Science fiction fans rejoice: the studio who helped bring a helmeted mercenary and his frog-like companion to life is now helping develop a simulator for Space Force members to learn how to maneuver spacecraft around the Earth.

Does that mean they’ll be flying a TIE Interceptor through enemy blaster fire like in Star Wars: Squadrons? No, not quite, partly because the Space Force does not have any starfighters and proton torpedoes to work with (at least not yet).

But also, space travel is nowhere near as easy as Star Wars makes it look. Complicated astrodynamics means that even simple-sounding maneuvers, like keeping a weather satellite from dipping into Earth’s atmosphere, takes a lot of theoretical know-how to pull off.

“There’s eccentricity, semi-major axis and inclination, the longitude of ascending node, argument of periapsis and true anomaly,” said Melanie Stricklan, co-founder and chief strategy officer of Slingshot Aerospace, Inc., which is leading the development of the simulator. “These orbital elements are not as dimensional as most sci-fi movies make it out to be.”

Those orbital elements sound confusing, but they’re not so bad once you see them in action, Stricklan explained.

“This is especially true once you see how a real spacecraft is launched and operates in orbit, and gain some hands-on practice manipulating the orbital elements in a controlled environment before doing any mission-based planning,” she said.

The problem is, the U.S. military does not have the best tools for teaching astrodynamics — the mechanics of how man-made objects move in space — to service members. Right now the military’s space learning tools are either video lectures or super-detailed mission analysis simulators, and it’s been that way for years.

“Not a lot has changed since we left the Air Force,” said Stricklan, who served in the service’s Space Command along with Charlie McGillis, Slingshot’s vice president for business development.

“They were still using the same software systems that they were when I went through the courses many years ago,” Stricklan said. “So we decided to embark on what success would look like for both students and instructors.”

What they found was that students wanted to learn the basics of astrodynamics in a more hands-on, interactive way. The more students can play around with astrodynamics, the better they understand its effects on spacecraft and execute their missions, Stricklan explained. Unlike their current toolsets, students also wanted a simulator that wouldn’t take 20 minutes to configure, and which they could use at home on their tablets or smartphones.

“The problem is we’ve overcomplicated how to teach basic orbital mechanics and Keplerian laws,” she said. “What we’re going to do is simplify the visualization while keeping the rules physics-accurate so the basics become intuitive and will make a lot more sense than all the terms I threw out earlier.”

Again, orbital mechanics are not as difficult as the daunting terms make it out to be, Stricklan explained, especially when you have the right tools to learn them.

Enter Slingshot Orbital Laboratory, the simulator which Slingshot Aerospace received $1 million from Space Force to develop, along with another $1 million from venture capital. Still, the company wanted the simulator to represent space physics accurately, look good, and feel easy to use, and that’s where The Third Floor, the studio which helped make ‘The Mandalorian’ look so cool, comes in.

“Once I sat down with their CEO, Chris Edwards, I really quickly understood that we shared a creative vision and a passion for making space physics accurate in interactive visual content,” Stricklan said.

The Third Floor has a long history of making space look both great and realistic: their list of credits includes films such as The Martian and Gravity, as well as video games such as Anthem and Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order.

“We are known for visualizing many of the most incredible Hollywood productions, but this seminal U.S. Space Force project gives us an opportunity to make a real-world impact on our country’s national security,” Edwards said in a press release.

The Third Floor used game engine technology to create the Space Force simulator. While the simulator isn’t a video game per se, it has interactive elements that should make it accessible to anyone from the most junior Space Force members to PhD-level experts, explained Albert Cheng, creative director for immersive media at The Third Floor.

“We’re trying to make it much more attuned to students of today who might be playing games, but they don’t necessarily have to,” Cheng said.

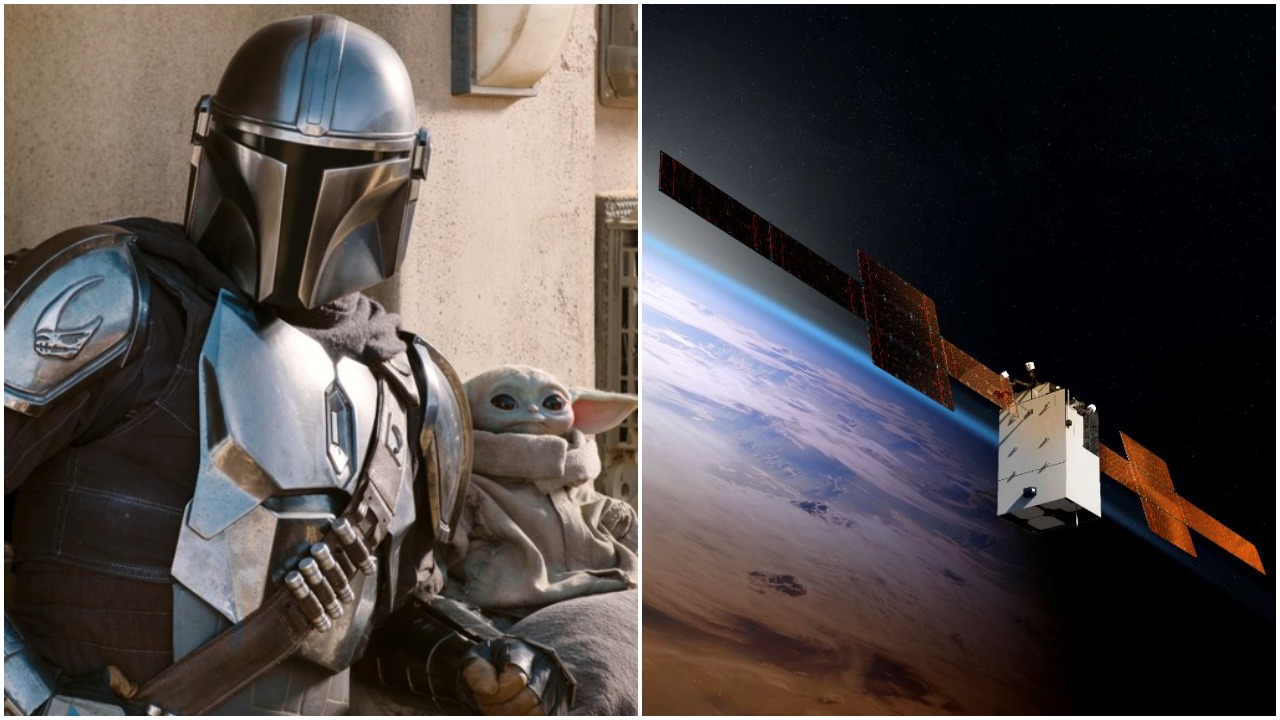

The way the simulator looks now, students can watch virtual objects in space behave in orbit above a beautiful rendering of planet Earth. Surrounding the image is a dashboard that tracks how far the object is above the Earth, how fast it’s moving, where it is in relation to the equator, the shape of its orbit, and other factors. Students will also be able to see how the object moves over time, Cheng said.

“Some of these maneuvers happen over months, if not years,” he explained.

The simulator will start off as an online app for computers, but the plan is to expand it to mobile devices and eventually into augmented reality and virtual reality. Since so many of Space Force’s missions will involve protecting satellites, Cheng said he also hopes to see a mobile app that allows students to raise their devices up to the sky and see satellites on their screen as they pass overhead.

Related: We salute the Army crew that named their tank ‘Baby Yoda’

In the end, the simulator is meant to help prepare space operators for missions. Some of those could include maneuvering satellites out of the way of an approaching debris cloud; coordinating a spacecraft-to-spacecraft rendezvous; getting a communications satellite in place to support other branches of the military or other missions which have not even been invented yet.

“As the Space Force takes on new missions, there will be new tactics and procedures that we’ll learn alongside the Space Force and help bring into the laboratory,” Stricklan said.

It would also be a useful tool for military space operators of all stripes and branches, she explained.

“I do believe the simulator is for anyone in the space operations field,” she said. “But I also think it will prove to be extremely beneficial for leaders of those operators, who may be in staff positions now, to easily go in and refresh their understanding of how these missions work.”

Still, the work of producing the simulator is far from over. Stricklan said the first prototype will be finished in the next few weeks, and the final product will be complete no later than the end of December 2021, though it may be ready before then.

There is no time to lose: there are 2,000 operational satellites in orbit today, but that number is expected to grow to 28,000 satellites within the next three years as the cost of sending satellites into orbit continues to fall, Stricklan said. That’s not even counting the countless dead satellites and pieces of debris in orbit that won’t be coming back down any time soon.

Not only are there a lot of objects up there, but they are also moving incredibly fast. In low earth orbit (1,200 miles or less above the Earth), objects move at 17,000 miles per hour, which means they complete a lap around the planet about every 90 minutes. The speed decreases as altitude increases, but it still makes avoiding orbital debris a tough job.

“You can imagine that understanding the laws that govern spacecraft flight dynamics will be especially important as the probability of collisions increases,” Stricklan said.

The goal is for military space operators to understand space the same way sailors know the seas and airmen know the skies.

“I’m excited for that time when the students that we’re working with can actually govern their own virtual universe,” said Stricklan, who hopes that the simulator “will really allow them to use their hands and gain knowledge on how to manage spacecraft in orbit, so they can truly understand their domain just as deeply as our pilots understand their domain.”