Peter Debbins claims he was a patriot seeking adventure when he entered U.S. Army officer training in July 1998. But the soldier, who became an elite Green Beret and later applied to the Central Intelligence Agency, lived a double life as a Russian mole and gave Moscow the names of his Special Forces colleagues years later.

“I feel personally betrayed. My Detachment Commander sold me out to Russia,” a subordinate said of Debbins in a sentencing memorandum recently filed in Virginia. “It sounds crazy and almost unbelievable.”

Debbins, 46, was sentenced on Friday to more than 15 years in federal prison after admitting he passed secrets to Moscow for roughly the same amount of time. Yet despite his former teammate’s disbelief, court documents paint a troubling picture of a young, self-described immigrant “son of Russia” who grew up in Minnesota and came to be known by Russia’s GRU military intelligence service by the codename Ikar Lenikov without American intelligence knowing for more than two decades.

“Debbins betrayed his oath as an Officer, his Team, and the Special Forces community,” said Maj. Gen. John Brennan, the commander of the 1st Special Forces Command. “By putting his own loyalties first, and providing Russia information about the Special Forces, he risked lives of those he served with and, potentially, future Special Forces Teams.”

Indeed, Debbins’ former subordinate in the Germany-based 1st Battalion of the 10th Special Forces Group believes he will have to look over his shoulder for the rest of his life. “I will always fear for the safety of friends and family who could be targeted for their association with me,” he wrote.

But how did an American become an Army officer, join the ranks of one of the military’s most elite special operations units, and secretly serve Moscow for so long without being detected? And what motivated him to betray his closest brothers in arms and the country of his birth?

“The answer unfortunately is extremely complicated and is why Mr. Debbins is involved in one of the most unique espionage cases in modern times,” his attorney argues, describing Debbins as a naive, patriotic American who was duped. “To put it simply, Mr. Debbins was and is an intelligent yet troubled man who was taken advantage of at a young age by a foreign government and could not find a way out.”

‘The Russian GRU ruined my honor and potential as an American’

The story, as Debbins and his supporters tell it, begins in the former Soviet Union. Debbins’ mother Victoria survived Joseph Stalin’s murderous famine in Ukraine as a child only to be taken by the Nazis into slave labor camps. Eventually, she and Debbins’ father made it to the United States where Peter, one of the youngest of 17 biological and adopted children, recalled having fond memories of growing up in Minnesota. He was an avid churchgoer and was whip-smart, graduating from high school at the age of 16 and earning the nickname “the professor.” He was a “bookworm,” his brother Josef said.

He was also extremely loyal. Judy Makowske, a longtime family friend from church, recalled how Debbins came to a funeral for someone he only worked with briefly nearly two decades prior so that he could “be there for those who have always been there for him,” as Debbins’ attorney wrote.

“Peter has been a true blessing in my life,” said Michael Hansen, a Marine Corps veteran and friend who had “nothing negative to say” about Debbins even after learning of what he was accused of. In fact, 15 friends, colleagues, neighbors, and his priest described the husband and father of four as a respectable family man with integrity.

“Peter has shown himself to be an honorable man who cares more about his family than himself who is taking responsibility for his past mistakes and would not repeat them,” wrote Father Richard Carr, a priest in Gainesville, Virginia who knew Debbins since 2016 but came to know him more after his arrest. “I would not write this letter unless I firmly believe that Peter poses no security threat to our nation and wants to live the rest of his life as a good American citizen,” Carr wrote.

In a letter to the judge seeking leniency, Debbins wrote that he was troubled during his childhood by his mother’s and siblings’ emotional pain. Some of them suffered from schizophrenia, Down’s Syndrome and other conditions. When he was 10, Debbins witnessed his mother’s slow decline and death from Parkinson’s disease. And perhaps worst of all, for most of Debbins’ life, he was hiding an attraction to men that he called the brutal suppression of his “true self.”

Debbins claimed he was homosexual and collaborated with the GRU agents for fear of blackmail: He was afraid they would reveal that he was gay, which, at the time, would have likely ruined his career.

“I believe they knew of my [same-sex attraction] from effeminacy, an encounter I had, and visits to adult stores,” wrote Debbins of why he felt compelled to cooperate in his first meeting with the GRU in 1996. “I did not disclose my initial meeting because I feared the Army would learn of my [same-sex attraction] and pathologies, ending my nascent military career in shame,” he added, noting a Clinton administration policy known as “don’t ask, don’t tell” that resulted in an estimated 14,000 military service members being discharged because of their sexual orientation.

“The Russian GRU ruined my honor and potential as an American,” Debbins wrote.

The other side of the story

Peter Debbins could very well have been blackmailed into selling out his country by the Russians. He wouldn’t be the first.

An FBI guide from the 1980s describes how an attractive woman approached a U.S. official in the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The American unsuspectingly chatted and drank vodka with the female KGB agent before he was taken to a room where they were filmed having sex, leaving him in a “classic, compromising situation.”

But as the guide argues, the only defense against such blackmail is to immediately fess up and report it. Otherwise, you can easily end up in the pocket of a hostile intelligence service.

“The two primary ways in which they recruit people is either through bribery or blackmail. … They find ways of threatening people through compromising information,” Bill Browder, an American hedge fund manager with a decade of experience in Russia, said in 2017.

“The most important step is to have all such contacts reported to the Security Officer,” the FBI guide urges. “This allows the Security Officer to monitor the contacts and protect the employee’s record. It also enables the officer to detect recruitment operations as they develop.”

But unlike the model U.S. official from the Cold War who came clean, Debbins didn’t report his contacts. When Debbins visited Russia in 1996, prior to serving on active duty, a Russian intelligence agent contacted him and he agreed to meet. “They discussed the defendant’s participation in the ROTC program and his plans for military service,” according to a statement of facts agreed upon by the federal government and Debbins, which lays out a different scenario: That from around December 1996 to January 2011, Debbins was a willing and able Russian spy for the entirety of his military career and for years afterward.

“Debbins betrayed this nation and his fellow serviceman, putting Americans and our national security at risk by providing national defense information to Russia’s Intelligence Service,” said Steven M. D’Antuono, Assistant Director in Charge of the FBI Washington Field Office. “Despite being entrusted to protect his colleagues and U.S. national security, he chose to abuse this trust by knowingly providing classified information to one of our most aggressive adversaries.”

Despite his midwestern birth, Debbins said he “developed an interest in Russia” partly due to his mother’s heritage. In 1994 when he was 19 years old, he visited the country for the first time as an exchange student. A roommate introduced Debbins to a girl from the industrial city of Chelyabinsk whose father, a colonel in the Russian Air Force, worked at a nearby base.

“We began to correspond by letters and he came again in 1995,” Debbins’ wife Yelena told the judge. “We knew that we would be together and have a big family. That year, I started university, and when Peter came again in 1996, he proposed to me.”

Debbins was then a student at the University of Minnesota in the pipeline to become a military officer through the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC). In the same year he met Yelena, he received a Secret security clearance. And by December 1996, he was engaged to be married to a Russian woman and meeting with Russian intelligence operatives for the first time.

“The defendant subsequently had at least two meetings with one or more additional Russian intelligence agents in December 1996, including an agent of the Russian intelligence service who was from Samara, Russia,” court documents state. “As a cover for their meetings, the Russian intelligence service directed the defendant to tell his girlfriend [Yelena] that he was meeting with a professor on campus.”

The Russian intelligence officers wondered about Debbins’ ambitions and asked him what he planned to do in the Army. They agreed on politics: Debbins described his views as “pro-Russian and anti-American,” according to court documents. Debbins’ political leanings were almost certainly a boon for the Russian intelligence operatives. But had Debbins informed the Army of his connections to Russia? The 21-year-old future Army officer assured them he was being “very discrete.”

Debbins said he was a “son of Russia” who wanted to learn more about the country. But a Russian operative wanted to test him first: What were the names of four nuns at the Catholic church he frequented? Foreshadowing the later betrayal of his elite teammates, Debbins dutifully complied.

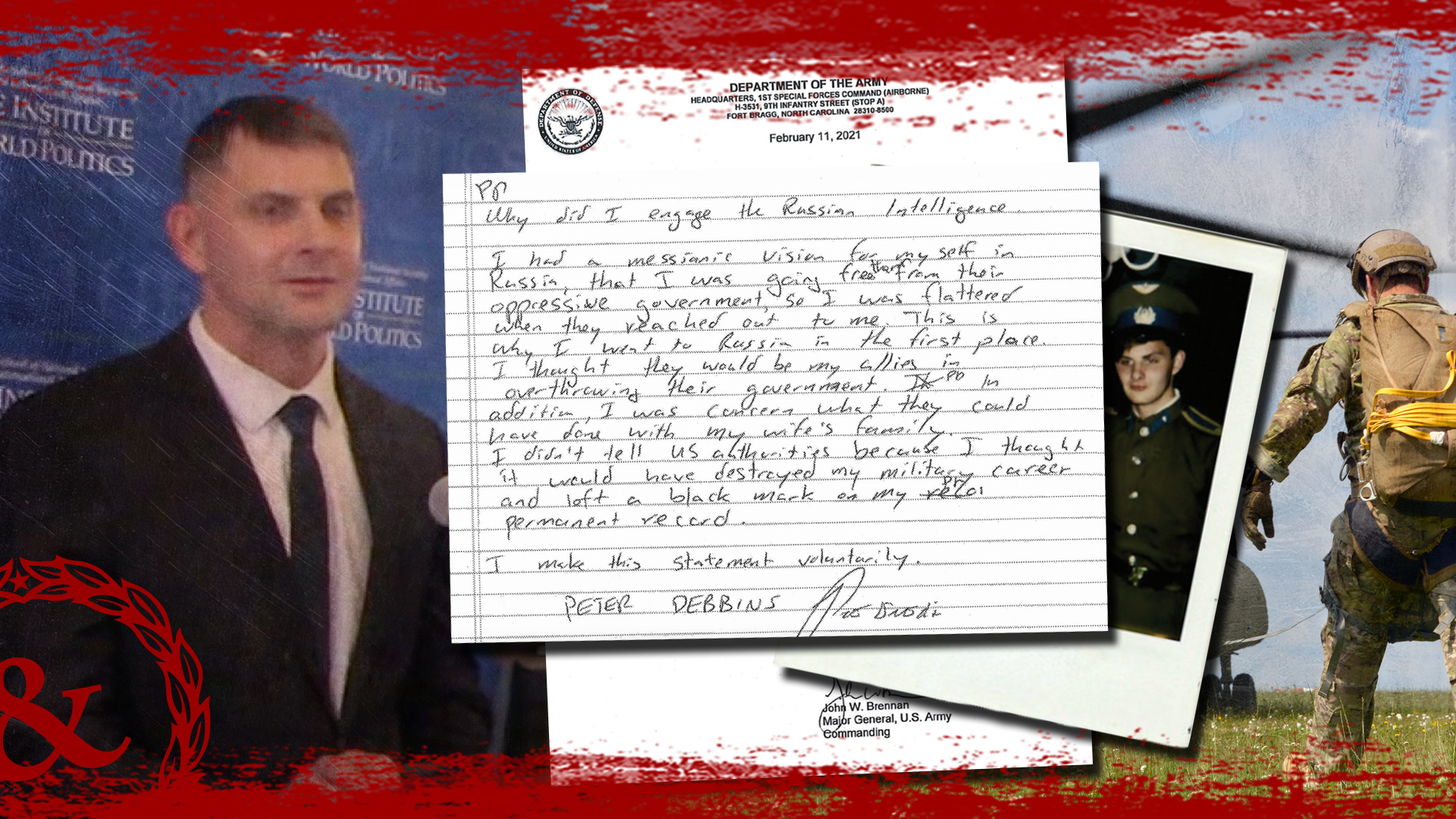

“I had a messianic vision for myself in Russia, that I was going [to] free them from their oppressive government,” Debbins claimed in a handwritten July 2019 statement listing his contacts with Russian intelligence. “So I was flattered when they reached out to me. This is why I went to Russia in the first place. I thought they would be my allies in overthrowing their government.” The statement excluded any mention of his sexual orientation — which Debbins later claimed was used to blackmail him into cooperating.

Debbins returned to Minnesota in 1997 and graduated in September before heading back to Russia that same month. He was known to the U.S. government as 2nd Lt. Peter Debbins by that point. But one month later, he picked up a new name known only to Russian officials: Ikar Lesnikov. At a meeting in an office on a Russian military base in Chelyabinsk, Debbins signed a statement as Lesnikov that said he wanted to “serve Russia.”

The Russians entertained their American turncoat for several days at a country resort in Russia’s Volga region. They gave him a telephone number he could use to reach them and encouraged Debbins “to serve well in the U.S. Army.”

He did exactly that. In July 1998, Debbins was assigned as an Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear officer with the Army’s 4th Chemical Company for a deployment to South Korea, according to Army records and court documents. He reported his unit’s mission, makeup, and equipment to Russian intelligence. Then in April 2001, he was reassigned to Fort Polk, Louisiana as a lieutenant with the 7th Chemical Company. Debbins again told the Russians about his unit, but during one meeting, Debbins informed them that he was joining Special Forces.

He received encouragement from a Russian intelligence officer. As a regular army officer, he was of no use to Moscow, the intelligence officer told Debbins. He gave Debbins $1,000 as a token of gratitude although the soldier initially refused since “he had a true love for Russia,” Debbins said. He ultimately accepted the money and signed for it with his code name.

By June 2003, Debbins had completed airborne and special operations training and was a captain assigned to the 1st Battalion, 10th Special Forces Group. It took only a couple of months for him to check in with his foreign handlers. In August on another trip to Russia, he called the telephone number given to him by the GRU and arranged a meeting at a hotel. He met two Russian intelligence officers he had never seen before.

They wanted to know how Debbins’ unit worked, and he complied, laying out the location and structure of the unit and providing details about the soldiers he served with and what they did. “They encouraged me to pursue [a Special Forces] career,” said Debbins, who accepted a gift of cognac and a Russian army uniform. As Debbins wrote, they advised him to avoid polygraphs and offered to train him on how to defeat them.

Yet all the foreign travel and meetings with intelligence agents apparently did not raise much suspicion on the American side, though military intelligence officers did interview him twice to ask questions about his travels to Russia in 2000 and 2003. Nevertheless, Debbins’ security clearance was upgraded in 2004 to Top Secret, allowing him access to secure compartmentalized information.

From then on, Debbins commanded a Special Forces A-Team based in Stuttgart, Germany. A professional resume filed as evidence in the case shows he also served as a company executive officer who served in Bosnia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. Yet Debbins made a critical mistake in Azerbaijan that cost him his command: He brought his wife to the country and gave her a U.S. government-issued cell phone. Debbins told the judge he “became reckless” with his military career since he felt “trapped” by his double life.

The suspension of Debbins’ clearance and his relief ended his career in the Army, but it did little to stop his other career as a double agent for Russia. By November 2005, Debbins was honorably discharged from the Army and back living in Minnesota. He began working in marketing for a Ukrainian steel manufacturer while still serving in the military’s inactive ready reserve and then moved on to work for a transportation company in St. Paul. But in the fall of 2008, he returned to Russia to meet several times with intelligence officers. Debbins wanted to explore business opportunities in the country and thought they could help.

In exchange, the ex-Green Beret officer provided information about his former team’s experience in Azerbaijan and Georgia, a country Russian troops invaded in August 2008 in a five-day conflict that brought them within striking distance of the capital city. “The defendant intended and had reason to believe that this information was to be used to the injury of the United States and to the advantage of Russia,” says the statement of facts.

Debbins also revealed the names and information of six of his former Special Forces colleagues, believing the Russians might use it to co-opt other Green Berets. Debbins “identified … at least one specific Special Forces team member whom he thought they could approach” and identified a military intelligence officer he had previously worked with.

What motivated him to do it? Debbins said during sentencing that he thought his teammates’ names were already known and claimed he told the Russians they were “faithful to America.” But that contradicts the statement of facts: He was “angry and bitter about his time” in the Army and thought America needed to be “cut down to size,” Debbins told his Russian handlers.

Debbins returned to the United States in September 2008 and submitted paperwork to renew his security clearance. Even as the government was presumably looking into his background, Debbins sent emails to a Russian intelligence officer who encouraged him to return to Russia and even offered to finance the trip. Debbins declined.

Still, Debbins’ background raised red flags in the federal government when it was learned he would receive a Top Secret clearance once again. But it wasn’t enough to prevent him from serving in highly sensitive U.S. intelligence positions for the next decade. In a letter granting his clearance in January 2010, the Army expressed concerns about his unexpected relief of command in Azerbaijan, business connections and the fact that his father-in-law was a colonel in Russia’s military. Ironically, the letter cautioned that foreign intelligence services could exploit those weak points in his background and urged him to report any foreign contacts.

Debbins spent about two weeks in Russia later that year. In meetings with his Russian handlers, Debbins emphasized that he wanted to pursue business in Russia, but the GRU had other ideas: They suggested he rejoin the U.S. federal government. And on Jan. 3, 2011, Debbins emailed a Russian businessman with intelligence connections to tell him he had moved to “the capital” and was working on a mutual business matter.

In fact, Debbins moved to northern Virginia and began applying for jobs in the intelligence community. The former Green Beret applied for four positions with the CIA in December 2010 and then for 17 positions with the National Security Agency in January 2011 which would have provided him access to far more sensitive information that, if disclosed, would have been disastrous to national security.

“Debbins, a serious security vulnerability considering his history of espionage activity, put national security further at risk by lying and deceiving his way into those positions,” prosecutors wrote in a sentencing memo.

In the end, Debbins was unable to join the NSA, but he did land a position exceptionally close to the agency’s headquarters on Fort Meade, Maryland in January 2011, according to his resume. Debbins provided direct analytical support to counterintelligence cyber operations as a senior Russian cyber analyst for the Army’s 902nd Military Intelligence Group until March 2014, he said of his accomplishments, adding that he established a standard operating procedure for training Army linguists and boasted that some of his recommendations were adopted by the Department of Justice.

Remarkably, Debbins worked for an Army unit that countered foreign intelligence and insider threats like him. And then he used that position as a launchpad for other jobs with the Defense Intelligence Agency and private defense contractors such as Booz Allen Hamilton and CACI.

“Debbins did not reveal his contacts with the Russian intelligence agents to law enforcement until after he failed a polygraph as part of a security clearance reinvestigation in early July 2019,” prosecutors wrote.

But the story seems to come to an abrupt end long before that, according to the Justice Department. Although Debbins was not arrested until August 2020, prosecutors charged him with an espionage conspiracy involving Russian intelligence operatives that only lasted until January 2011. Why?

Unanswered questions

It is likely that many questions will remain unanswered, perhaps forever. On Nov. 18, 2020, Debbins pleaded guilty to the charges just three months after his arrest and began to assist the government in the investigation, prosecutors said. But since his crimes dealt with classified information and he was never tried, key details are hidden behind blacked-out redactions and court documents filed under seal.

Between August and September 2008, for example, Debbins described a meeting in Chelyabinsk with a Russian intelligence officer named Ivan and another he called Mr. X. Though he had left the Army, Debbins told them how he and his Special Forces team had been “Rumsfeld’s spies” at the American embassies in Azerbaijan and Georgia, where he reported poor relations between “the Agency” — presumably the CIA — and the State Department. The next part of Debbins’ handwritten statement is redacted, but then he admits: “Gave first name of station chief.” (Station chief is the common shorthand for the Chief of Station, the CIA official in charge of intelligence operations in a foreign country.)

No charges were filed against Debbins for this apparent disclosure, which likely put the life of the CIA station chief in danger. Government officials also made little note of an entry in his timeline of Russia contacts on May 2012 in which Debbins discussed his father-in-law receiving a visit from the GRU. Yet they mention that “even after 2010, Debbins continued lying and concealing his contacts with the Russian intelligence agents while applying for positions in the U.S. intelligence community,” prosecutors wrote in a sentencing memo. But Debbins, who lied repeatedly for more than a decade about his crimes, “claimed that his conspiracy with Russian intelligence agents did not continue past 2011.”

It’s hard to imagine that Russian intelligence would abandon an asset that it cultivated over 15 years. Especially since Debbins gained access to more valuable intelligence each year since 2011. Debbins boasted of having access to highly classified databases throughout his time with the 902nd Military Intelligence Group. Then he moved on to another contract role with the Defense Intelligence Agency in April 2014, where he said he “supported and helped shape DIA’s cyber counterintelligence platform.”

Debbins left DIA after almost two years. In January 2016 he took on a new role developing a cyber threat intelligence program for agents in the Defense Security Service (now called Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency), which became the standard for the entire intelligence community, according to his resume. That job ended in September 2017. A month later, Debbins picked up another in Sterling, Virginia in the DIA’s regional training facility, where he said he worked on cyber training programs for NATO and the U.S. European Command.

Interestingly, prosecutors sought a 17-year sentence in part “to deter and preclude Debbins from fleeing to Russia and divulging more classified information from his time in the U.S. intelligence community,” they wrote. Meanwhile, they have a huge amount of evidence which includes, “among other things, data from nineteen electronic accounts and dozens of electronic devices and storage media seized” from Debbins’ residences.

“The government has advised the Court that some of the evidence in this case was obtained from foreign nations and that it might need to call foreign witnesses to testify at trial,” prosecutors wrote.

Debbins said he now regrets his decision to visit Russia because of the way its nefarious government views people like him as expendable commodities, he wrote. As his attorney tells it, Debbins is filled with remorse for the pain and suffering he caused his country and his family. But Debbins’ own words tell a different story. On July 11, 2019, under the watchful eye of an FBI agent, Debbins penned his reasons for hiding his secret life in Russia in purely selfish terms: “It would have destroyed my military career and left a black mark on my permanent record.”

Despite Debbins’ apparent whitewashing of his past, prosecutors suspect he did more than he admitted. “Debbins casts himself as the victim in this case,” prosecutors wrote, arguing that his letter to the judge seeking leniency contained statements that were incompatible with those he stipulated in his statement of facts. They focused on his claim that he “had no malicious intent” despite admitting to espionage “with the intent and reason to believe” that it would injure his home country.

“Rather than expressing remorse for acting with this criminal intent, Debbins attempts to disclaim it altogether in his letter to the Court,” prosecutors wrote, “which is incompatible with acceptance of responsibility.”

Debbins was criticized for seven additional pages by prosecutors. But we can’t see the words behind the full-page redactions. Some secrets will remain so, at least for now.