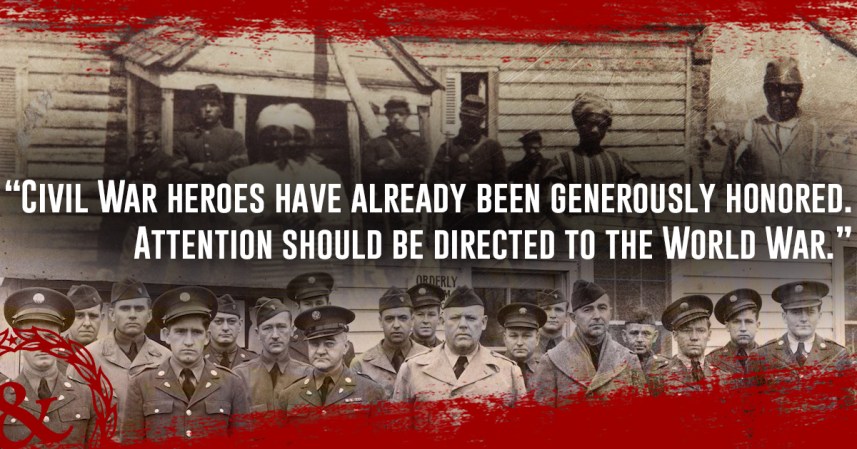

The Confederate officers for whom 10 Army bases are named betrayed their country by taking part in an armed rebellion against the United States, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff told lawmakers on Thursday.

“The American Civil War … was an act of treason at the time against the Union, against the Stars and Stripes, against the U.S. Constitution – and those officers turned their backs on their oath,” Army Gen. Mark Milley told the House Armed Services Committee.

Milley’s comments are the strongest indication to date that top military leaders would like to consider renaming those bases.

In remarks on bases named after Confederate generals, Joint Chiefs Chair Gen. Mark Milley says, "The Confederacy, the American Civil War…was an act of treason at the time against the Union, against the Stars and Stripes, against the U.S. Constitution." https://t.co/mD5HJulzUt pic.twitter.com/BGcbUO98ce

— ABC News (@ABC) July 9, 2020

President Donald Trump, however, has repeatedly said he will not let that happen.

“The United States of America trained and deployed our HEROES on these Hallowed Grounds, and won two World Wars,” Trump tweeted on June 10. “Therefore, my Administration will not even consider the renaming of these Magnificent and Fabled Military Installations.”

Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy had been open to the idea of renaming the bases before the president made his position on the matter known.

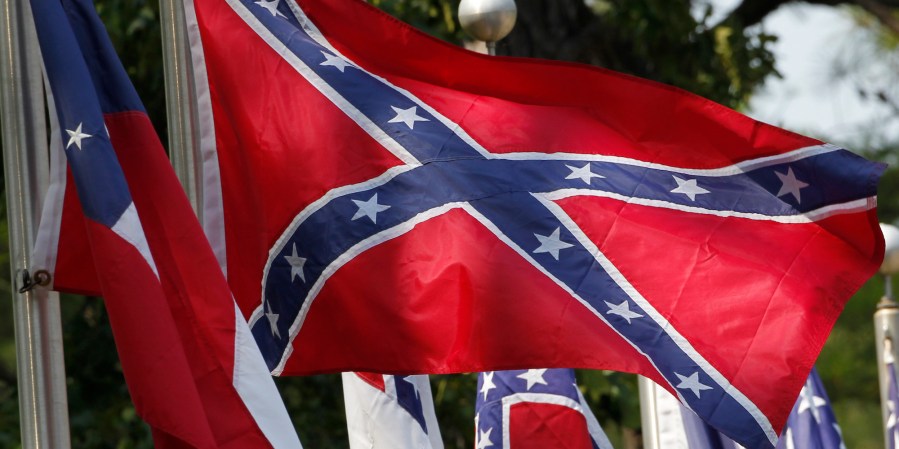

Separately, Marine Corps Commandant Gen. David Berger announced in February that the Confederate flags and other Confederate symbols would be banned from Corps installations.

The Navy made a similar move in June by banning Confederate paraphernalia from work areas and public spaces.

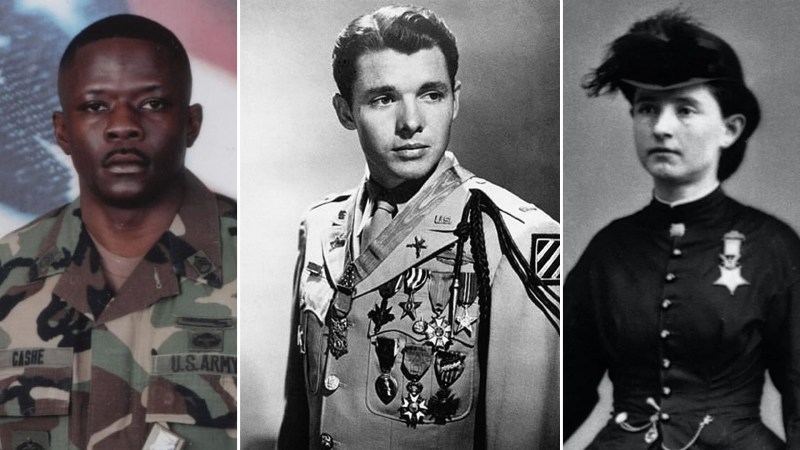

On Thursday, Rep. Anthony Brown (D-Md.) asked Milley if having Army bases named for Confederate officers helps or hurts morale and unit cohesion within the military.

Milley acknowledged that the joint chiefs have held several discussions on this matter. Overall, minorities comprise 43 percent of the U.S. military. Black soldiers make up more than 20 percent of the Army as a whole and 30 percent of certain individual units.

“For those young soldiers that go on to a base – a Fort Hood or a Fort Bragg or a fort whatever named after a Confederate general – they can be reminded that that general fought for an institution of slavery that may have enslaved one of their ancestors,” Milley said.

“I had a staff sergeant when I was a young officer who actually told me that when I was at Fort Bragg,” he continued. “He said he went to work every day on a base that represented a guy who enslaved his grandparents.”

Since the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers, the Defense Department and military branches have launched a number of efforts that are meant to eliminate racial disparities in how service members are promoted and disciplined.

Milley said he has also recommended that a commission look into the bases named for Confederates and related issues.

“We’ve also got to take a hard look at the symbology, the symbols: things like the Confederate flag and bases and statues and all that kind of stuff,” MIlley. “The way we should do it matters as much as that we should do it.”