In the 1950s, Jerry Pournelle imagined the military equivalent of the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Toiling away as a Boeing operations researcher in the afterglow of the Manhattan Project and the Soviet Union’s First Lightning nuclear test in 1949, the U.S. Army veteran envisioned a weapons system armed not with munitions and other chemical explosives, but massive rods forged from heavy metals dropped from sub-orbital heights. Those “tungsten thunderbolts,” as the New York Times called them, would impact enemy strongholds below with the devastating velocity of a dino-exterminating impact, obliterating highly fortified targets — like, say, Iranian centrifuges or North Korean bunkers — without the mess of nuclear fallout.

Pournelle, whose years of experience in aerospace would fuel a career as a journalist and military science fiction writer, named his superweapon “Project Thor.” Others just called it “Rods From God.” In reality, weapons researchers refer to it as a “kinetic energy projectile”: a super-dense, super-fast projectile that, operating free of complex systems and volatile chemicals, destroys everything in its path.

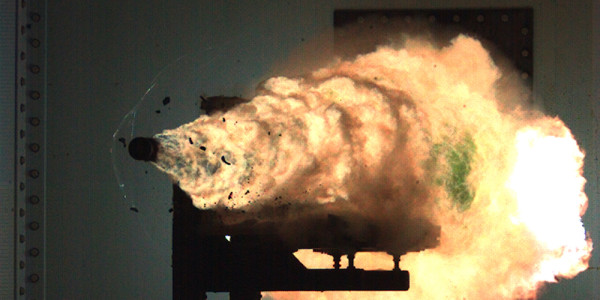

Photo via DARPA/Lawrence Livermore National Lab

A DARPA rendering depicts a supersonic conventional weapon as it emerges from its rocket nose. Not quite Jerry Pournelle’s ‘Rods From God,’ but just as terrifying.

The idea of kinetic weaponry — raining down inert projectiles on an enemy with deadly velocity — is far from a novel concept. The trebuchet was the backbone of successful sieges for hundreds of years, from ancient China to Hernan Cortes’ subjugation of the Aztecs; during and after World War II, airmen have occasionally deployed clusters of inert “Lazy Dog” bombs — metal cylinders traveling at terminal velocity — on the battlefields of Korea and Vietnam.

And gravity hasn’t always been necessary. For decades, militaries have used ultra-dense “kinetic energy penetrators,” also known as KEPs, specially designed shells often wrapped in an outer shell (a “sabot”) and fired at high velocity rather than dropped from the sky, to defeat defense armor. That’s the fundamental logic underpinning the U.S. Navy’s highly touted electromagnetic railgun, which can blast a 25-pound “hypervelocity projectile” with 32-megajoule muzzle energy through seven steel plates and obliterate whatever that armor is supposed to protect.

Whether dropped from the sky or fired from a cannon, the principle behind these weapons is the same: hitting the enemy with something very hard and very dense, moving very fast. And the kinetic energy projectile may become a staple of modern warfare sooner than you might think.

In 2013, the U.S. Air Force 846th Test Squadron and civilian researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory successfully test-fired a kinetic energy projectile, a tungsten-rich shell moving at 3,500 feet-per-second — more than three times faster than the speed of sound — on a specialized track at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico. More recently, the Pentagon has tested the Navy electromagnetic rail gun’s hypervelocity projectiles with the help of conventional U.S. Army howitzers; the Navy hopes the completed cannon will be able to launch shells at up to 4,500 mph, six times the speed of sound.

Explosives may be dazzling in their destructiveness, but there’s an elegant, almost Newtonian lethality to the kinetic energy projectile, explains Matt Weingart, a weapons program development manager at Lawrence Livermore.

“The classic way of delivering hurt against a target has been to pack a lot of chemical explosive into a container of some kind, a barrel or a cannonball or steel bomb,” Weingart told Task & Purpose in a phone interview. “The violence comes from the chemical explosive inside that bomb sending off a blast wave, followed by the fragments of the bomb case. But the difference with kinetic energy projectiles is that the warhead arrives at the target moving very, very fast — the energy is there to propel those fragments without the use of a chemical explosive to accelerate them. The more mass, the more violence.”

The concept of the hypersonic impact that defined Project Thor and its devastating potential hasn’t been lost on defense officials. Military researchers are continuing to explore battlefield applications that “take advantage of high terminal speeds to deliver much more energy onto a target than the chemical explosives they carry would deliver alone,” as Army Maj. Gen. William Hix put it at the Booz Allen Hamilton Direct Energy Summit in March.

“Think of it as a big shotgun shell,” Hix told the assembled crowd. “Not much can survive it. If you’re in a main battle tank, if you’re a crew member, you might survive but the vehicle will be non-mission capable, and everything below that level of protection will be dead. That’s what I am talking about.”

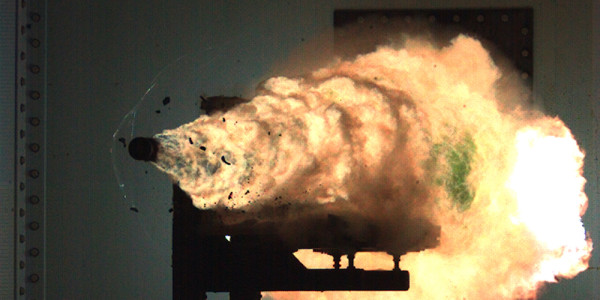

Photo via Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

An arena test at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s Site 300 used an aeroshell fashioned from commercial carbon composite panels. This experiment validated warhead performance prior to the sled test.

The KEP isn’t just appealing because of its elegance and relative cost-effectiveness (a super-dense tungsten warhead is relatively cheaper than conventional explosive munitions), but for its theoretical precision. The hypersonic shell is designed to defeat enemy armor and completely obliterate structures and equipment with extreme precision, whether it’s fired from ground artillery or deployed from an aerial — or orbital — platform. As Weingart explains, Hix’s vision is one of “raining down violence across a large area” — without, ostensibly, risking military personnel and hardware.

And the KEP’s upside isn’t just precision in targeting, but precision in the level of violence that the weapon actually deals out. Because the shell’s “yield” is essentially a function of velocity and density rather than explosive payload, confining the impact’s devastating effects to a specific area is simply a matter of physics. In theory, the KEP is “basic physics,” Weingart says, “but the implementation is really, really hard physics.”

“Using our high computing capabilities, we can exercise a high degree of control over those effects,” says Weingart. “We’ve got the most extraordinary computing power in the world, and we can take exquisite knowledge of physics and put it into very sophisticated computer codes and run vast number problems to predict how things are going to behave in terms of speed and energy.”

The KEP could offer a middle ground between the conventional precision GPS-guided munitions deployed by aircraft and high-yield, non-nuclear explosives like the GBU-43/B Massive Ordnance Air Blast (MOAB), or “mother of all bombs,” used against ISIS militants in Afghanistan in April. By adjusting the density of the KEP, military personnel could choose between defeating the armor on a single main battle tank and delivering violence wholesale (and simultaneously) across broad swaths of an operational area, without worrying about fallout.

“On the battlefield, you could do a straightforward calculation about whether the speed or amount of explosives are the most effective part of the warhead,” says Weingart. “Instead of putting explosives in, you just put in mass and heavy metals, regardless of delivery system or set of terminal conditions.”

“General Hix referred to it as a shotgun,” he added. “You can have a narrow or broad choke and spotlight a very small area with these effects if you’re trying to pinpoint a well-localized target without damaging the surrounding area.”

The Office of Naval Research (ONR)-sponsored Electromagnetic Railgun (EMRG) at terminal range located at Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division (NSWCDD). The EMRG launcher is a long-range weapon that fires projectiles using electricity instead of chemical propellants.

But what’s the main purpose of these kinetic energy projectiles, other than “raining down violence” with the shock and awe that only weapons like the “Mother of All Bombs” can inspire? For Pentagon planners, it could be to counter Russia’s tactical nuclear stockpile, according to Hix, warheads that could appear on future battlefields alongside conventional weapons thanks to ongoing miniaturization efforts, according to the DoD’s Russia New Generation Warfare Study.

Central to the weapons system’s tactical appeal isn’t its delivery mechanism, but the KEP warhead itself. While Weingart’s focus is on the KEP warhead rather than the firing system or combat context it might deploy in, he agrees with the potential application envisioned by Hix. “He is talking about the return of widespread violence to the battlefield, the fact we’ve seen the Russians do that in recent years by bombarding areas like Syria and Ukraine, the likes of which we haven’t really seen since the Korean War.”

The applications of the KEP are mainly theoretical for now, and we’re certainly decades away from a floating Thor’s hammer circling the planet. But if kinetic energy projectiles do find efficient applications in warfare, it’s possible they could find new delivery systems for battlefield destruction — with potentially devastating effects that might eclipse the MOAB as the most violent non-nuclear weapon in the Pentagon’s arsenal.