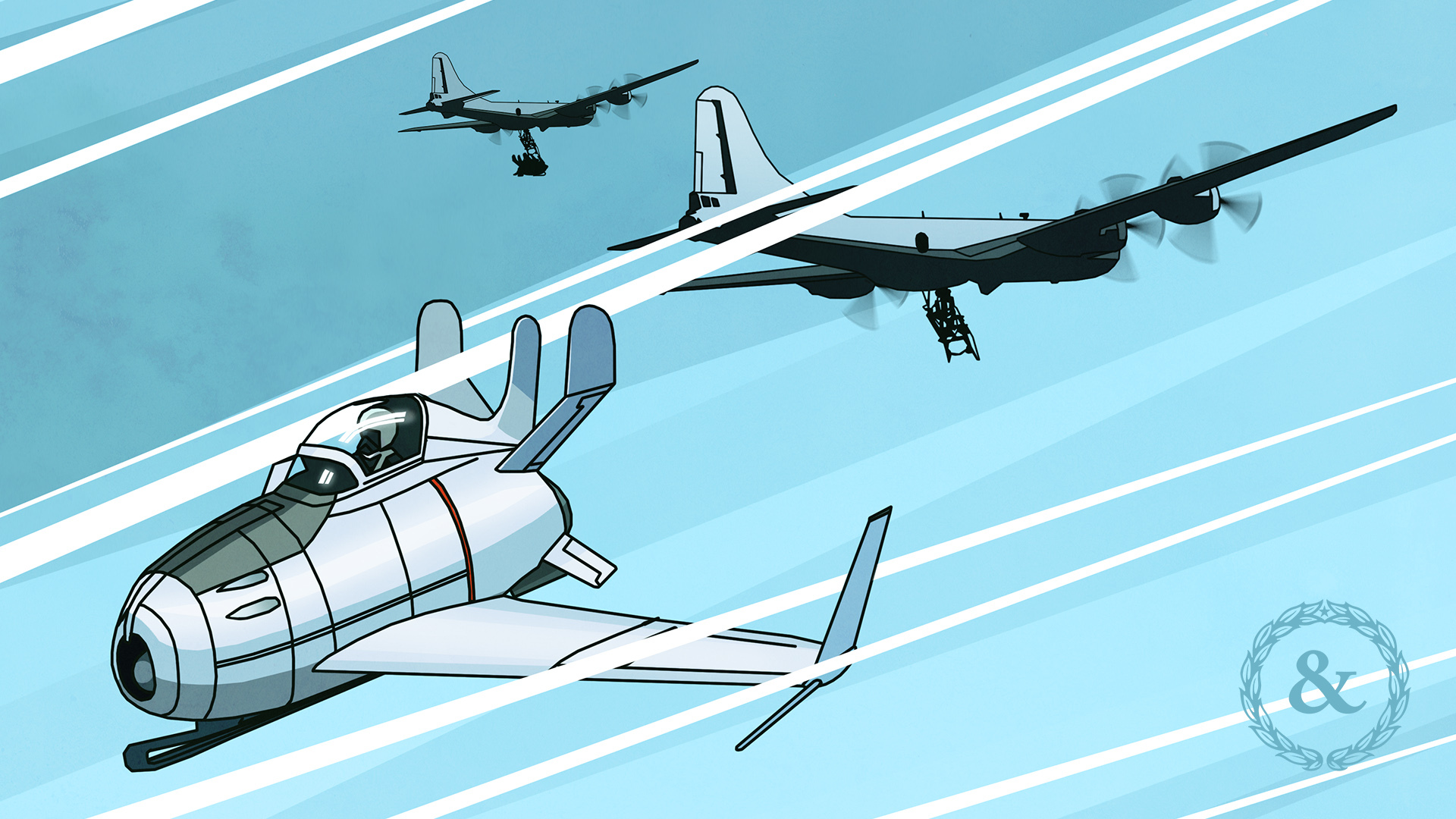

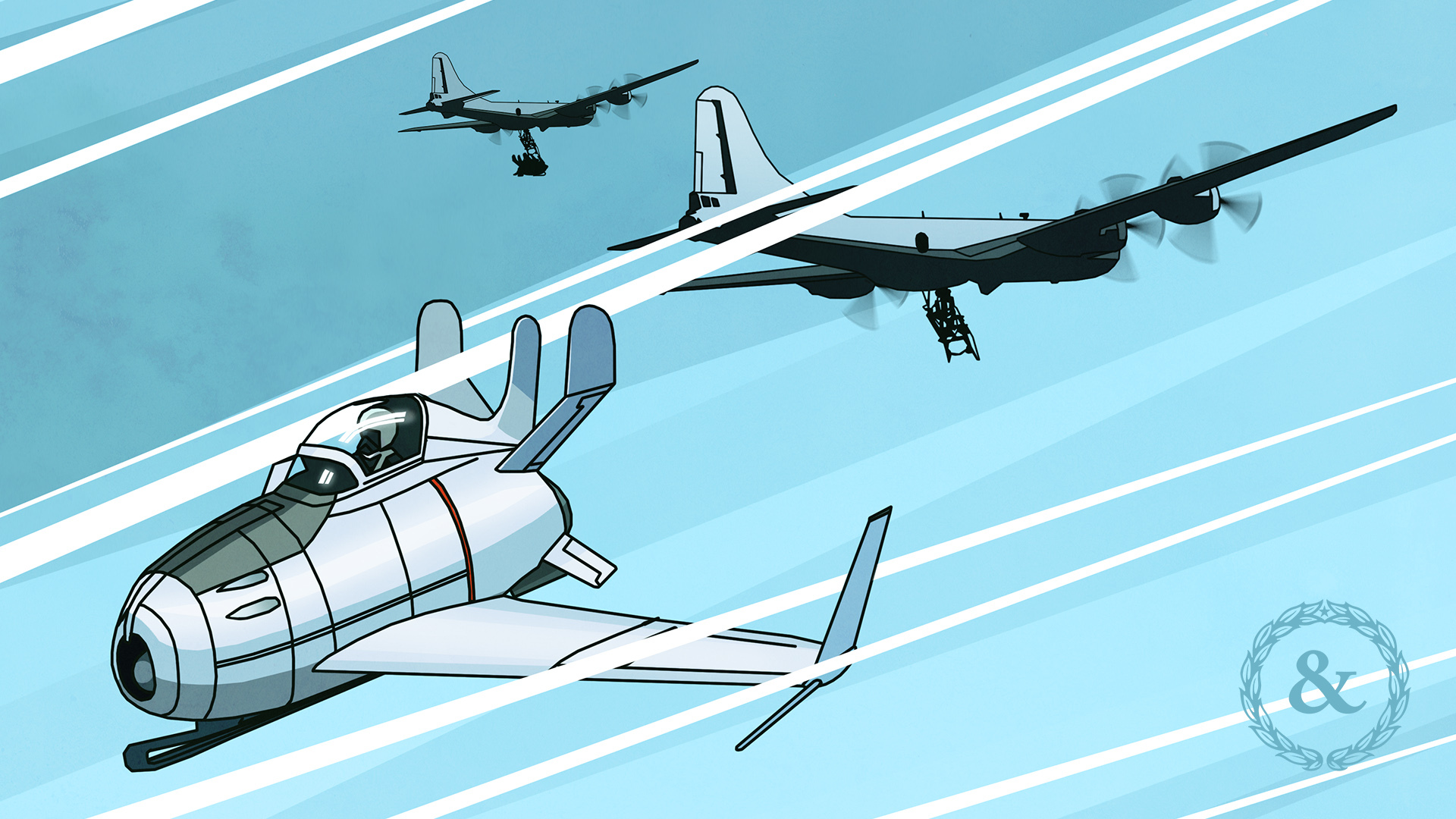

Imagine climbing through the bomb bay of a massive nuclear-capable Convair B-36 ‘Peacemaker’ bomber, flying high in the skies above a distant enemy target, most likely the Soviet Union. You strap yourself into a tiny, teardrop-shaped fighter jet, are lowered down into the sky, and take off as the best defense these bombers have.

Now imagine that you’re flying in this:

That was the plan for the McDonnell XF-85 “Goblin,” truly a testament to the fact that given enough money and time, the Air Force will try out just about any idea.

The Goblin measured just 15 feet in length, and with the wings folded up for transport was only five feet wide, making it the smallest jet fighter ever built. It was what’s known as a “parasite” aircraft and was designed to be carried by a larger bomber and then launched in the sky to protect against enemy fighters. It had no landing gear as, in theory, the Goblin would return to its parent bomber and reattach in midair.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

The Goblin arose as a very complicated solution for a fairly simple problem. In 1945, the Army Air Corps was developing the B-36 as a strategic bomber that could reach even the most distant targets. In contrast to the Goblin, the B-36 was one of the largest aircraft ever built. It could carry 86,000 pounds of nuclear or conventional ordnance and had a range of 10,000 miles. This also meant that it would far outpace any fighter escorts. Enter the Goblin.

The concept of “parasite” aircraft actually went back to some of the earliest days of aviation. During the First World War, Britain, Germany, and the United States all began carrying out tests to launch small fighters from airships, with the British in 1916 even carrying out the first successful midair launch of one plane from another. The Soviet Union was one of the biggest experimenters with the concept, and even used it briefly in combat during the early days of World War II, launching small fighters from bomber aircraft for raids on Romania. Still, planes were getting faster and more maneuverable, and airships were quickly becoming obsolete, which made the process of recovering the parasite aircraft incredibly difficult.

Although the concept remained impractical for decades, that wouldn’t stop the U.S. military from trying it out with the Goblin. The Army Air Corps ordered its first two prototypes in October 1945, and flight testing began in 1948. The Goblin weighed less than 4,000 pounds and was armed with four Browning .50 machine guns. The B-36 wasn’t ready yet, so the Goblin tests would be carried out using a heavily modified B-29 aircraft dubbed “Monstro.”

The first flight took place on Aug. 23, 1948. Manned by McDonnell test pilot Edwin Schoch, the Goblin was released at an altitude of 20,000 feet above what is now Edwards Air Force Base in California.

The aircraft handled fine in the air, but the same could not be said for reconnecting with “Monstro.” Schoch made two approaches, but experienced heavy turbulence. On a third attempt, The Goblin collided with the trapeze mechanism, damaging the cockpit. Despite losing his helmet and mask in the collision, Schoch managed to guide the Goblin down for a crash landing in a dry lake bed.

Two months later, Schoch finally managed to successfully dock the Goblin with “Monstro.” A week later, Schoch managed the maneuver again – after four unsuccessful attempts. The trapeze system then promptly broke, sending the Goblin back down for another crash landing.

Two more attempts were made in the spring of 1949, both of them unsuccessful. The Goblin – although it was described as having good flight characteristics when it wasn’t crashing into its parent bomber – was going nowhere fast.

And, like many aviation projects, the need for the Goblin was soon eclipsed by other technological advances. The same year the miniscule fighter was making its last flights, the Air Force was introducing its first aerial refueling aircraft. This was also a complicated maneuver, but it was much simpler than hooking a tiny jet aircraft onto a massive bomber at 20,000 feet.

In October 1949, the Goblin program was canceled, with the two prototype aircraft being consigned to museums as the kind of oddity that makes you go “what the hell is that?”

The Air Force would, of course, continue with launching jets from the B-36 for several more years, with the idea that larger fighters like the F-84 could be delivered far beyond their normal range to deliver tactical nuclear weapons, but the process of returning to the mothership was still too difficult to perform in anything other than optimal flying conditions and that program too was scrapped. Still, not many, if any, of these tests can match the XF-85 Goblin for sheer oddity.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Listen to Air Force fighter pilots intercept a ‘renegade’ plane intruding on Biden’s airspace

- An Army M1 Abrams tank dubbed ‘A Horse With No Name’ is riding through Poland

- Army Reserve major releases amateur porn video as part of political campaign

- Has the Army finally found a replacement for the Bradley Fighting Vehicle?

- Sgt. Maj. of the Army to leaders: Stop using behavioral health as a universal band-aid for problems

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.