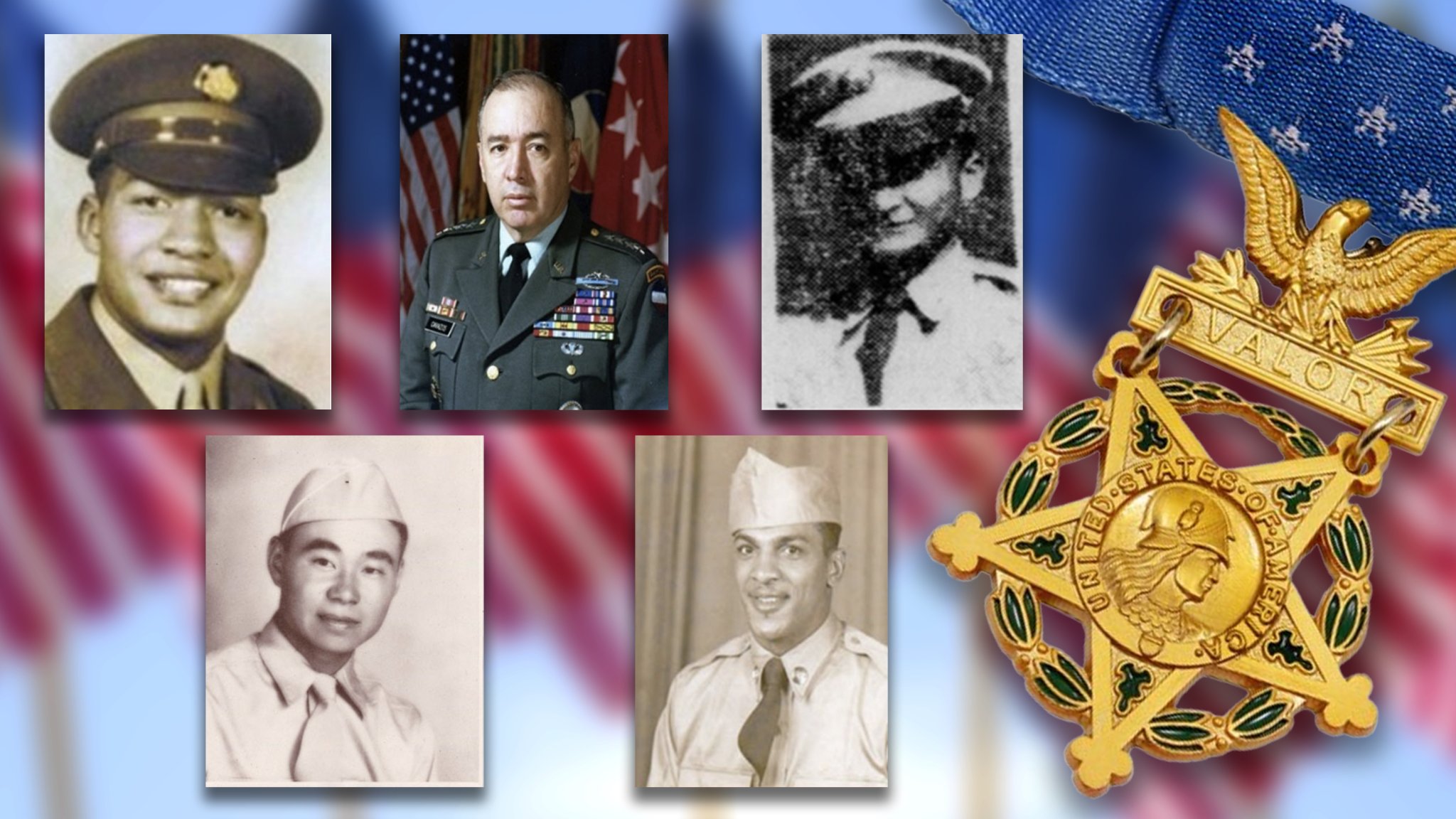

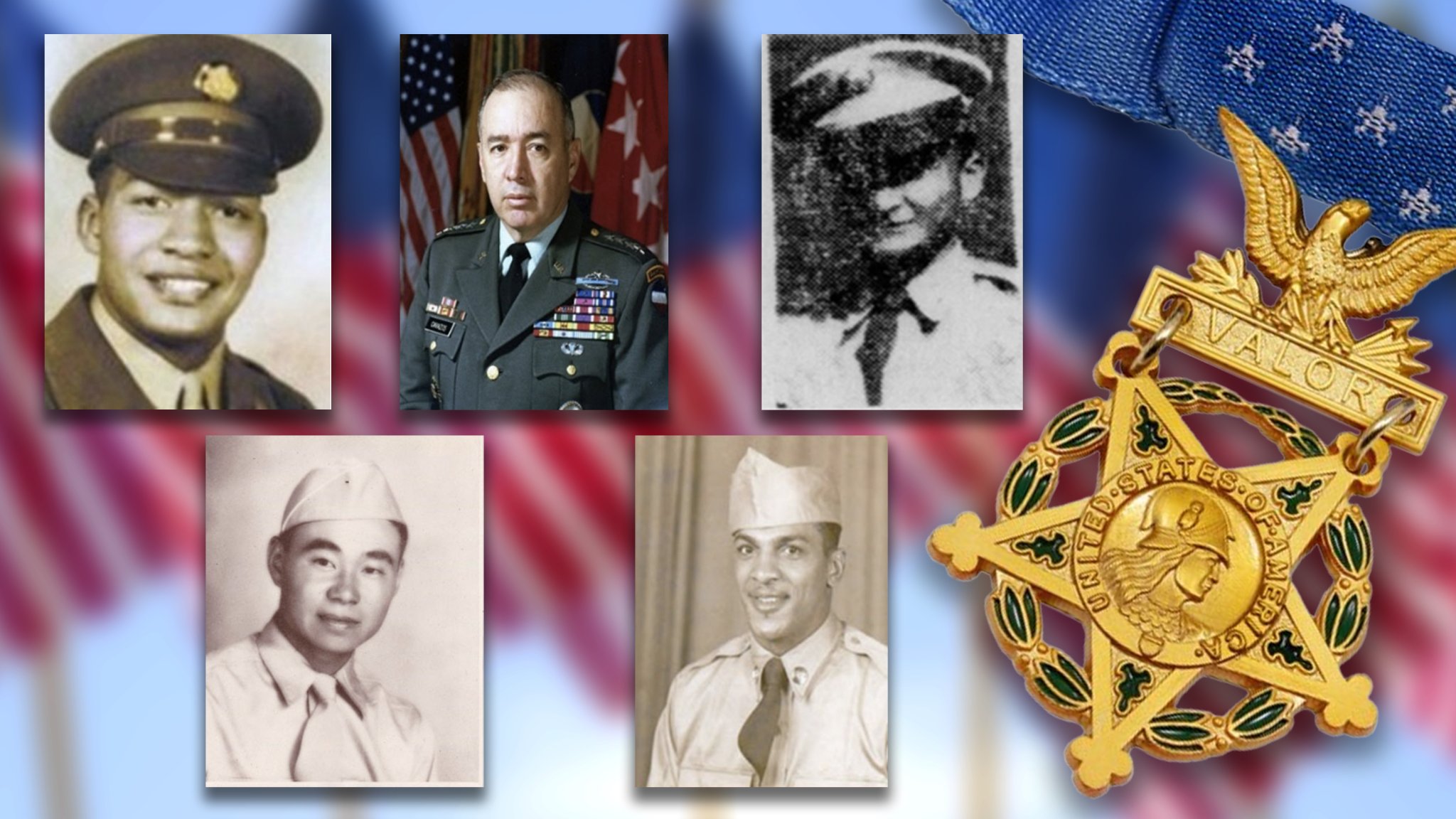

The Army general after which Fort Cavazos, Texas is named will be one of five Korean War veterans to posthumously receive the Medal of Honor on Jan. 3.

All five medals will be awarded today by President Joe Biden to the families of the recipients. Biden will also award the Medal of Honor to two Vietnam War veterans.

The soldiers are receiving the medals as upgrades of previous awards and as part of a measure included in the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act which waived time limits that required medals to be awarded within five years of combat action. Three of the new Medals of Honor were upgraded from Distinguished Service Cross awards.

Congress directed a review of awards for “certain Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander” veterans which led to the Medals of Honor for Pvt. Bruno Orig and Pfc. Wataru Nakamura and a review of “certain Jewish American and Hispanic American” veterans resulted in the upgraded Cavazos award.

Today, Gen. Richard Cavazos’ name is among the most widely known in Army history because of Fort Cavazos, the sprawling Texas base that was once Fort Hood. But Cavazos was one of the Army’s most important figures before his name was put on the base, for both combat valor as a young officer and later as the service’s first Hispanic four-star general.

The fight for Hill 412

In 1953, then-1st Lt. Richard E. Cavazos was a company commander for the 65th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division, near Sagimak, Korea when he evacuated casualties and led groups of men to safety under a barrage of enemy fire.

Tommy Cavazos, the general’s son, told reporters on a call in December that his father’s faith moved him to put the lives of his men ahead of his own.

“He was a man of deep faith, who loved his country, loved his family. He loved his soldiers, and it was that love, that selfless love, of which there’s no greater love, that drove him up the hill that night in 1953 to collect the men of his company and get them to safety,” Cavazos said.

Originally from Kingsville, Texas, Cavazos was born to Mexican American parents. His father served during World War I and became a ranch foreman. Cavazos attended college in Texas on a football scholarship until he broke his leg during his sophomore year. He then joined the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program and in 1952 he was commissioned into the Army.

On the night of June 14, 1953, Cavazos led his platoon on a mission to destroy an enemy installation that sat on an elevated spot known as Hill 412. The unit was met with heavy artillery fire and Cavazos helped defend Outpost Harry for “three arduous hours.”

Cavazos complied with orders from his chain of command to withdraw his unit but stayed behind to search for missing soldiers. He was able to locate five casualties and evacuate them one by one to a nearby hill where they were safely recovered. He also found a small group of soldiers who were separated from the main force and personally led them to safety.

Cavazos then returned to the battlefield for a second time to lead another group out of the line of fire. On the morning of June 15, after he determined that the battlefield had been cleared of his soldiers, he had his wounds treated.

After the Korean War, Cavazos commanded the 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment in Vietnam and eventually became the Army’s first Hispanic brigadier general in 1976. He was promoted to four-star general in 1982.

His son told reporters that Cavazos never sought or pursued the Medal of Honor, but his father’s former aide at Fort Hood, retired Lt. Gen. Randolph House was thrilled when he heard that the general was going to be honored.

“[House] was practically in tears. He thought it might happen, but he didn’t think it would happen in his lifetime,” Cavazos said. “It was just truly special to hear that reaction from him and we’re very, very grateful.”

Fort Cavazos, previously known as Fort Hood, is located a little more than 70 miles north of Austin, Texas.

Because of his extensive time as a commander at Fort Hood, Cavazos was picked as the new namesake for the base when it was one of nine Army bases renamed in 2022 from the names of Confederate soldiers.

With Cavazos’ award of the medal, the base is now one of a handful with former Confederate troop names that are now named for Medal of Honor recipients, including Fort Walker, Virginia (previously Fort A.P. Hill), Fort Johnson, Louisiana (formerly Fort Polk) and Fort Barfoot, Virginia (previously Fort Pickett).

“The definition of a hero is an ordinary person who does an extraordinary job. I believe my father would assert that he was very much a humble, ordinary man who was a husband, a father, and a proud American,” Tommy Cavazos said.

Gen. Cavazos will be honored with the Medal of Honor along with four other Korean War veterans: Pfc. Wataru Nakamura, Pfc. Charles R. Johnson, Cpl. Fred B. McGee and Pvt. Bruno R. Orig.

The men are receiving the medals as upgrades of previous awards and as part of a measure included in the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act which waived time limits that required medals to be awarded within five years of combat action.

Private First Class Wataru Nakamura

Despite spending months of his life during World War II in a Japanese internment camp in rural Arkansas with his family, Pfc. Wataru Nakamura, enlisted in the Army on April 22, 1944.

“At the time, a lot of the men in the camps wanted to prove their loyalty to the country and show the country that Japanese Americans belonged here,” his nephew, Gary Takashima, told reporters in December.

Nakamura, who was originally from Los Angeles, fought in Europe during WWII and was called back to duty as a Reservist when the Korean War started. He was assigned to the 38th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, near P’ungch’on-ni, Korea.

Around daybreak on May 18, 1951, Nakamura volunteered to repair his platoon’s communications line that connected them to the command post. As he traveled along the line, Nakamura came under fire from an enemy unit that surrounded his unit.. He rushed the enemy with a fixed bayonet and destroyed their machine-gun nest. After firing all of his ammunition, he resupplied from a unit that was ascending a nearby hill.

He returned to battle, killing soldiers in the last enemy-held bunker until he was killed by a grenade.

Nakamura was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

“Disregarding his safety, he made a one-man assault, silencing a machine-gun and its crew with his carbine and bayonet and destroying two other enemy positions with grenades,” according to the citation.

Takashima, his nephew, said that Nakamura was a humble man who would’ve reflected on his brave actions as part of his duties as a soldier.

“He would have been greatly honored to receive the Medal of Honor, but would have felt all of this was too much for doing what he was supposed to,” Takashima said.

Private First Class. Charles R. Johnson

Pfc. Charles Johnson, originally from Sharon, Connecticut, aspired to become a football player – even transferring high schools to get more exposure. Johnson played football for a season at Howard University in Washington D.C. before he was drafted into the Korean War, his nephew, Garry Trey Mendez, told reporters. During the war, Johnson served as a Browning automatic rifleman with the 3rd Infantry Division.

On the night of June 11, 1953, Chinese forces attacked his unit during a nighttime assault. Johnson was wounded from a direct hit on his bunker and a hand grenade, but administered first aid to more seriously wounded soldiers of his unit and even dragged one to a secure bunker. While providing life-saving aid, Johnson killed enemy troops in hand-to-hand combat. He also took it upon himself to resupply his unit with weapons and ammunition from a second bunker.

Johnson’s actions saved at least 10 other soldiers, including his Millbrook High School, New York classmate, Donald Dingee.

“They reconnected in a trench,” Mendez said, adding that Johnson and Dingee hadn’t seen each other since high school. “They ended up together on Outpost Harry and [in the] bunker together and he ended up pulling him out and pulling him to safety.”

Mendez never met his uncle, but he heard about Johnson’s heroism through the man he saved. At first, Johnson tried to pick his classmate up and carry him through the trench but Dingee said he was afraid they were too exposed and that he was too heavy to be carried over Johnson’s shoulder.

“He put him down and he dragged him. That’s actually the statue at their high school – is of him pulling [Dingee] through the trench,” Mendez said.

Mendez, sharing another story of his uncle’s “selflessness,” told reporters about one of his mother’s last memories of her brother. Johnson had called a girl named Juanita who he wanted to take on a date, unaware that his younger sister, also named Juanita, was on the phone line too.

“He had said, ‘hello, is this Juanita?’ And she said yes and he said, ‘would you like to go with me to the fair?’” Mendez said. “My mother, who idolized him, of course was like, ‘yes, yes, yes, I’ll go with you.’”

Even after he realized it was his sister on the other end of the phone, he still “passed up on the date” and took her to the fair, Mendez said.

“It was right before he left for Korea, and she talks about that all the time,” Mendez said. “It was just the most incredible time she ever had with her brother and it was the last time she really got to spend time with him.”

Juanita Mendez, who is Johnson’s only surviving sibling, will be present at the ceremony.

Corporal Fred B. McGee

Cpl. Fred McGee was originally from Steubenville, Ohio and enlisted in the Army on May 22, 1952. He served as a gunner on a light machine gun in a weapons squad near Tang-Wan-Ni, Korea.

On June 16, 1952, McGee supported his unit with heavy cover fire from an exposed position during an enemy assault on the platoon. His commander and several other soldiers were wounded during the fight so McGee assumed command and moved the squad to a more exposed position in order to have a clearer shot at the enemy. After their machine gunner was killed, McGee took over and ordered the remaining squad to withdraw. Instead of leaving with the unit, McGee stayed behind to evacuate the wounded and dead.

During the fight, McGee was wounded in the face but stood under enemy machine-gun and mortar fire. He first unsuccessfully tried to evacuate a company runner’s body and then successfully moved another wounded soldier to safety.

He was awarded the Silver Star and two Purple Hearts for combat action during the war.

When McGee’s story got back home, Famous Funnies, a comic book series based out of New York City, contacted him to write a series about his actions on Hill 528.

“My dad was proud of that too because comic books were such a big deal back then,” McGee’s daughter Victoria Secrest said in December.

His granddaughter Brandi Jones noted in an online essay that the story of a Black soldier featured in a comic would’ve been unique during an era where “racial tensions were high at the time of publishing.” However, Secrest, McGee’s daughter, told reporters that they made one glaring error after publishing.

In the comic book, McGee appeared white.

“They used his name, somewhat of his likeness and his actions in battle on Hilltop 528, but they forgot his melanin. They made him a white soldier,” she said. “I think it could have been inadvertently because they hadn’t seen a picture of him.”

McGee died on June 3, 2020 but Secrest said she fought for more than three decades to get his bravery recognized with a Medal of Honor. Secrest said she wrote letters to nine different Presidential Administrations and members of Congress going back to the ‘90s.

“If you want to get it done, you gotta keep going just like my dad kept going on Hill 528,” Secrest said.

Private Bruno Orig

Pvt. Bruno R. Orig, from Honolulu, Hawaii came from a family of military veterans. His father, step-father, older and younger brothers all served in the Army between World War I and the Vietnam War.

Charles Allen, Orig’s nephew, who served in the Army from 1981 to 2005, said his uncle decided to join right after high school despite growing anti-Asian sentiment during WWII.

“Because of the fact that he came from that military service background, the values of living in Hawaii, born and raised there, his parents being from the Philippines and all, he decided to enlist right out of high school,” Allen said. “I know that his mom asked him not to but he did anyway.”

Orig enlisted in August 1950 and served with the 23rd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, near Chipyong-ni, Korea. On Feb. 15, 1951, after returning from a wire-laying mission, Orig saw several of his fellow soldiers wounded from an enemy attack. He administered first aid to them and helped move them to safety.

After returning from one of the evacuation trips, Orig realized that most of the machine-gun crew had been wounded and volunteered to man the weapon. Orig fired on the enemy and allowed another platoon to withdraw without a casualty until the unit was overrun. Orig was found dead beside his weapon with several dead enemy soldiers in front of the gun.

Allen said his uncle’s actions and the rest of the Medal of Honor recipients’ heroism and bravery connects back to their upbringing and highlights the values they learned from their family. Allen’s own children have served and he himself once met Gen. Cavazos while still on active duty.

“He was already a retired four-star. He was a senior mentor, ‘Greybeard’ as we affectionately called him,” Allen said. “When he spoke, everyone listened and he impressed me then and I can imagine and read up on what he has done. He is definitely a true hero. You may call him an ordinary person, but he is indeed a hero in my eyes.”

Update: 1/3/2025; This article was updated after publication with additional information from the Army about the award upgrade process.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Special Forces soldier dies in non-combat incident at Eglin range

- A Marine’s disciplinary record from 100 years ago reveals rank-and-file life as much the same

- Navy shoots down its own F/A-18 in Red Sea fight

- The Coast Guard is building up its Arctic fleetCoast Guard pilot receives top flying honor for helicopter rescue