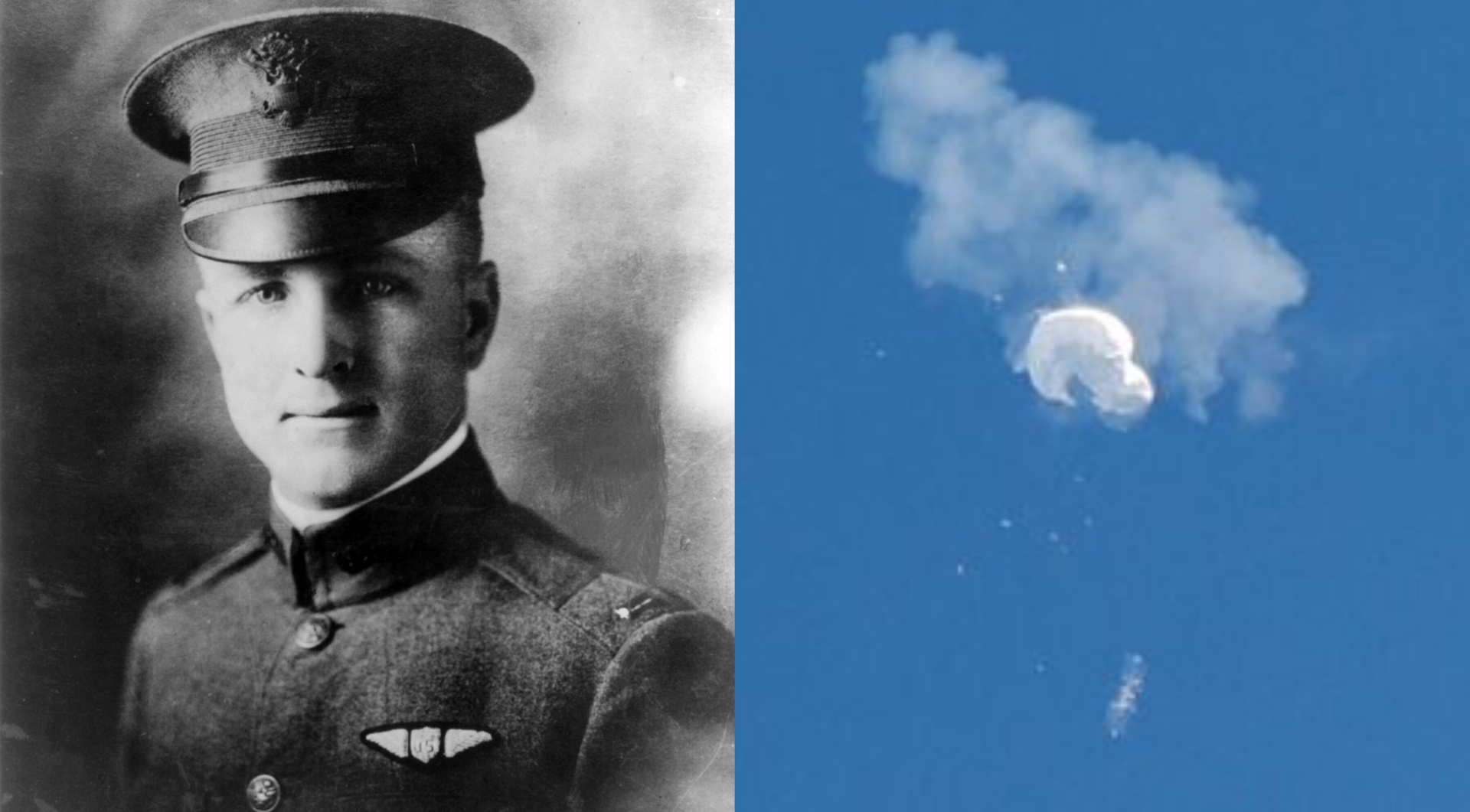

The saga of that Chinese spy balloon floating across the continental United States at an altitude of about 60,000 feet came to an end over the weekend after a pair of F-22 Raptors from the 1st Fighter Wing at Langley Air Force Base, Virginia sent the balloon plummeting into the ocean with a single AIM-9X Sidewinder missile.

The balloon’s downing was the first air-to-air kill ever for the Air Force’s F-22 Raptor, which made its combat debut in 2014 by bombing an Islamic State group command center in Syria, and the Navy is currently working to recover its debris from off the Carolina coast.

While downing a balloon is an unlikely kill in the 21st century, the call signs used by those jets, as well as a second pair of F-22s, were a nod to an American fighter ace who made his name doing just that during World War I

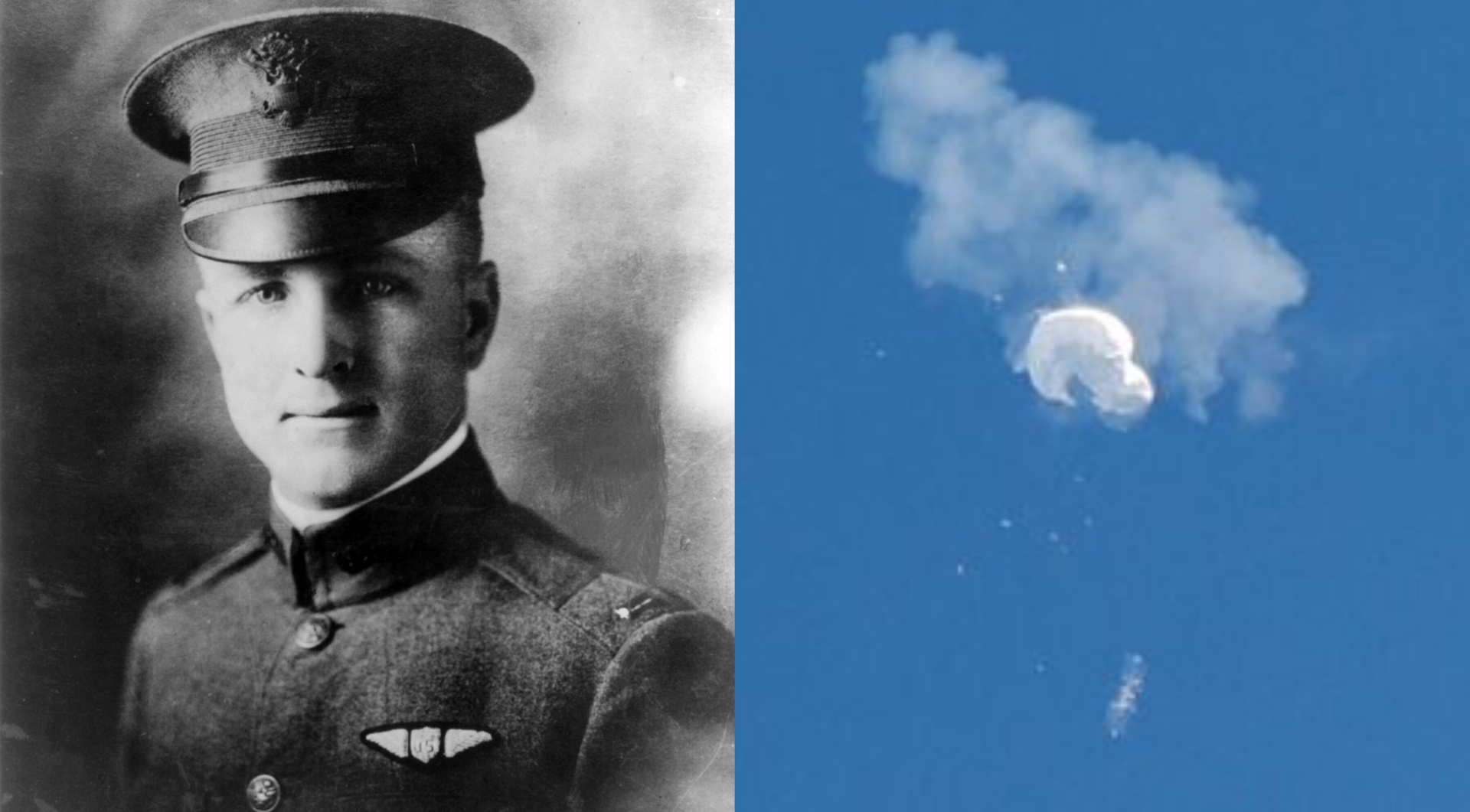

That ace was 2nd Lt. Frank Luke Jr., the so-called “Arizona Balloon Buster” and the first U.S. Army Air Service airman to receive the Medal of Honor who earned his nickname by shooting down 14 German observation balloons over France in less than three weeks.

“The call sign of the first flight was Frank01. The second flight of F-22s was Luke01,” said Air Force Gen. Glen VanHerck, commander of United States Northern Command on Monday. “Frank Luke, Medal of Honor winner in World War I for his activities that he conducted against observation balloons. So, how fitting is it that Frank01 took down this balloon in sovereign airspace of the United States of America within our territorial waters.”

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

Luke enlisted in the Army Signal Corps in September 1917, receiving his pilot training and commissioning in January 1918. He excelled in training, completing his initial flying course two weeks early and graduating first in his class at flying and second in gunnery at the U.S. Aviation Center Instruction Center in Issoudon, France, when he arrived on the continent in the spring of 1918.

While Luke wrote to his sister that “I will make myself known or go where most of them do,” he initially made himself known for his cocky attitude, which was not well received by many of the other pilots of the 27th Aero Squadron where he was assigned. Initially detailed as a ferry pilot, on one of his first combat missions in August he broke away from the formation to chase after a group of German planes, according to Air and Space Forces Magazine. He did the same thing later that month, but without any witnesses, his claim of having shot down a German plane went ignored.

In September, as the American Expeditionary Force prepared for one of its final major offensives of the war around the town of St. Mihiel in northeastern France, Col. William Mitchell, commander of all American air combat units in the country, ordered a new mission: shooting down German observation balloons. The balloons, while carried aloft by highly flammable hydrogen, were heavily defended from the ground with anti-aircraft cannons and machine guns. To counter the balloons, all squadrons selected pilots to fly in pairs, one high and one low, to attack the balloons. Among them was Luke.

Flying from the town of Rembercourt, he recorded his first balloon kill on Sept. 12, going so far as to land at a nearby American balloon site and collect a pair of written statements to ensure he would get credit. On Sept. 14, he shot down another two balloons, then three more the next day. On Sept. 16, with Mitchell observing, Luke and his wingman, Lt. Joseph Wehner, downed another pair of balloons. And two days after that, Luke scored five kills in just a matter of minutes – two balloons and three planes – although Wehner was killed in the engagement.

In just a week, Luke had become the leading American ace of the war, which garnered him both plenty of publicity and not-so-positive attention from some of his superiors. When he returned from five days of mandated leave on Sept. 25, now without a wingman, he began taking off on missions without filing a flight plan. Still, the victories continued: on Sept. 28, he shot down another balloon and ground-attack plane.

The next day, Luke’s squadron commander wanted him grounded for insubordination but was overridden by the group commander, who authorized another mission. Taking off at dusk, witnesses on the ground reported three downed balloons, bringing Luke’s tally of victories to 18, including 14 balloons. He didn’t return from the mission, however, and was reported as missing in action.

His habit of flying alone meant that Luke’s ultimate fate was shrouded in mystery. He was posthumously recommended for the Medal of Honor a week after the armistice in Nov. 1918. A couple of months later, when Luke’s body was identified, local witnesses were interviewed, although the officer compiling the report spoke no French. The witnesses claimed that Luke had strafed German positions, crashed, and continued firing at German soldiers on the ground until he was killed. But when a second officer, this time able to speak French, re-interviewed some of the witnesses, they said no shots had been fired.

A version of the more heroic recounting of events eventually became part of Luke’s Medal of Honor citation, which reads that, “Forced to make a landing and surrounded on all sides by the enemy, who called upon him to surrender, he drew his automatic pistol and defended himself gallantly until he fell dead from a wound in the chest.”

Regardless of his ultimate fate, Luke’s confirmed accomplishments made him one of the notable American figures of the war, second only to Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker, who finished the war with 26 aerial victories, in terms of fame as a pilot. Today, Luke Air Force Base is named for the “balloon buster.” Now, more than a century later, at least one Air Force pilot can join Luke as a certified “balloon buster” — for now.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Marine shown fighting with San Diego hotel staff in viral video charged with assault and battery

- Air Force cadet died of blood clot in lung, autopsy finds

- Airmen prepare to bid farewell to beloved ‘Big Sexy’ refueling tanker after 30 years of service

- The US appears to have used its missile full of swords in an airstrike in Yemen

- What the chances of a war between the US and China actually look like, according to experts

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here.