In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Kenneth Howard Norton was a single dad, living in Los Angeles, caring for his son, and struggling to make ends meet. He got up early every morning to run, made breakfast for his son, Ken Norton Jr., then headed off to the Ford plant where he worked, only to punch out of one job, and literally punch into the other. Norton was a fighter, in more ways than one.

Boxing was the way out for Norton, who spent his early 20s chasing his lucky break.

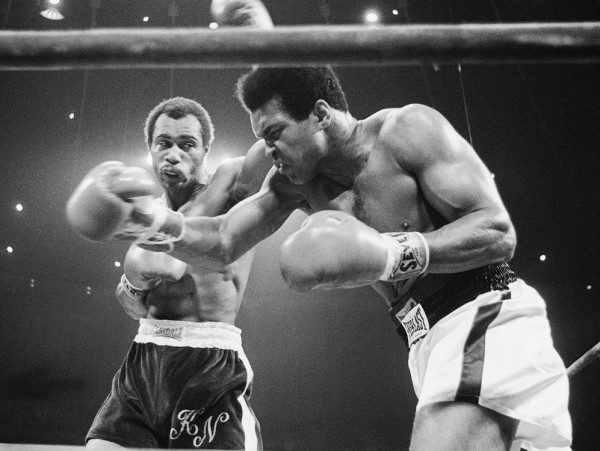

That break came in 1973, when he stepped into the ring against Muhammad Ali, and won, busting Ali’s jaw in the process, and earning the nickname “The Jawbreaker.” At the time, Ali had only been defeated once before, by Joe Frazier in 1971. Norton and Ali would go on to fight two more times, a total of 39 rounds, trading punch for punch, with Norton defeating Ali once, and losing two incredibly close matches.

Norton was a warrior long before then, turning heads with his unorthodox style, and went on to become the world heavyweight champion from 1977 to 1978. But, before all of that, he was a United States Marine.

Norton served in the Marines as a radioman from 1964 to 1967, which is where he began his boxing career. Norton became a renowned fighter while in the Corps, with an amateur record of 24 wins to two losses and went on to fight in, and win, the All-Marine Heavyweight Championship three times.

“In my mind, it was time for me to grow up and become a man. Before I entered the Marines, I was just a boy in a man’s body,” wrote Norton in his autobiography “Going the Distance.”

In his book, Norton credited the Marines with instilling in him a sense of drive and purpose. It was in boot camp that Norton realized that through conviction and discipline even the toughest of challenges could be overcome.

“What they actually were doing was tearing down the old Ken Norton by breaking down those bad habits while building up the new Marine Norton,” he wrote, referring to his first few weeks of boot camp. “You can’t rebuild something on a solid foundation without first tearing down the old. That is what the Marines did with me and it worked.”

When Norton left the Marines in 1967, he was relatively unknown as a boxer, but before that could change, he had to train. The Marines gave him a start as a boxer, but to turn pro, Norton would have to work harder than he ever had before. He found inspiration in his role as a father.

“With a son to take care of, I reminded myself that every time I slacked off in training, I was cheating my son out of a better living,” he wrote in his autobiography. “That motivated me on days that were especially hard.”

Six years after leaving the Marines, Norton had 29 wins and one loss, and it was then that he had his chance to meet Ali in the ring. Norton was a new face and putting him up against Ali, one of the best fighters of the day during his comeback tour, must have seemed a good idea to fight promoters and publicists. The fight was set and Norton was handed $50,000 — his life had suddenly changed. He had money in his pocket and a shot at one of the greatest fighters of the age.

“The first thing I did was make a down payment on a tract house in a better neighborhood for me and my son,” said Norton, in a 1995 interview. “The second thing I did was quit my job at Ford. For the first time in my life, I could just train for a fight, go away for three weeks to a camp. I was a real fighter.”

He met Ali in the ring for the first time on March 31, 1973. The fight was advertised as “Draft Dodger vs. The Former Marine,” a title Norton attributes to Ali, who was renowned as much for his skill as his showmanship and ability to sell a fight. The match took place at the San Diego Sports Arena in Norton’s adopted hometown.

Prior to the event, Ali injured his ankle during training but refused to call off the fight, according to Ali’s former business manager, Gene Kilroy.

“Ali said it’s not going to be that tough,” Kilroy said.

He was wrong.

Norton was physically fit and chiseled, yet critics called the 210 pound, 6 feet, 3 inches tall boxer ungainly, and his style awkward. However, he made it work for him. Norton didn’t follow the typical dance steps of other boxers, especially compared to the agile Ali who relied on speed and quick reflexes to bring down harder-hitting fighters.

Norton was something different. The media — and perhaps even Ali at the time — thought he was just a stepping stone for the famed fighter’s return to the ring, but nobody told Norton. He was an unexpected challenge in more ways than one.

What set Norton apart from his opponents wasn’t just his physique, but his nontraditional style. Where other boxers would strike from the shoulders, Norton would charge head on, but his attack came from below. During their first fight, Norton unloaded on Ali, breaking his jaw. He proceeded to hound Ali for 12 brutal rounds before winning by split decision.

Ali’s own trainer, Angelo Dundee, would later attest to the effectiveness of Norton’s style.

“Kenny had a style that would give Muhammad Ali trouble every day of the week and twice on Sunday. I used to call Kenny the Hopalong Cassidy of boxing due to his unique style and rhythm,” Dundee is quoted in Norton’s autobiography. “He had a style that just put Ali off-kilter and kept him off balance.”

After their match, Kilroy said that Norton visited Ali in the hospital where Ali praised his opponent’s skill, but never wanted to fight him again — which said a lot, considering Ali was never one to balk at a fight.

However, Ali and Norton went on to duke it out once more in September of that year in a match that Norton lost.

On Sept. 26, 1976, the two men met for a third and final time for a fight at Yankee Stadium — unofficially called Ali-Norton III — that would be considered one of the most controversial matches in boxing history.

In an ESPN documentary called “Robbed,” Harold Lederman, one of the three judges of the match, said Norton fought exceptionally well in the first seven rounds, scoring most of the points. At the time, Ali was still the reigning heavyweight champion. The fight went 15 rounds and in the end, the commentators all agreed that Norton won the match. However, the three judges disagreed and scored the bout 8-6, 8-7 and 8-7, all in favor of Ali, who was still the reigning heavyweight champion at the time.

“Ken Norton lost what should have been the classic moment in his career,” said Jerry Izenberg, who was covering the fight for The Newark-Star Ledger.

Throughout their close matches, there was never any animosity — even with the media hype surrounding their conflicting views on military service.

“The media and the public bought it hook, line and sinker, but I wasn’t offended when Muhammad Ali declined to serve in the military; quite the contrary,” wrote Norton in his autobiography. “I respected the fact that he spoke out against the Vietnam War because, after all, that was his right as a citizen of the United States.”

As for Ali, he always respected Norton and his talent in the ring.

“Ken Norton is the best man I’ve ever fought,” Ali said of Norton, after their second match in Inglewood, California, “He is better than Joe Frazier, Jerry Quarry, Sonny Liston—any of them.”

Norton retired from boxing in 1981 with a record of 42 wins, including 33 knockouts, 7 losses and 1 draw. After his boxing career, he made a dramatic change, and went on to act in nine films, and made numerous appearances in others.

Norton suffered a series of strokes later in life and died at age 70, on Sept. 18, 2013.

Decades after his last fight with Ali, Norton is still remembered as the boxer and former Marine who shocked everyone when he broke Muhammad Ali’s jaw and won the match.