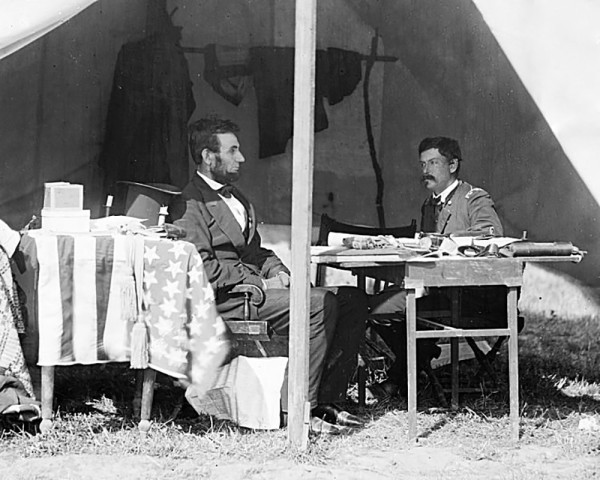

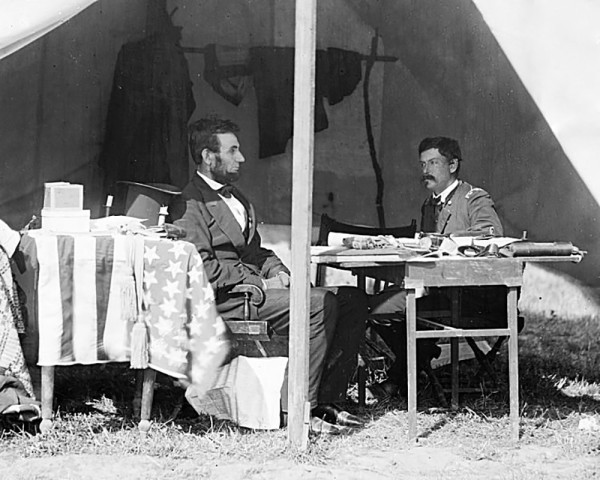

On August 22, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln addressed the Union soldiers of the 166th Ohio Regiment as they passed through Washington, D.C. It was three years into the Civil War and during this time Lincoln had gained a reputation for giving memorable speeches to Union troops.

For those of you who have received a (good) pre-deployment brief from a battalion commander, there’s a recognizable tone. It is one balanced by appreciation for what might be lost in the fight to come, yet tempered by the resolve that the successful completion of your mission is worth the sacrifice. By the war’s conclusion in 1865, it had claimed more than 620,000 lives and left more than a million casualties in its wake.

What stands out about this speech is Lincoln’s capacity for empathy for the everyday soldier. His position as the president never required him to encourage the soldiers who fought for the Union, but he chose to do so. While expressing his gratitude for their service, Lincoln impressed upon the men of the all-volunteer infantry regiment that their role in the war would demand sacrifice and likely take a heavy toll, but that the continued existence of a country where all men had an equal claim to freedom and liberty was worth the cost.

Here’s Lincoln’s speech to the 166th Ohio Regiment in its entirety:

SOLDIERS–I suppose you are going home to see your families and friends. For the service you have done in this great struggle in which we are engaged I present you sincere thanks for myself and the country.

I almost always feel inclined, when I happen to say anything to soldiers, to impress upon them in a few brief remarks the importance of success in this contest. It is not merely for to-day, but for all time to come that we should perpetuate for our children’s children this great and free government, which we have enjoyed all our lives. I beg you to remember this, not merely for my sake, but for yours. I happen temporarily to occupy this big White House. I am a living witness that any one of your children may look to come here as my father’s child has. It is in order that each of you may have through this free government which we have enjoyed, an open field and a fair chance for your industry, enterprise and intelligence; that you may all have equal privileges in the race of life, with all its desirable human aspirations. It is for this the struggle should be maintained, that we may not lose our birthright—not only for one, but for two or three years. The nation is worth fighting for, to secure such an inestimable jewel.