivors of his unit were unable to remove Walker from the tank due to heavy fighting.

At the end of the war in September 1948, the American Graves Registration Command investigated and recovered missing American personnel in Europe including several cases in and around the Hücheln area. Local Germans had been interviewed, but none reported deceased American servicemembers.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news and culture in your inbox daily.

While studying unresolved troop cases in the area, a DPAA historian found that a set of unidentified remains possibly belonged to Walker. However, they weren’t 100% sure if it was Lt. Walker or this other service member, Everette said.

They narrowed it down to two people and requested DNA reference samples from the two sets of families. Next, they got permission to disinter the remains which were sent from Belgium back to the lab at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska. Then a forensic anthropologist analyzed the remains and retrieved DNA samples which were sent to the The Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory in Dover, Delaware.

The identified airman, Staff Sgt. Hall was assigned to the 66th Bombardment Squadron, 44th Bombardment Group. On Jan. 21, 1944, Hall, a left waist gunner on board a B-24D Liberator, was killed when his plane was shot down by German forces near Équennes-Éramecourt, France. His remains were interred in the French cemetery at Poix-de-Picardie.

Army Sgt. Bishop was an artillery soldier with Battery K, 3rd Battalion, 59th Coast Artillery Regiment when he was captured in late 1942 alongside thousands of U.S. and Filipino troops who surrendered to Japanese forces on Corregidor Island. Prisoners endured the 65-mile Bataan Death March and were interred at the Cabanatuan POW camp where more than 2,500 prisoners died. According to the camp and historical records, Bishop died July 28, 1942, and was buried in a camp cemetery.

Along with other unidentified troops from WWII, Walker’s remains were buried in one of the American Battle Monuments Commission sites in the Henri-Chapelle U.S. Military Cemetery in Hombourg, Belgium. The remains presumed to be Walker were disinterred in August 2021 and sent to a DPAA laboratory for analysis.

Scientists used anthropological analysis, circumstantial evidence and mitochondrial DNA to put the pieces together.

“It varies from case to case as to exactly why that person wasn’t able to be identified,” Everette said. Over half of the servicemembers missing from World War II are considered non recoverable because they were lost over water by aircraft or ship losses. Identification can also be impossible when there’s a lack of DNA or physical evidence and incorrect records from the time.

Walker’s remains are at the DPAA’s Nebraska facility and will remain there until he’s flown to San Diego, California where the family wants to bury him in early 2024.

DPAA employs the largest number of forensic anthropologists of any organization in the world, according to Everette. To identify one person, he estimated that it takes the work of between 50 to 100 people with at least some role.

“There’s not an expiration date on how long we’re gonna look,” he said. “We’re gonna look until everybody’s found.”

Collingwood’s daughter, Kirsten, posted the news about her grandfather on social media which was met with comments from friends about how much she and her sister looked like him.

“We’ve always seen the resemblance. It’s funny but since I never saw him in person, I didn’t realize how extreme it was,” she said. “They’re just kind of over the moon over the whole thing to tell you the truth.”

“I walked around kind of like in a dream-like state for a while to tell you the truth,” Collingwood said. “Even today, it’s just sinking in on me. It’s just such a magnificent thing to ever imagine that this could happen.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

- End of an era: The last class of Marine Scout Snipers graduates on Dec. 15

- That one scene: The most unrealistic part of ‘Rambo: First Blood’

- AC-130 destroys truck after watching it launch ballistic missile at US troops in Iraq

- Army veteran launches ‘Hots & Cots,’ a Yelp for enlisted life

- Trench warfare tips: What US troops need to know from Ukraine