In May 1999, then-Lt. Col. David Goldfein’s F-16CJ fighter jet was rocked by the explosion of a surface-to-air missile during a mission during the Kosovo War. Ejecting from his aircraft, the future Air Force Chief of Staff landed in a ravine and evaded Serbian fighters until he was rescued by a combat search and rescue team, according to the Washington Post; he was just one of two pilots shot downed as part of Operation Allied Force during the short conflict.

More than two decades after Goldfein’s harrowing ordeal, the Air Force is exploring a more elegant option for future combat rescue missions: an unmanned system that, air-dropped onto the battlefield, is capable of whisking downed pilots and other wounded service members out of dangerous territory, Aviation Week reports.

Call it Uber for medevac — just without the surge prices.

In a request for proposal posted to the U.S. military’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) website on May 2, the Air Force Research Laboratory detailed requirements for a a ‘Personnel Recovery/Transport Vehicle’ that’s “capable of transporting 2-4 military personnel (one in medical litter) with no onboard traditional pilot … for supporting combat search and rescue, personnel recovery, and special operations in the field.”

The ideal platform will operate within a 100 mile radius and at a top speed of 100 knots, conducting truncated takeoffs and landings in “unprepared locations” of between 50 and 150 feet wide. In addition, the platform should be capable of hauling up to four military personnel with a 1,400-pound equipment load and enjoy “the capability of operating in all theaters of operation to include desert, jungle, mountainous, and maritime (ship to shore transport),” per the SBIR solicitation — and do so with a relatively low acoustic signature to avoid detection.

“Diverse environments will require operations from new isolated locations, at greater distances, requiring low cost solutions for increasing our options for providing transport of small teams of personnel into and out of harm’s way without increasing the number of personnel at risk (the aircrew) needed to move these teams,” the solicitation says. “There have been significant advancements in Short Take-Off and Landing (STOL) aircraft as well as traditional rotorcraft design that may provide solutions to the challenge.”

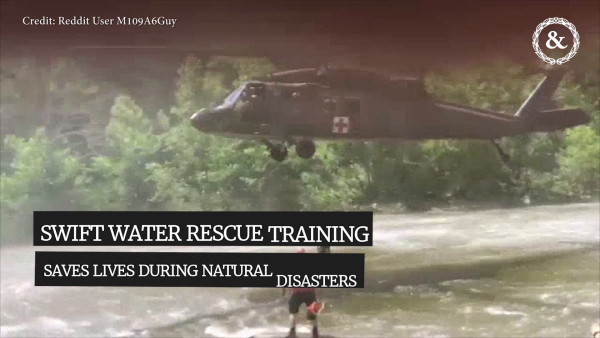

A U.S. Air Force HH-60G Pave Hawk helicopter hovers as aircrew members assigned to the 210th Rescue Squadron Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska, assess the scene upon arrival at the drop zone/air field, during simulated mass casualty combat training scenario July 30, 2014

(U.S. Air Force/Tech. Sgt. Efren Lopez)

That’s where the the business-focused SIBR and not, say, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) comes in: in a country where ride-sharing company Uber just enjoyed the most hotly-anticipated (and tumultuous) initial public offering in years, there’s an entire constellation of start-ups that could like fast-track an “on-demand” medevac and casevac solution.

“The significant private sector investment that could be leveraged for this military mission is the personal air vehicle (PAV) and urban air mobility (UAM) efforts,” the solicitation continues. “These efforts have been focused on urban operations for on-demand civilian transport and have many parallel design requirements to that desired under this SBIR but with some modifications to meet the military mission.”

Unmanned medevac and casevac solutions aren’t just on the Air Force’s mind.

The Army’s Medical Research and Materiel Command has been eyeing the benefits of deploying unmanned aerial drones in support of soldiers in combat since at least 2016, including unusual rotary-wing platforms like the lightweight DP-14 Hawk from Dragonfly Pictures, while the Navy and Marine Corps have been working on a joint Autonomous Aerial Cargo/Utility System (AACUS) effort in service of similar goals.

More recently, the Pentagon’s Joint Program Committee-6/Combat Casualty Care Research Program (JPC-6/CCCRP) posted an award notice in search of robotic platforms to “save the most lives with limited resources in austere conditions,” including “dense urban, subterranean, maritime, high-altitude, dust storm, and extreme environments.”

It’s worth noting that an effective platform for one-man air evacuations have long evaded the Pentagon’s grasp: “In the 1950s and 1960s, the U.S. Marines looked into both small single-person helicopters and ultra-light fixed-wing planes you could inflate like a balloon as potential alternatives to traditional helicopters,” as The War Zone observes. “None of these proved to be practical.”

But revisiting the prospect of a near-instant autonomous pick-up is alluring for Pentagon planners for good reason: the SIBR notice states that the new capabilities “must also support operations in the Indo-Pacific and Africa regions” beyond the Middle East — a noteworthy emphasis given that 2017 Air War College war games found that, unlike Iraq and Syria where the U.S. has enjoyed relative aerial freedom, North Korea’s robust air defenses would eliminate, or at least, degrade that advantage.

“Lift in the Pacific is always a problem and has been for years, simply because it’s just so big,” Lindsey Ford, a Asia Society fellow and former advisor to the Pentagon’s assistant secretary of defense for Asian and Pacific security affairs, previously told Task & Purpose. “To have the amount of lift you need to cover the tremendous amount of space, there is always a challenge, whether you’re talking about everyday operations or a unique medevac. Just think about that in the context of how many forces we currently have in the region.”

But there’s also another noble reason to pursue Uber for medevac, and it has to do with another pre-9/11 pilot shot down over eastern Europe who isn’t Goldfein.

In June 1995, Air Force fighter pilot Capt. Scott Francis O’Grady was shot down by a surface-to-air missile over Bosnia and Herzegovina while enforcing a no-fly zone, ejecting from his F-16C and spending almost a week dodging Bosnian Serbs until he was retrieved by U.S. Marines, a saga that would later serve for the inspiration for the 2001 action filmBehind Enemy Lines.

Look, Behind Enemy Lines may not be The Hurt Locker in terms of terrible military movies, but it’s still not a great film (see: 37% on Rotten Tomatoes!) If anything, the Air Force is working overtime to ensure that no pilot ever again becomes the basis for an Owen Wilson film — and that itself is a noble endeavor worth praising.