Contamination from former or current military installations has ignited a nationwide review of water on or around bases that used a firefighting foam containing toxic chemicals.

The military is now testing nearly 400 bases and has confirmed water contamination at or near more than three dozen, according to an analysis of data by the Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News. The new numbers offer the best look to date at the potential scope of the problem.

But despite more than $150 million spent on the effort so far, the process has been slow and seemingly disjointed. The Air Force, for example, has completed sampling at nearly all of its targeted bases; the Navy, barely 10 percent. The Army has not begun. The branches and the Pentagon say they are coordinating, but have varying responses on how many bases must be tested, and limited information about remediation timelines and cost.

“We’re going to be dealing with this for quite some time.”

The lack of answers has been so confounding that Sen. Bob Casey, D-Pa., moved to amend the defense spending bill to compel the Pentagon to release a list of all bases that used the foam.

But with so many sites to evaluate, the cleanup “is not super-simple to do,” said Mark Correll, an Air Force official.

While this process plays out, the chemicals in soil or groundwater could continue to leach into drinking water, experts say, meaning the problem could grow.

“I am not going to be terribly surprised if, once a month for the next several years or something, we hear of a small community somewhere that was impacted,” said Christopher Higgins, a top researcher on this type of contamination and a professor at the Colorado School of Mines. “We’re going to be dealing with this for quite some time.”

Used in manufacturing and in military firefighting foam, PFCs have been linked to health problems including testicular and kidney cancers, thyroid disease, and high cholesterol.

For residents near former naval bases in Willow Grove and Warminster, Pa., the issue surfaced three years ago, when they learned their water had been tainted by PFOA and PFOS, perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) that are unregulated and little understood.

Used in manufacturing and in military firefighting foam, they have been linked to health problems including testicular and kidney cancers, thyroid disease, and high cholesterol. Research on other potential health effects is ongoing, and some experts contend that even water below the EPA’s health advisory level is unsafe.

Contamination has been found near 27 military bases in 16 states, according to the Air Force, Navy, and Army. The military has also addressed contamination in on-base drinking systems on 15 installations.

The contamination is also cropping up near airports, private plants, and fire stations. Attention has focused on the military because of extreme cases near bases where about 60,000 residents were affected.

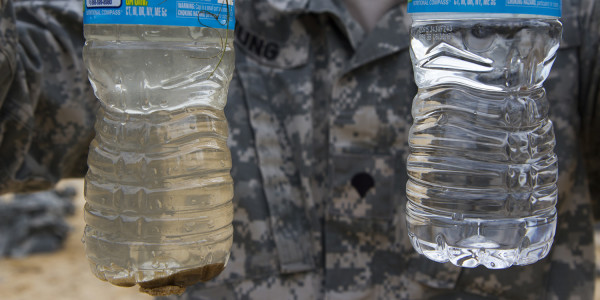

Staff Sgt. Shane Pentheny, 22nd Civil Engineer Squadron Water and Fuels System Maintenance technician, performs water-quality tests on water taken from several base buildings March 9, 2017, at McConnell Air Force Base, Kan. WFSM tests chlorine, fluoride and pH levels daily to ensure the base populace receives quality water.U.S. Air Force/Airman 1st Class Erin McClellan

In Newburgh, N.Y., where drinking water was tainted by the foam used at an Air National Guard base, officials are pressing the military to pay for connecting city residents to a new clean water source.

“The Department of Defense, I think, is coming around to the reality that they have a significant problem on their hands nationwide,” said Basil Seggos, commissioner of the state Department of Environmental Conservation in New York.

The Air Force, Navy and Army say they have similar plans: First, they will sample bases where the foam, known as aqueous film-forming foam, may have been used, then assess whether remediation is needed. After that, the cleanup would begin.

“The overriding issue is preventing migration (of the chemicals) into the wells,” said Karnig Ohannessian, the Navy’s deputy assistant secretary for environment. “That’s going to take a longer time.” But, he said, “we’re starting to have our arms around this.”

Officials say they have addressed sites with the greatest danger of drinking-water contamination. They have also checked on-base drinking water and are providing clean water where needed. The rest of the process is slow, they say, because they must follow complex federal rules.

“Priority one is make sure that there is no exposure to the contaminant. Once we’ve assured that… you’re talking eight years to get yourself to a remediation solution.”

Whether the chemicals — which don’t degrade in groundwater — move quickly or slowly depends on what type of water system they’re in, said William Battaglin, a research hydrologist for the U.S. Geological Survey. “Waiting (to clean up) doesn’t necessarily make it tremendously worse, but there could be situations where waiting would make the contaminant move from the source,” he said.

The Air Force, which has the most affected bases, began incorporating PFCs into existing cleanups around 2013. Officials then started paying more attention to the chemicals as the EPA began focusing on them, said Correll, deputy assistant secretary of the Air Force for the environment, safety, and infrastructure. As of March, he said, 196 of 207 bases had been sampled, the first step. The inspections should end by 2021.

“Priority one is make sure that there is no exposure to the contaminant,” Correll said.

“Once we’ve assured that … you’re talking eight years to get yourself to a remediation solution.”

Navy officials established a policy for the testing and cleanup last June, a month after the EPA released new guidelines, and have completed sampling at 11 of 127 bases. Ohannessian could not offer a schedule, saying only that the process will be “pretty long-term.”

“We don’t really have a priority one, two, three to just run through the 127 sites,” said Richard Mach, director of environmental compliance and restoration policy at the Navy.

He said it was “hard to say” what bases would be tested next because officials did not want to alarm residents before notification or sampling began.

The Army will follow the same process as the Navy and Air Force, a spokesman said, but inspections at 61 bases have not yet begun. Only one non-military drinking well, in Ayer, Mass., has been found with contamination above the EPA’s advisory level, a spokesman said.

———

©2017 The Philadelphia Inquirer. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.