Nearly two hours into a Congressional hearing on the military’s role in the June crackdown on protesters in Washington’s Lafayette Square, Rep. Anthony Brown (D-Md.) was focused on something else: Why does the U.S. Army still have 10 bases named after officers who fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War?

“Gen. Milley, I know that you are a student of history,” Brown, a retired Army colonel who had served in Iraq, said on July 9 to Mark A. Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. “Can you comment on the naming of Army installations after Confederate soldiers? Does it reflect the values that we instill in soldiers? Are these Confederate officers held up as role models in today’s military? Does it help or hurt the morale or unit cohesion of service members, particularly that of the Black and Brown service members who live and serve on these installations today?”

Milley, the gruff 62-year-old senior military advisor to the president, looked down at his hands.

“Congressman, we’ve had a lot of discussion in the Department of Defense and the Joint Chiefs on that very topic,” he said, fidgeting with some papers in front of him. “I’ll give you a couple of things to think about.”

Army officials had argued for years against changing the names of its posts, insisting that officers who had fought against the United States during the Civil War had a “significant,” if painful place in its history. Naming an installation in honor of Braxton Bragg, a general and military advisor to the Confederate president, or for John Brown Gordon, a Confederate major general and reputed leader of the Ku Klux Klan, was done “in the spirit of reconciliation, not division,” an Army spokesman said in 2015.

Outside the military, the act of renaming schools, streets, and public buildings named for Confederate leaders — and removing statues of them — has been seen as one way for America to reconcile with its racially-fraught past and present. But the Army has been slower to move in that direction. A senior Army official wrote to a lawmaker in 2017 that doing so would itself be “controversial and divisive” since “the great generals of the Civil War, Union and Confederate, [were] an inextricable part of our military history.”

Milley said none of that.

“I personally think that the original decisions to name those bases after Confederate bases were political decisions back in the 1910s and ‘20s,” Milley said, adding that some were named during World War II. “And they’re going to be political decisions today.”

He recalled a story from his time as a young officer at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. One of his staff sergeants, Milley said, had mentioned that he went to work every day on a base named for a man who sought to keep his grandparents enslaved. And there were many others who likely shared that sentiment: About 20 percent of soldiers in the Army today are Black, Milley noted, and roughly 43 percent of the U.S. military overall are minorities.

“The American Civil War was fought, and it was an act of rebellion. It was an act of treason at the time against the Union. Against the stars and stripes. Against the U.S. Constitution,” Milley said. “And those officers turned their backs on their oath. Now some have a different view of that. Some think it’s heritage. Others think it’s hate.”

The general had conceded that the installation names were a problem. Now he pivoted to his recommendation: A costly, time-consuming study. “I’ve recommended a commission of folks to take a hard look at the bases, the statues, the names, all of this stuff, to see if we can have a rational, mature discussion,” Milley said.

Yet a study, carried out by Army historians, had already taken place when Milley was the Army chief of staff. “Chairman Milley has not yet seen the report but looks forward to reading it,” Col. Dave Butler, Milley’s spokesman, said Wednesday.

In the summer of 2017, the Army Center of Military History began a research effort on how dozens of temporary camps and permanent forts came to bear the names of soldiers who had, in Milley’s words, “turned their back” on the Constitution. The information paper that resulted (“SUBJECT: U.S. Army Posts Named for Former Confederate Officers”) noted, matter-of-factly, that naming decisions were not really a political decision at all.

“With the exception of Ft. Meade in the interwar period, the Army has exercised its discretion in naming posts. As such, it has the authority to rename them,” Jon T. Hoffman, the Center’s chief historian, summarized. “Although many major bases in the south are now named for Confederate officers, there is considerable historic precedent for naming bases after non-Confederates.

“In addition,” Hoffman continued, “There is precedent for re-naming bases, though in most extant cases, the Army decided not to do so.”

But no one outside of the Army was supposed to read that. Though service historians typically publish their research online and in publicly-available books, the information paper regarding posts named for Confederates remained hidden from view since it “reflected badly on the Army,” a source familiar with the matter told Task & Purpose on condition of anonymity.

“They put together this whole report and did nothing with it,” the source said. “That blows my mind.”

Three years after the research was finished — and just days after a 13-page information paper was provided to Task & Purpose in response to a Freedom of Information Act request — the Army curiously decided to publish much of the research online as a “service to the Army and the public,” it said.

“We turned it around fairly quickly” after Army staff requested the research sometime around July 2017, Hoffman said of the research on Tuesday, adding that it was only recently published online “since it was going to be public for a FOIA.”

“We put it on the website in the interest of transparency,” said Charles Bowery, the executive director for the Army’s Center of Military History, mentioning the COVID-19 pandemic and temporary closure of the National Archives had hindered other researchers. “Because this is a topic of public interest at the moment.”

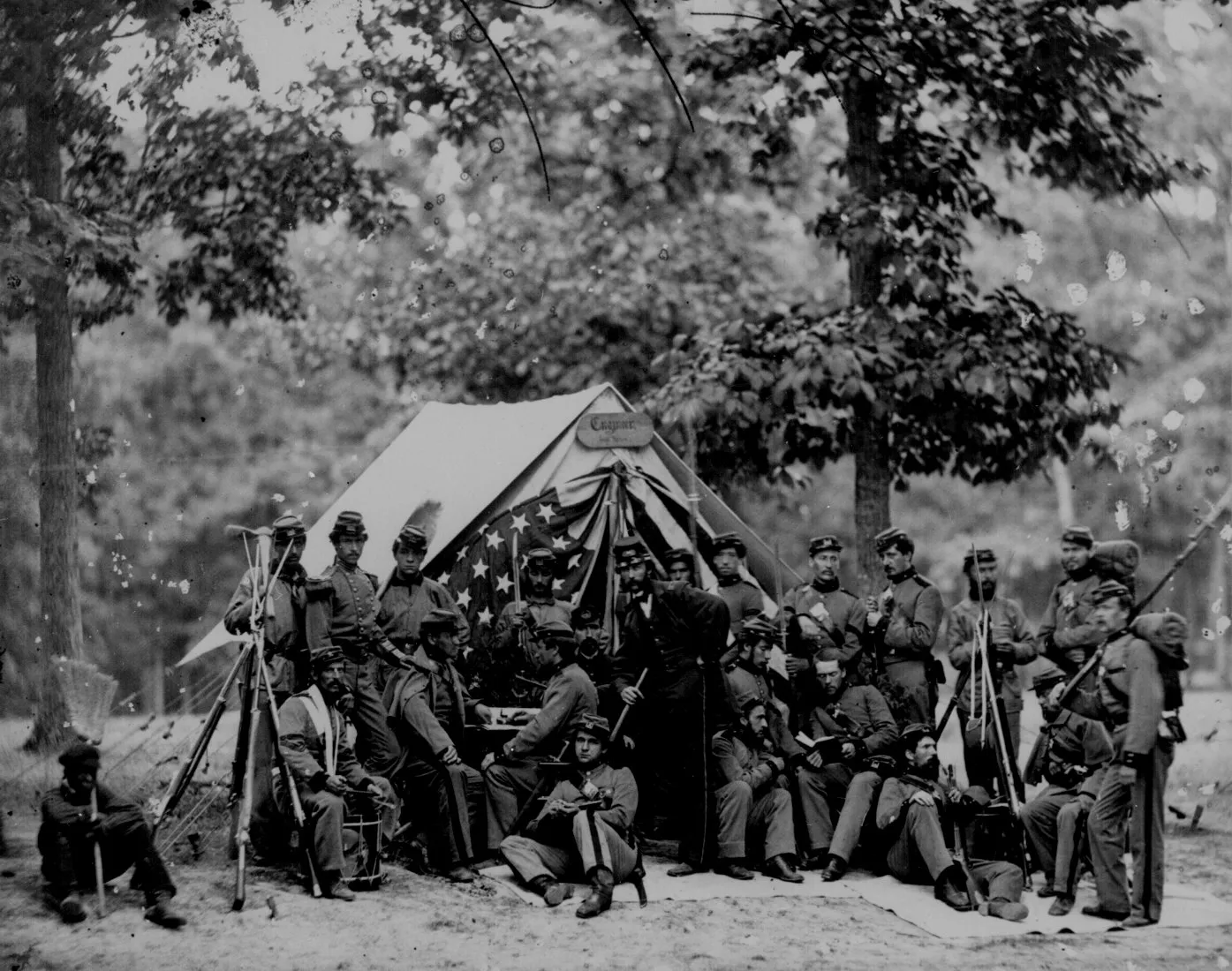

The contemporary debate around base names largely focuses on 10 Army installations in the southern United States, though Army leaders began naming dozens of temporary training camps and permanent forts after Confederates during World War I, according to the 2017 Army research paper.

For much of the Army’s history, local commanders far from Washington were given wide latitude to choose names for their bases. Then, in 1878, the War Department said its regional commanders would oversee base names in an effort to “secure uniformity.” But the Army did not name any posts after Confederates until 1917, an era of American involvement in Europe’s ‘Great War’ that coincided with a resurgence in the Ku Klux Klan, an extremist group that terrorized and murdered Blacks, and the establishment of hundreds of Confederate monuments throughout the South.

In July 1917, about a month after President Woodrow Wilson earned a standing ovation from hundreds of Confederate war veterans as he affectionately recalled how “heroic things were done on both sides” of the bloody conflict, Army Brig. Gen. Joseph Kuhn memorialized an informal policy for naming the many new camps needed to train and equip soldiers before they went overseas to fight in World War I. He offered criteria that chosen names should represent a person from the local area around the base who would “not [be] unpopular in the vicinity of the camp,” while names should focus on “Federal commanders for camps or divisions from northern States and of Confederates for camps of divisions from southern States.”

Kuhn also oversaw the board that provided names to the Army chief of staff, who made the final selection, though some didn’t follow Kuhn’s own policy. “Of the 19 initial camps in southern states, only four were named after Confederate officers,” the research paper said. They were John Brown Gordon; Robert E. Lee, the commander of the Confederate Army; Pierre Beauregard, who started the Civil War with the attack on Fort Sumter; and Joseph Wheeler, a Confederate general who later led U.S. volunteers in the Spanish-American War.

On the initial list was a camp in Alabama to be named for Jeb Stuart, a Confederate major general killed in 1864, though Union Gen. George McClellan was ultimately chosen. And in Greenville, South Carolina, a camp for the Army’s 30th Division was suggested to be named for Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate lieutenant general who oversaw the massacre of hundreds of Union prisoners during the war and later became a leader in the Ku Klux Klan, its first “grand wizard.”

“Lt. Gen. N.B. Forrest, C.S.A. Born in Tennessee. Served at Shiloh, Chickamauga and Murfreesboro. Died at Memphis,” the list stated of Forrest’s accomplishments, ignoring the brutal war crime that inspired Black Union soldiers to shout “Remember Fort Pillow” as a rallying cry, and Forrest’s post-war service leading a group that would terrorize Black families in the South. Though the Army ultimately decided to name the camp after Col. John Sevier, who fought in the Revolutionary War, a separate training camp in Tennessee bore Forrest’s name throughout World War II.

“Curiously,” the Army paper noted, Maj. Gen. Tasker M. Bliss, then acting chief of staff, claimed that both the Union and Confederates on the list had, wrote Bliss, “contributed during their lives to the development of the United States and the acquisition by American citizenship of its present status,” including Robert E. Lee.

Yet even Lee, though he is lionized in the South today, favored moving on from the Confederacy’s legacy. “I believe if there, I could not add anything material to the information existing on the subject,” Lee wrote in an 1869 letter declining an invitation to mark Confederate memorials in Lexington, Va., about a 12-day foot march from the U.S. Army base now bearing his name. “I think it wiser, moreover, not to keep open the sores of war but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife, to commit to oblivion the feelings engendered.”

It was more than 50 years after the Civil War had ended and the first posts named for Confederates were in place. “Their selection of names does not indicate that racism played a major role or that there was a concerted effort to bolster southern pride in the Confederacy,” the paper says, noting a segregated military was the favored policy at the time.

Then, in August 1918, the Army named a new camp in Fayetteville, North Carolina for Braxton Bragg, a Confederate general and native of the state, citing his service during the Battle of Buena Vista in the Mexican War. Another camp followed in October named for Henry Benning in Columbus, Georgia. The paper noted lobbying efforts by the United Daughters of the Confederacy for the Confederate brigadier general widely known as a “vocal advocate” for secession.

“After the first batch of post names were announced, Southern newspapers commented favorably on the adoption of Confederate names,” the 2017 Army research paper says, including a front-page headline from The Richmond Times-Dispatch noting the “American War Department” had “officially paid tribute to the military genius of noted Confederate war chiefs.”

The Army established dozens of additional posts during World War II, and camps in the South were “generally named after southerners,” the research paper notes, “though not all were connected with the Confederacy.” Just as today, the Army was mindful of its public image: “When it reestablished Camp Jackson in South Carolina, a memorandum emphasized that it was named after the president and hero of the War of 1812, not Confederate General Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson,” the research paper says. “At the same time, the Historical Section considered it ‘inadvisable’ to name a Georgia camp after General Benjamin Lincoln of the Revolutionary War ‘because of its connotation to the people in that section of the country.’”

In Dec. 1940, the Army named a base in Louisiana after Leonidas Polk, a Confederate lieutenant general and friend of Jefferson Davis, and designated Camp Barkley in Abilene, Texas in honor of a private awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism during World War I. Then in April 1941, Maj. Walter Bedell Smith (who would become a general and much later, head the CIA), dismissed suggested names from the Revolutionary War and World War I for a Virginia camp in favor of A.P. Hill, a Confederate lieutenant general faulted by some historians as stumbling into the battle at Gettysburg.

“One newspaper noted that ‘by memorializing the great … hero of the Army of Northern Virginia,’” the research paper said, “‘The War Department shrewdly took the measure of local responsibilities’” and the “‘Army appealed to a vein of patriotism no self-respecting Virginian could be without.’” The newspaper noted the local community saw “no controversy” in the decision.

Two senators, including future president Harry Truman, requested the Army name a new camp in Missouri “after the Confederate officer who led the Missouri brigade in the Civil War.” Instead, the Army named Fort Leonard Wood in Nov. 1940 after Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood, a New Hampshire-born officer awarded the Medal of Honor in 1898. An officer in the Army’s Historical Section opined: “Civil War heroes have already been generously honored. Attention should be directed to the World War.”

But other groups in the South got their wish. The Army in June 1941 picked Confederate Lt. Gen. John B. Gordon for the namesake of Camp Gordon, Georgia, prompting a telegraph to the War Department from the Sons of Confederate Veterans: “Thank you for your thoughtful and gracious act.” (Gordon, the long-rumored head of the Georgia Ku Klux Klan, was denounced by 44 of his direct descendants in June.)

By 1942, thousands of American troops were training at a new camp in Oregon named for a West Point graduate killed in battle with Mexico and another in Texas named for a Medal of Honor recipient. But thousands more were moving through bases in the South bearing the names of Confederates before shuffling off to fight the Nazis in Europe.

As the research paper notes, Fort Pickett in Virginia, for Confederate Maj. Gen. George Pickett, was picked over two suggested non-Confederate names, although community input “did not affect the decision.” Yet other post names in the South proved controversial because the Army decided against a Confederate name.

Despite “the repeated strong urging of a congressman” and lobbying from the United Daughters of the Confederacy for a Confederate officer, the Army in early 1942 named Fort Campbell on the Kentucky-Tennessee border for William Campbell, a Tennessee-born politician and soldier who served briefly as a brigadier general for the Union.

“No doubt in an effort to intimidate, the congressman even demanded to know the identity of the individual responsible for the decision,” the research paper notes.

Two other bases in the South were highlighted by the research paper: Fort Stewart in southeast Georgia earned its name at the “urging of a local congressman” in Oct. 1940 in honor of Brig. Gen. Daniel Stewart of the Revolutionary War and Indian campaigns, and Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, named in August 1941 for Maj. Gen. Adna Chaffee Jr., the “father of the armored force” who had died that same month.

Anthony Brown, a young Black Army officer later elected to Congress, first entered a U.S. Army base in Alabama in 1984 to learn how to fly helicopters about 40 years after it was named for Edmund Rucker, a “relatively unknown” Confederate officer, according to the Army’s history. Rucker beat out a heroic lieutenant from World War I, since another fort in Massachusetts shared his name and “could lead to confusion.”

Army officials first considered naming a post for Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood in Dec. 1940 before opening what would become Fort Hood in Killeen, Texas in the fall of 1942. Though some this year called for renaming the base in favor of Master Sgt. Roy Benavidez, a Medal of Honor recipient who saved a trapped eight-man patrol in Vietnam, senior Army leaders during World War II rejected other soldiers noted for their heroics, including Maj. Gen Robert Howze and Capt. James Fannin, who was killed during the Texas War for Independence in 1836.

“There is no record of the decision process,” the research paper notes. But the name stuck, despite pleas in August 1944 to change the name in honor of Lt. Gen. Lesley McNair after he was killed in France. “The effort continued into 1945, with Gen. Joseph Stillwell adding his voice to the campaign,” the research paper says. Among the reasons for denial: “undesirable popular and political repercussions in the State of Texas.”

Perhaps the most controversial decision over the name of a base was overseen by some of the Army’s most-revered generals.

In 1940 the Army took over and expanded a National Guard base in Tennessee named for Austin Peay, a former state governor. But the name had to be changed since it would house and train federal troops, according to Gen. George Marshall, the Army chief of staff, who urged that “the desires of the State authorities will be followed unless it is found that the name selected is unsuitable for psychological or other reasons.”

The state’s choice was Nathan Bedford Forrest, a man of “notorious reputation” for his Civil War exploits and leadership of the Klan in its early years, according to the research paper. In his endorsement, the Tennessee adjutant general noted that Forrest was a native of Tennessee who was born near the Tullahoma camp.

A retired general went further in his support of ‘Fort’ Forrest: “The [most] outstanding fighting man (except Andrew Jackson) ever produced was Nathan Bedford Forrest,” retired Maj. Gen. Lyle Brown wrote to Army leaders in Nov. 1940. “The naming of a military station for him would be approved by every well informed person in this part of the United States.”

By Jan. 1941, the Army brass was satisfied with the pick: “The G-3 division believes that the name Camp Forrest is appropriate.” Army staff members Col. Harry Twaddle, who later rose to major general, and Lt. Col. Omar Bradley, later a five-star general of the Army and first chairman of the Joint Chiefs, signed the order announcing the change.

The base, closed in 1946, was one of the Army’s largest training bases during the war.

It’s difficult to know how race played in the decision-making of the Army’s senior leaders, though the research paper highlights the institutional racism of the day that is impossible to ignore.

“The Army as an institution, along with most of the nation at that time, favored a policy of segregation and limited opportunities for blacks,” the paper says of the World War I naming period. “The Army specifically segregated blacks in separate units with white senior officers and some black junior officers.”

And of World War II, the paper notes that “among the many officers involved more directly” with the naming decisions, very few were from the South, “though geographic origin would not have been dispositive of racial attitudes, and it would be difficult in most of these cases to determine their actual views on race.”

Still, the paper mentions Gen. McNair, from Minnesota, who “pushed back strenuously against a proposal during World War II to end segregation in the Army in order to simplify manpower and training issues,” the paper says. “He preferred to accept that inefficiency in order to maintain segregation.” (Fort McNair in Washington, which hosts the Army’s Center of Military History, is named for the general.)

Yet President Truman, a one-time advocate for a Confederate base name, outlawed segregation across the military in 1948, though “the order [was] largely ignored by the services for months,” according to a 2008 Defense Department timeline on military integration, which noted “widespread” support for segregation in the Army in 1951.

This past July, the House and Republican-led Senate passed a $740 billion defense spending bill with a provision stripping Confederate names from all Army bases — over a veto threat from President Donald Trump, though even many Republicans dismissed the president as increasingly fighting a lone battle, including Sens. Mike Rounds (R-S.D.) and Marco Rubio (R-Fla.).

Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy stated that he was “open” to the changes in June, and Milley, Trump’s senior military advisor, wasn’t defending base names in Congress. The Marine Corps had in April led the way banning what its top officer called “symbols ” with “power to inflame feelings of division” — Confederate flags — and Defense Secretary Mark Esper signaled that he wasn’t likely to honor Confederate history from the Pentagon podium.

“I hope the president will reconsider vetoing the entire defense bill, which includes pay raises for our troops, over a provision in there that could lead to changing the names,” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) told Fox News after Trump’s veto threat.

“If the president says none of that’s important, what’s important … is keeping the names of Confederate generals on military bases, and so he vetoes all the good to accomplish that, I predict that he will have his veto overridden,” Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) said Sep. 18. A final compromise bill has been delayed until after the Nov. 3 elections.

Milley had been wrong in that July hearing. The Army had mostly exercised “its discretion” in naming posts, as its top historian had summarized, mentioning nothing of politics.

But the general was right on how they would be changed.