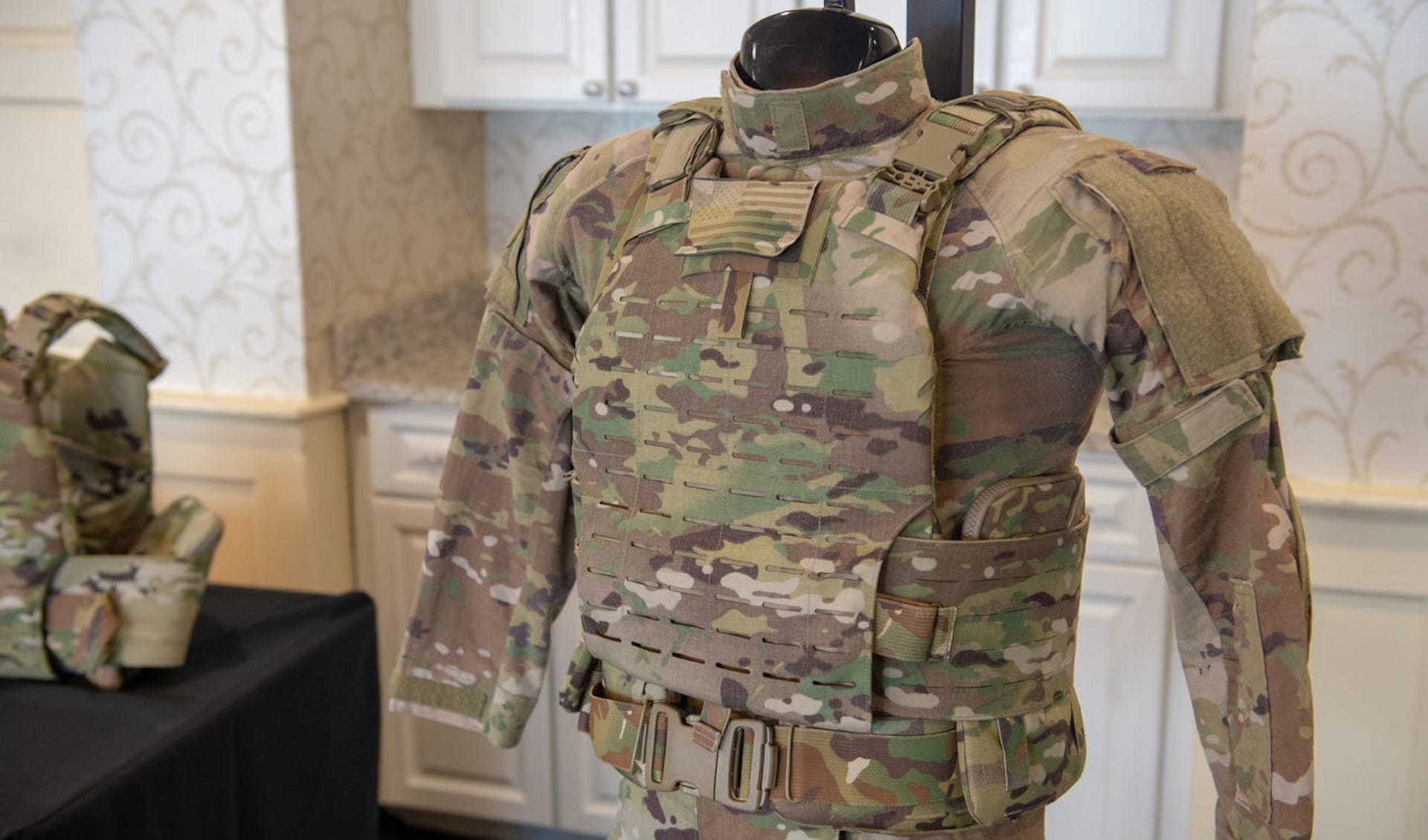

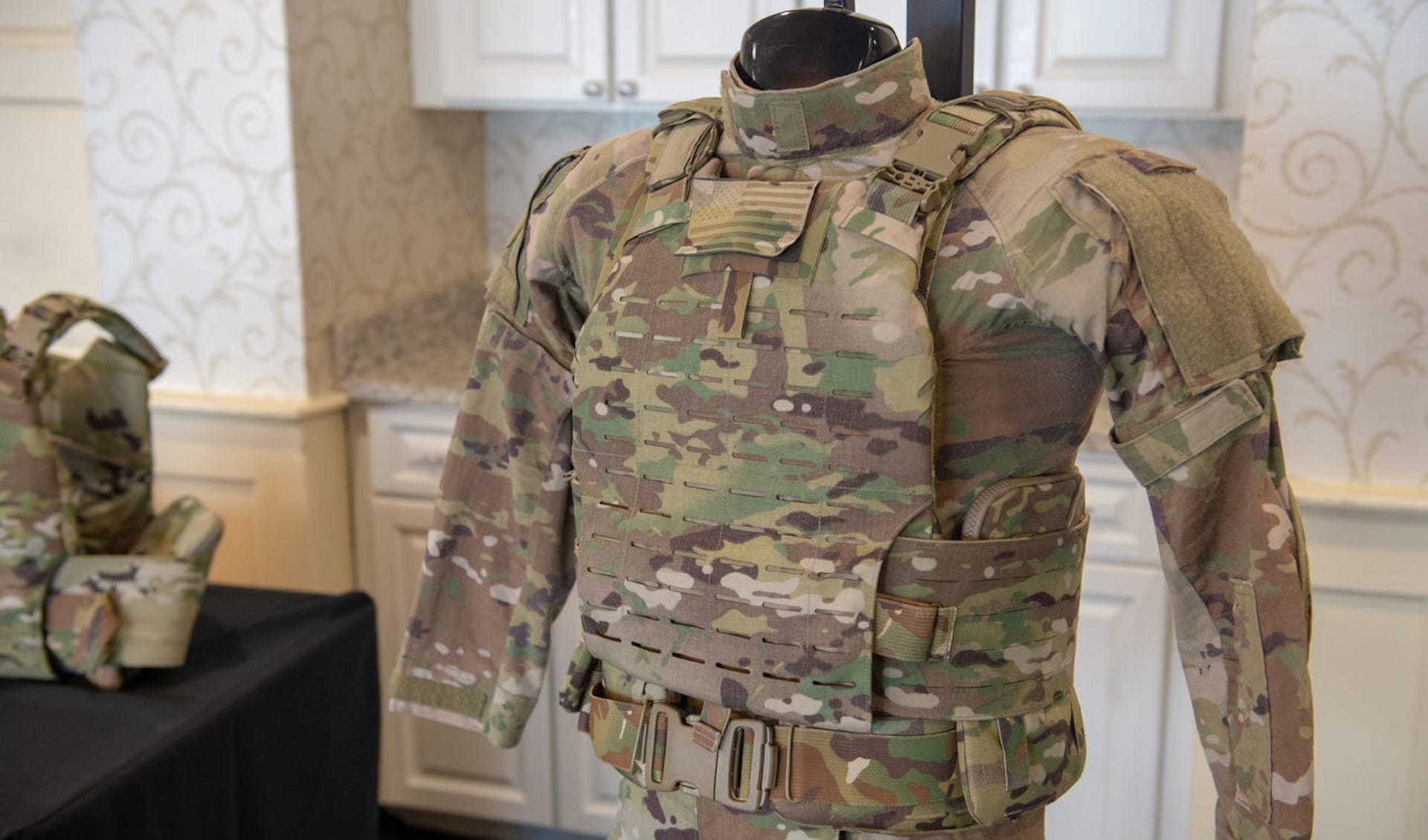

The Army’s new Soldier Protection System has been billed as a lighter and more powerful replacement for the service’s existing personal protective equipment, but a recent evaluation from the Defense Department’s top weapons tester suggests the next-generation system has a long way to go before it can be trusted to reliably protect soldiers downrange.

According to a new analysis from the Pentagon’s operational testing and evaluation arm published in January, the Army spent the 2020 fiscal year testing the lightweight Generation III Vital Torso Protection (VTP) armor plate inserts that, when added into the system’s new Modular Scalable Vest, will offer the first line of protection for soldiers against ballistic threats.

The VTP consists of front and rear hard armor torso plates (either the Enhanced Small Arms Protective Insert (ESAPI) or the X Threat Small Arms Protective Insert (XSAPI)) and corresponding hard armor side plates (either Enhanced Side Ballistic Insert (ESBI) or the X Threat Side Ballistic Insert (XSBI)), per the OT&E report.

Together, the lightweight plates reportedly achieve a 7-14 percent weight reduction over the current armor plates issued to soldiers downrange, according to the Army.

The results of testing, however, were less than encouraging: during initial testing, various versions of three out of four of the armor plates — the ESBI, ESAPI, XSAPI plates, specifically — failed to meet ballistic protection requirements. And while the Army was able to readjust the ESBI and ESAPI plates to meet “revised” requirements, the service is still working to develop a revised version of the XSAPI plate.

Indeed, the OT&E report ends with one simple assessment: “The Army should continue the testing of the lighter-weight Generation III VTP designs,” which roughly translates to “the Army’s next-generation armor plates aren’t ready for prime time.”

And if you’re wondering why that’s such a big deal, we’ll put it this way: The plates may weigh a little less, but don’t count on them to stop incoming rounds — which is their one job.

Now, this isn’t to say that the entire SPS is a loss. Indeed, the system’s new Integrated Head Protective System (IHPS) helped save an armor soldier’s life during an Afghanistan deployment in mid-2019 when the helmet’s next mandible repelled an incoming brick.

But the reliability issues facing the supposed next-generation armor plates — intended to “reduce the burden on soldiers” and be a “game-changer” downrange, according to Army officials — should potentially give any soldier pause before strapping on the new system ahead of a future patrol.

“No plate is delivered to inventory or placed on a Soldier until it passes all testing,” Lt. Col. Stephen Miller, Product Manager for Soldier Protective Equipment, told Task & Purpose in a statement. “No plate will enter inventory until it meets all ballistic and non-ballistic requirements.”

“The DOT&E report accurately describes the standard development process of producing a product, testing a product, and reworking and retesting products that fail until they meet the Army’s requirements,” Miller continued. “The changes made to testing were based on updating testing protocols for the new designs and do not compromise the performance of the plate. Every change to plate design is informed by extensive threat and injury data collected over the last few decades.”

First unveiled in 2016, soldiers are currently receiving certain SPS components through the Army Rapid Fielding Initiative, and the service plans on fielding the complete SPS system to the close combat force in the immediate future.

The Army intends on making a full-rate production decision on the lightweight VTP plate designs upon completion of testing against “additional ballistic threats” in the second quarter of the 2021 fiscal year.

Related: The inside story behind the Pentagon’s ill-fated quest for a real-life ‘Iron Man’ suit