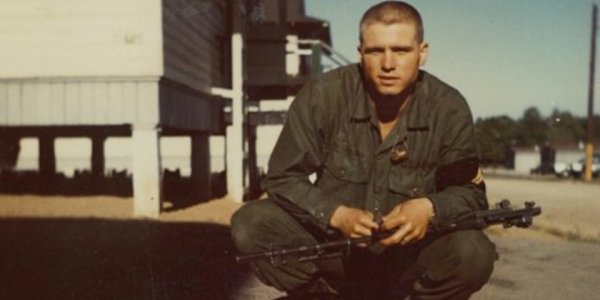

When James C. McCloughan graduated from college in 1968, he knew exactly what he wanted to do with his life: teach. But first he had to take a little detour. Shortly after accepting a job at a high school in his hometown in Michigan, he got a draft notice in the mail. The next spring, he was in South Vietnam, working as a combat medic assigned to the 21st Infantry Regiment.

Now, nearly 50 years later, President Donald Trump will award McCloughan, 71, the Medal of Honor he earned for actions in the course of a bloody, two-day battle that nearly cost him his life.

Of the 89 American soldiers choppered in to the outskirts of Don Que to stop a North Vietnamese advance in May 1969, only 32 emerged unscathed. 12 were killed, many were wounded, some went missing in action. McCloughan himself would return home to South Haven, Michigan to begin a career as a high school teacher and coach with two Purple Hearts, two Bronze Stars, and a body full of shrapnel.

But his work during that engagement, the Battle of Nui Yon Hill, was nothing short of extraordinary: He was credited with saving the lives of 10 men.

It was McCloughan’s old platoon leader, Randy Clark, who spearheaded the effort to see the guy he once called “Doc” awarded the nation’s highest award for combat valor. But McCloughan has made it clear that, as far as he is concerned, the medal wasn’t earned alone.

“This is not a James McCloughan award, it’s an award for my men, for Charlie Company,” McCloughan told the Detroit Free Press last year as Congress mulled a Pentagon recommendation to waive the time limit for high military decorations, paving the way for him to receive the Medal of Honor. “We had a horrendous battle, a situation you will never forget…I wasn’t going to leave my men, and they were going to protect me.”

On May 13, 1969, a day after their landing zone was attacked by an enemy sapper, leaving four American soldiers dead and 24 wounded, Charlie Company was ordered to conduct a helicopter assault on Nui Yon Hill. McCloughan had seen his fair share of combat by that point. In fact, the lifesaver had killed a North Vietnamese Army soldier the first day he arrived at the LZ, and the fighting was constant from there.

But this mission was specially dire. McCloughan recalled in an interview with the Army that Charlie Company was down to 89 men, and they had no idea how many NVA soldiers occupied Nui Yon Hill. They would soon find out the answer: a lot. In fact, the incoming fire was so heavy as the helicopters approached the objective that they couldn’t land, and instead had to hover 10 feet or more off the ground. The soldiers literally jumped into action. Many were injured. McCloughan was not, although his pack weighed 135 pounds. Two helicopters were shot down.

What followed was a two-day slog so full of close calls and death and bleeding, shocked men needing to be dragged off the battlefield that, at one point, McCloughan made a pact with God.

“I bargained with him that if he allowed me to live,” he told the Army, “I’d become the best coach and teacher and dad that I could be, and I also promised that I’d hug my dad and tell him I love him.” McCloughan added that, for his generation — at least, in his Midwestern upbringing — it was unusual for a man to show affection like that to his father. But war was changing him.

The Army would later determine that Charlie Company, with close air support, had managed to fend off an attack from three sides by an estimated 1,500 NVA and 700 Viet Cong. The battle had reduced McCloughan’s company to 32 men. One of those killed, Pfc. Daniel J. Shea — the company’s last remaining medic besides McCloughan — died on Nui Yon Hill and would be posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor within months of the battle.

Sleep-deprived, severely dehydrated, and wounded, McCloughan passed out at the end of the battle. He hadn’t consumed food or water for two days. He had been shot in the arm and struck twice by RPGs. 10 men were alive because of him.

But McCloughan stuck to his promise. As he told the Army, the first thing he did when he arrived at the airport in Chicago on March 6, 1970 — after many more firefights and close calls and friends killed in action — was embrace his father and tell him he loved him. Then he picked up where he left off, taking the job at South Haven High School that he had accepted before his draft notice arrived. For the next 40 years he taught psychology, sociology, and geography. He also coached.

In addition to his Purple Hearts, Bronze Stars, and, now, the Medal of Honor, McCloughan’s resume includes being inducted into the Michigan High School Coaches Association Hall of Fame, the Michigan High School Football Coaches Association Hall of Fame, the Michigan High School Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame, the Olivet College Athletic Hall of Fame, the Bangor High School Hall of Fame, and the South Haven High School Hall of Fame.

WATCH NEXT: