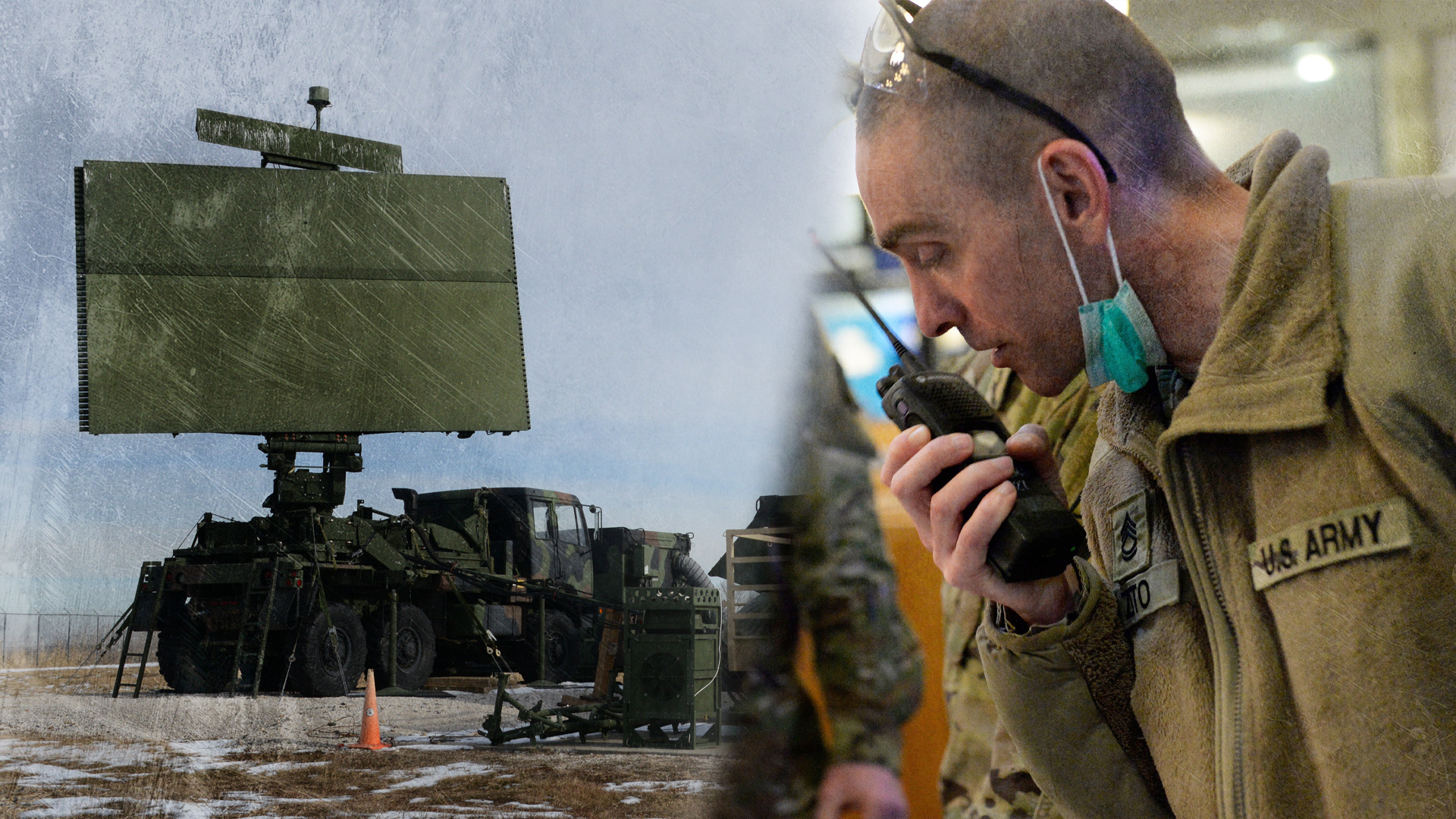

Russia’s use of electronic warfare in eastern Ukraine provides a preview to U.S. troops about what it will be like to fight an adversary that can intercept and jam their communications, sever all links to their drones flying overhead, and blind their radars and other sensors.

“Electronic warfare is almost by definition one of the hardest things to discern on the battlefield,” Russian military analyst Michael Kofman told Task & Purpose. “It seems early on Russia was not well prepared to employ these capabilities, but now there are numerous stories of localized jamming and disabling of drones.”

Open source analysts such as Oryx Blog suggest the Ukrainians have destroyed several Russian jammers and deception systems, including the Krasukha mobile electronic warfare system, which is meant to jam drones and other weapons systems guided by radar, said Kofman, director of the Russia Studies Program at CNA, a federally funded research and development center.

However, the Russians have still been able to jam Ukraine’s military communications as well as the Global Positioning Receivers on the drones that the Ukrainians use as artillery spotters, the Associated Press recently reported.

“They are jamming everything their systems can reach,” an unnamed official with a civilian organization that provides the Ukrainian military with intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance told the Associated Press. “We can’t say they dominate, but they hinder us greatly.”

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest in military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

The ongoing battle in Eastern Ukraine shows that electronic warfare does not distinguish between inside and outside of the wire. Russia’s tactics in Ukraine may indicate that the days when U.S. troops could comfortably sit in a tactical operations center with perfect communications are coming to an end.

Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran would likely try to jam and intercept U.S. troops’ communications and block or deceive navigation systems in a war, said Lt. Col. Tyson Wetzel, senior Air Force fellow with the Atlantic Council think tank in Washington, D.C.

“U.S. forces need to be prepared for their links to unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and drones to be targeted, as we have seen happen in Syria for years.” Wetzel told Task & Purpose. “Russia, and other potential adversaries, will target communications to and from UAVs and drones, their navigation systems, and their intelligence collection systems. U.S. forces have to be able to operate in a denied or degraded electronic environment, with a focus on fielding secure and resilient links to all UAVs and drones.”

Under an electronic attack, American service members may need to resort to seemingly anachronistic forms of communications. For example, the Ukrainians use analog landline field phones because they cannot be jammed by the Russians, Coffee or Die reporter Nolan Peterson revealed.

A contested electronic environment could also make it more difficult for U.S. military aircraft to strike their targets. In 2018, Army Gen. Tony Thomas, who led U.S. Special Operations Command, said during a speech that an AC-130 gunship over Syria had been temporarily disabled by an electronic warfare attack.

Thomas told Task & Purpose on Monday that the AC-130 was still able to carry out its mission despite the electronic jamming. It is unclear whether the electronic attack was launched by Syria, Russia, or the Islamic State group.

“But we had to work around in a ‘dirty’ battlefield as opposed to some of the areas in which we had been operating in previous years,” Thomas said, referring to the contested electromagnetic environment. “It also reminded us that our peer adversaries have that capability in large quantities.”

The threat of electronic warfare remains “an ever-present reality” for U.S. troops in Syria, said Air Force Lt. Col. Gina McKeen, a spokeswoman for Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve.

“U.S. troops and coalition partners are working together to minimize the electronic warfare threat to operations in the Levant in order to ensure the enduring defeat of Daesh [ISIS],” McKeen told Task & Purpose.

In October 2020, the Defense Department released its “Electromagnetic Spectrum Superiority Strategy,” which calls for investing in “revolutionary, leap-ahead technologies” to combat electronic warfare.

“Recognizing U.S. reliance on the EMS [electromagnetic spectrum], our adversaries have spent 30 years studying, investing, and implementing policies, capabilities, and procedures with the single focus of gaining military advantage over U.S. forces,” the strategy says. “These adversaries are developing and fielding advanced technology that targets U.S. capabilities across the EMS.”

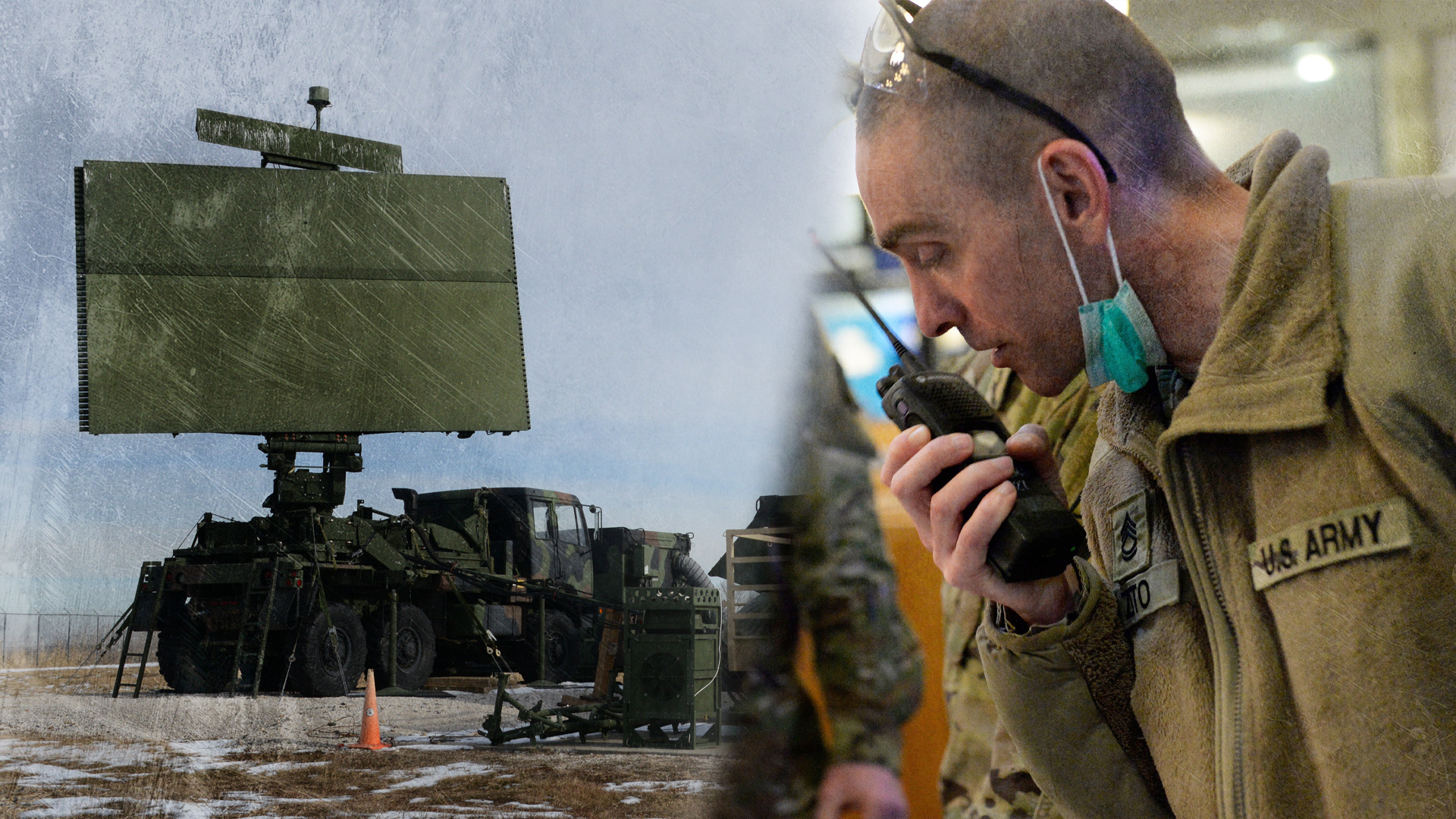

For junior enlisted U.S. service members and noncommissioned officers, Russia’s use of electronic warfare in Ukraine is a reminder that they have an electronic signature – just as they have heat and visual signatures – that can be detected, targeted, and hit, said retired Army Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, former commander of U.S. Army Europe.

“We should expect that the Russians will jam/intercept our communications,” Hodges told Task & Purpose. “They already do this occasionally. That’s why it’s important we train on this at our training centers and home station so that soldiers are disciplined to minimize Russian EW [electronic warfare] effects.”

U.S. troops must also continue to practice proper procedures to make sure that they are always clear and concise whenever they communicate in a contested electronic warfare environment, he said.

“Assume that you can be jammed and/or intercepted and thus targeted, no matter what system you are using,” Hodges said.

The Russians have learned that lesson the hard way by using cell phones when their communications systems failed. That has made it easy for the Ukainians to find, target, and strike Russian troops, including general officers.

Right now, the Russians have effectively put their jammers on blast so that regions of Eastern Ukraine are electromagnetic dead zones, where neither the Ukrainians nor Russians have access to communications, radars, and other sensors, said retired Air Force Lt. Col. Glenn “Powder” Carlson, president of the Association of Old Crows, a professional organization for electronic and cyber warfare professionals.

Carlson compared the situation to a scene in the movie “The Hunt for Red October,” in which a Navy officer describes how the Soviet fleet was moving too quickly to detect anything on active sonar: “They could run over my daughter’s stereo and not hear it.”

If U.S. troops had to fight in such an environment, they would likely need to use High, Very High, and Ultra High Frequency radios to communicate with each other, Carlson told Task & Purpose.

“EW [electronic warfare] is very much a chess match,” Carlson said. “There’s always moves and counter moves. When I came into it, it was called ‘electronic countermeasures.’ And then you had electronic counter-countermeasures. From those terms, we’ve changed to ‘electronic support,’ ‘electronic attack,’ ‘electronic protect,’ because otherwise we end up with too many ‘counters’ in there.”

The Russians have long been known for their prowess in electronic warfare. Philip Karber, a Marine veteran and national security analyst, has made 39 trips to Ukraine since March 2014, spending a total of 189 days with Ukrainian combat troops. He remembers one incident years ago when the Ukrainians he was with not only came under Russian artillery fire, but the Russians also called the Ukrainian commander on his cell phone to taunt him.

However, even though Russia’s latest invasion of Ukraine began in late February, it has only been recently that Russian electronic warfare efforts have become increasingly effective, said Karber, president of the Potomac Foundation, a think tank in Washington, D.C.

That is partially because the Russian forces that took part in the initial assault on Kyiv may not have been properly trained how to use electronic warfare systems, Karber told Task & Purpose. Those forces may have also been too dispersed and moving too quickly to launch effective electronic warfare attacks. And it is possible that the Russians found they were inadvertently jamming their own systems.

One lesson of the war in Ukraine is that American troops are vulnerable to electronic warfare attacks, said Karber, who argued the U.S. military is too narrowly focused on countering cyber threats.

“We have not addressed the vulnerability – particularly of our command posts – that are dependent on communication, which has grown exponentially,” Karber said. “We have not gotten used to operating without electronic communication, either using land wires or runners, which both the Russians and Ukrainians have learned to adapt to as well. We are really not prepared for that level of electronic warfare, in my opinion.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Someone apparently leaked classified Chinese tank schematics to win an online argument

- Flip-flop-wearing Air Force commandos saved 2 lives on the way back from training

- How Ukraine is using artillery to stop Russian forces in their tracks

- The Navy might have a garage sale for the Littoral Combat Ships they just built but don’t want

- Ukrainian fighter calls US soldier for help fixing Javelin missile launcher

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.