In the summer of 1969, hundreds of thousands of people descended on a small dairy farm in Bethel, New York for a watershed moment in recent music history: The Woodstock Music and Art Fair.

The four-day festival was a celebration of peace, youth, life, love, long hair and incredible music. However, the fiestival might have ended in disaster, were it not for an unexpected ally.

This is the inside story of how the U.S. Army ran a resupply mission to party-goers at Woodstock.

It was August 1969, and Clark Stahl was enjoying temporary duty at West Point in New York. It’s what the former Army helicopter pilot referred to as “pretty sweet gig” in a phone interview with Task & Purpose.

Recently returned home from the Vietnam War, Stahl was a 23-year-old warrant officer who’d flown medevac missions during his tour downrange. Now he was enjoying a stint as the lead pilot flying West Point cadets around in a Huey; part of their familiarization training ahead of graduation.

Clark Stahl, left, with his father inside a CH-47 in the early ’70s.Photo courtesy of Clark Stahl

“Our duties there weren’t exactly strenuous, shall we say,” Stahl said. “We’d fly a couple of hours a day and then spend the rest of the time by the swimming pool.” So when Stahl’s commanding officer approached him to ask if he and his guys would be available that Friday, Aug. 15, and into the weekend, his answer was “yeah, sure we can do that.”

The reason they were needed? To provide medical aid and resupply for a rock festival. More specifically: Woodstock.

“We kind of looked at each other and said ‘what the hell is a rock festival?'” Stahl recalled with a laugh. “Of course we knew nothing about Woodstock. It was explained to us that there’d be a lot of big names and they didn’t know how many people would end up showing up, but they expected it’d be quite a few more than they originally thought.”

There were. More than 400,000 people arrived at the event — more than double the number anticipated. The roads, what few there were to begin with, became bogged down with mud and stuck cars. The influx of people coupled with a lack of access, made food and medical care a concern, as Task & Purpose noted in August 2017.

When one of the vendor’s booths was burned down overnight — one of the few instances of violence at Woodstock — due to anger over inflated prices and a shortage of food, a plan was already in motion.

As the festival kicked into high gear, Stahl and his crew were instructed to ferry in supplies. (Though Stahl said he recalls seeing a number of other helicopters arriving at Woodstock over the course of the festival, as far as he can remember, his was the only military aircraft.)

One thing that hasn’t faded from memory is the sight as he flew overhead that first time.

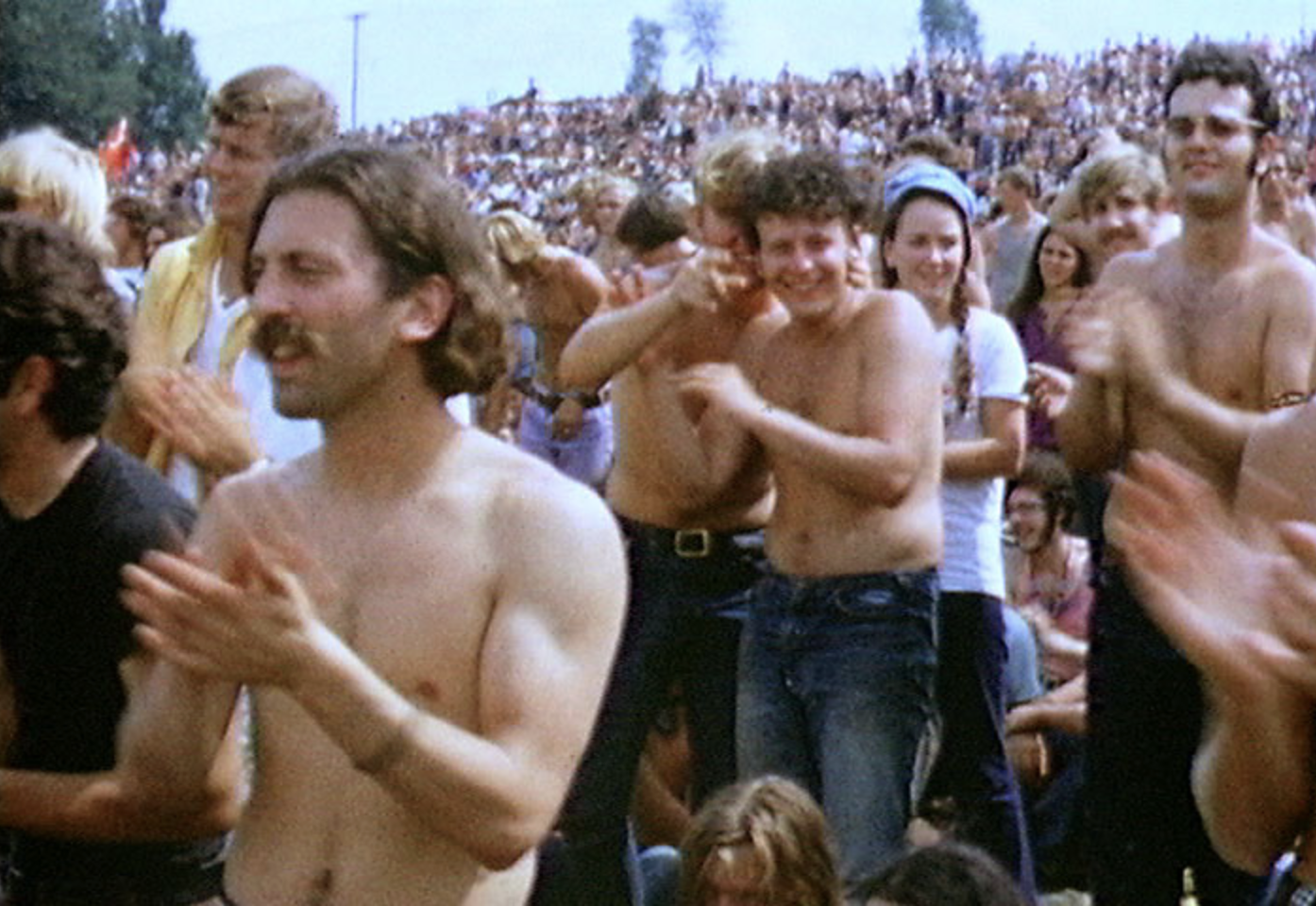

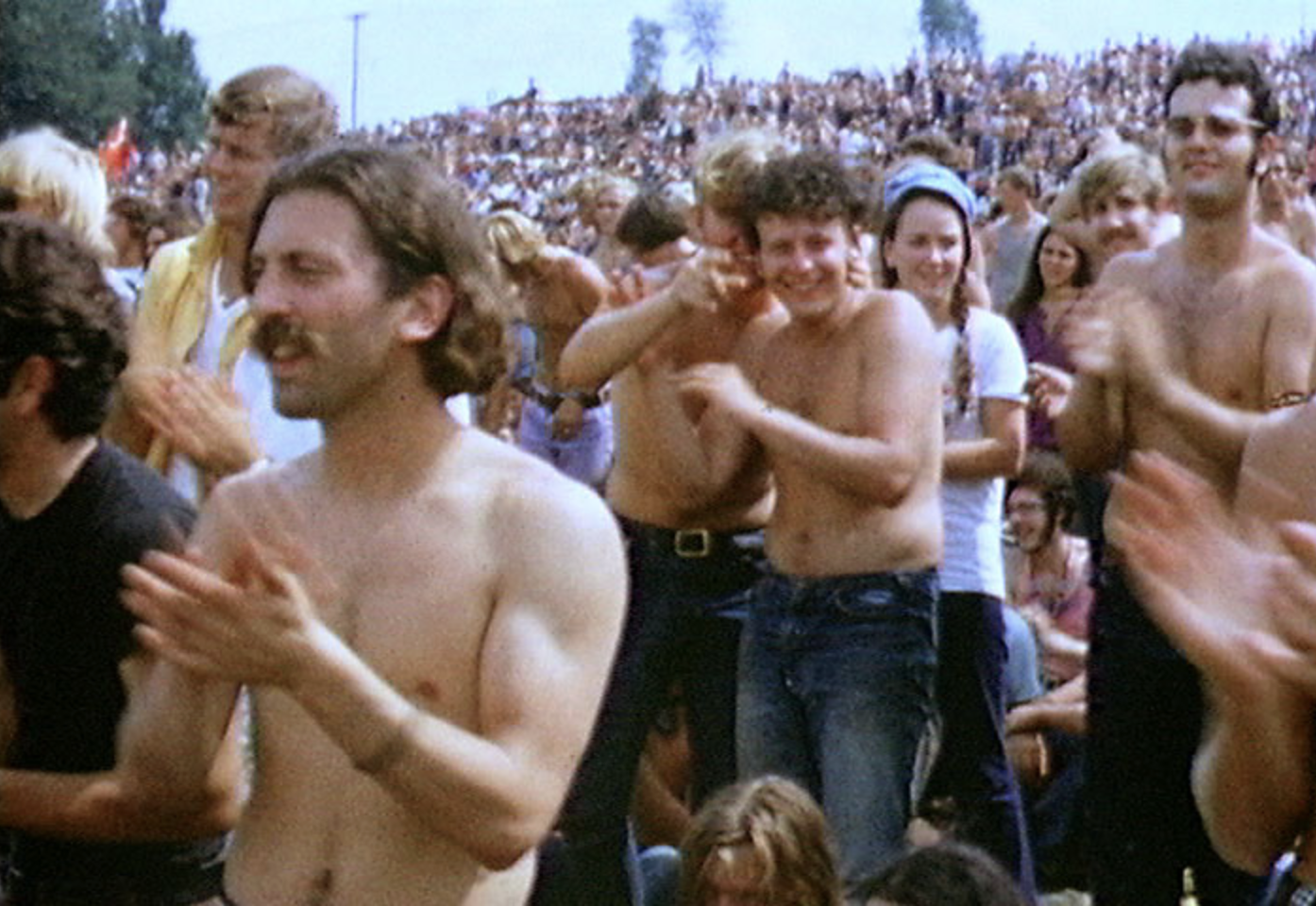

Woodstock, August 1969.

upload.wikimedia.org

“I can remember quite vividly, it’s probably one of two times in my flying career, which spanned 50 years altogether, where we flew over something and were completely speechless,” Stahl, who left active duty in 1971 and served in the reserves until he retired in 1991, told Task & Purpose.

“Seeing this mass of humanity there, it’s hard to register,” he continued. “There’s nothing to compare it to or judge it by. Not knowing what to expect, that’s probably the one thing that sticks in my mind more than anything else.”

As the helo made its approach Stahl and his copilot made a number of slow and lazy circles over the venue.

“It was to make sure the people there realized that this isn’t Uncle Sam or the man coming in to affect any kind of law enforcement or anything like that,” Stahl said. “That we’re just here to help.”

Though Woodstock didn’t frame itself as an anti-war event, the festival took place during the height of the Vietnam War, and with the counterculture music scene closely aligned with the anti-war movement, the sight of an incoming Army helicopter likely conjured up images of American militarization to those on the ground. That concern was captured by John Morris, the production coordinator for the festival, who was onstage when Stahl’s helicopter came in:

“It was like a wave,” Morris said in Woodstock: The Oral History. “You could see people start to look up … and all I said was, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, the United States Army’ — and you could feel it and you could hear it, the tension — ‘Medical Corps.’ And the crowd broke into a cheer that was just fantastic. And just about then you could see the red crosses on the side.”

Circling above, Stahl still remembers that moment.

“You could almost see the reaction of the crowd, going from kind of surprised and wary, to more relaxed and accepting,” he said. “It sounds funny to say that, but you could almost see it happen.”

Once he got the go ahead, Stahl touched down in a small clearing that was roped off for the helicopter. On the first flight in they offloaded medical personnel and supplies, but after that the details get a little hazy, Stahl said.

“I read a couple of accounts that said we had supposedly delivered sandwiches and I thought about it, and I suppose we could have,” Stahl told Task & Purpose, adding that he and his crew conducted anywhere between six to a dozen sorties over the course of the concert, though he couldn’t recall the exact number.

“They would put people or stuff on board and we would take it out there and drop it off without knowing exactly what it was, without really caring. It was all part of the effort to keep things safe and peaceful,” he added. “We knew they needed to get stuff in and out of there, but the main focus was on the health and safety aspect of it, and making sure nobody had any injuries or medical issues, and if they did, they’d have the ability to treat them.”

Though Stahl was back in the states and no longer cruising over the jungles of Vietnam, in a way the mission was oddly familiar.

“I flew medevacs in Vietnam, so I was used to the concept of medical evacuation and help from the sky, if you will. So my mindset was that this was just kind of a continuation of what I’d done in South East Asia, and helping those in need on the ground.”

Decades later, and with a lengthy career in the Army behind him, Stahl said that if he hadn’t been drafted in 1967, it’s likely he would have been there just the same, only on the ground instead of the air.

“Oh yeah. Had I not been in the Army and been anywhere close by, it’s very likely I would have been there, you know? Sex, drugs, rock and roll and that stuff, of course!”