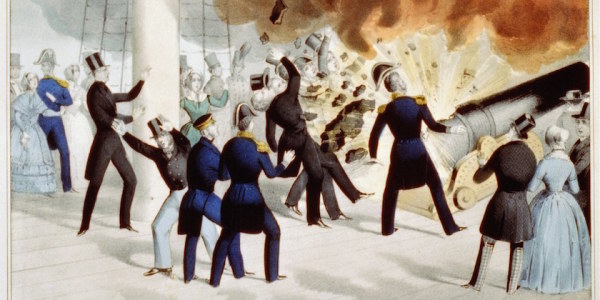

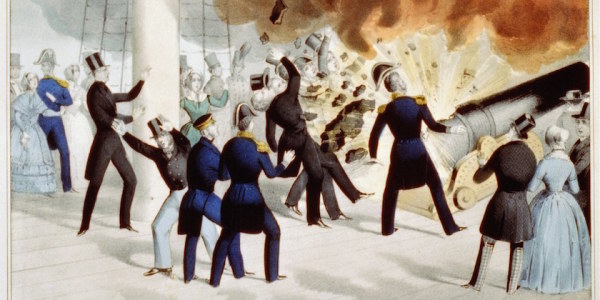

Hundreds of Washington’s most famous citizens began the morning of Feb. 28, 1844, with a lavish pleasure cruise that ended gruesomely, in a horrific tableau of blood-splattered gowns, severed heads, limbs and molten metal. The disaster that was the USS Princeton’s debut came about as ambition and fame converged to kill Secretary of State Abel Upshur and decapitate Secretary of the Navy Thomas Gilmer — and somehow won the president a new bride.

Commodore William Montgomery Crane was one of the great war heroes of the War of 1812. His family served famously in the American Revolution, and his brother, Col. Ichabod Crane, is believed to be the namesake of the main character in Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” William Crane fought pirates during the First Barbary war, and won honors for gallantry at Tripoli. In recognition of his many accomplishments, he was given a cushy job as chief of the new Bureau of Ordnance and Hydrography. Things were going well for Crane until he met Commodore Robert F. Stockton — the man who would lead him down the path to severing the secretary of the Navy’s head.

Stockton was a charismatic young man from a famous, wealthy family. He served during the War of 1812 and later negotiated a treaty founding of the state of Liberia as a colony for former slaves returning to Africa by leveling a pistol at the King’s head. Next he found his fortune in California gold mining and speculation — Stockton, California, is named after him. President John Tyler offered him the post of secretary of the Navy, but he preferred to return to uniformed service.

Stockton pushed forward to advance an audacious plan to develop the most technologically advanced, well-armed ship the American Navy had ever built. He reported to Crane, but as a favorite of the President he was given significant leeway, which rankled Crane. Stockton enticed John Ericsson, inventor of the screw propeller, to leave his native Sweden to work on the project. When the Navy ran out of funding, Stockton funded the rest out of his family wealth.

The ship was christened the USS Princeton after the Revolutionary War battle and Stockton was given command. Not coincidentally Princeton, New Jersey, was the birthplace of Stockton and the location of his alma mater. Princeton was a state-of-the-art death machine. She could travel faster than any other steamship thanks to a propeller and a set of sails. She was meant to be as deadly as she was fast, armed with two 12-inch, 225-pound wrought iron guns called the Peacemaker and the Oregon.

Related: 117 Years Later, The Sinking Of The USS Maine Remains A Mystery »

Stockton had a flair for showmanship. He arranged for nearly 400 of Washington’s social elite cruise down the Potomac. President Tyler invited his sweetheart, Julia Gardiner, who had recently turned down his marriage proposal, accompanied by her father. Cabinet secretaries, congressmen, and even former First Lady Dolley Madison turned out. Stockton, resplendent in dress uniform, welcomed guests with the Marine Corps Band. Ericsson was noticeably absent. The relationship had soured, and rumors circulated it was because Ericson felt it unwise to fire the untested Peacemaker.

It was a clear morning, quite warm for February. The gunners rammed 40 pounds of powder down the Peacemaker. The guests cried with awe as the great gun threw a 228-pound ball over two miles. They retired below decks for a decadent lunch of roasted fowl, ham and fine wines. During one toast, the president found he was out of champagne and remarked in jest that the “dead bodies” must be cleared out. Stockton cheerfully responded that “There are plenty of living bodies to replace the dead,” as he handed the president a full bottle.

As the luncheon ended, guests murmured that they wished to see the Peacemaker fired once more in honor of George Washington. Stockton took the request as an order from the secretary of the Navy and took most of the group above decks. One guest began to sing a patriotic ditty, and Tyler stayed below to listen. At the moment the lyrics came to a line about Washington, the great gun exploded.

What was once a display of military might had become an engine of horror. Fire and molten metal flew in all directions. As the cloud of smoke smothering the decks cleared, those who had survived the blast were surrounded by dead bodies, severed arms and legs, and deep red blood flowing across the deck. Some were struck deaf, their eardrums destroyed by the blast. Julia Gardiner’s father was found separated from his arms and legs. The secretary of the Navy’s head was severed by a shard of metal. An arm belonging to the charge d’affaires for Belgium flew across the ship and struck a lady in the head, knocking off her bonnet. All told, six men were killed and 20 more were injured, including Stockton, who miraculously survived but suffered burns to his arms and face.

“My God,” he exclaimed. “Oh, that I were dead, too.”

The living were left to the grievous task of telling those below decks. The president told his sweetheart that her father was dead. She fainted into his arms. Dolley Madison could “never afterwards trust herself to speak of that terrible afternoon, and never heard it mentioned without turning pale and shuddering.”

In the investigation, Crane, Stockton, and Ericsson were exonerated. The commission found that the Peacemaker’s forgers had incorrectly adapted a British hooping technique.

Stockton went on to serve in the Mexican-American War and later as a senator. Ericsson designed the ironclad USS Monitor. President Tyler fared well, as the dramatic event cemented affections with Julia. They were married four months later, in a scandalous near-elopment. Even the Princeton was able to be repaired and served at home and in the Mediterranean until 1849.

Crane, however, never recovered. Though his career had not suffered, he felt responsible. On March 18, 1844, he closed the door to his office at the Navy Department, pulled out a knife, and slit his own throat. His lifeless body was found a day later, adding one more casualty to the death toll caused by the USS Princeton. Naval Surface Warfare Crane Division and the USS Crane were both named after him, in effect, the last memorials to one of the great tragedies in early American naval history.