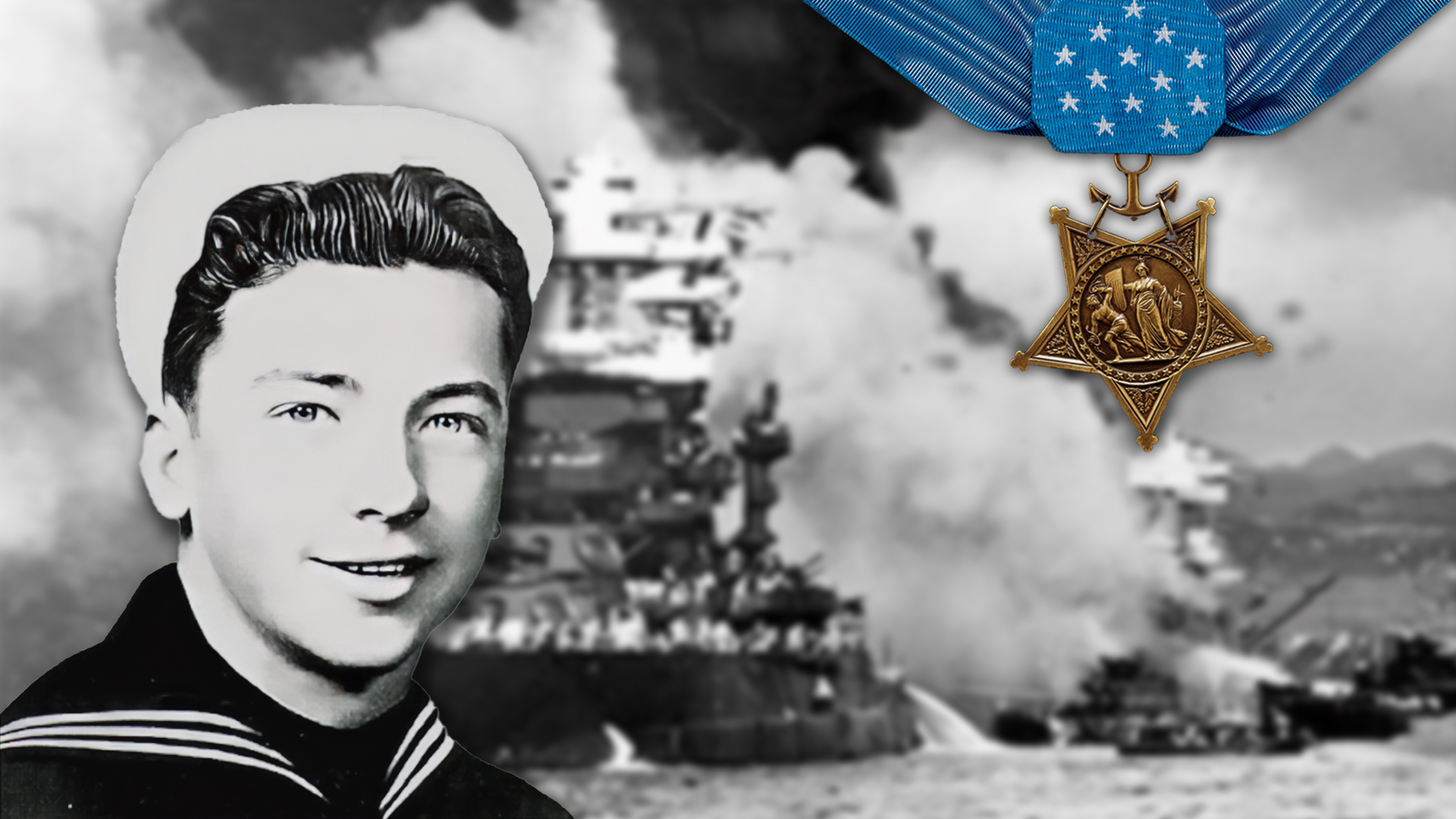

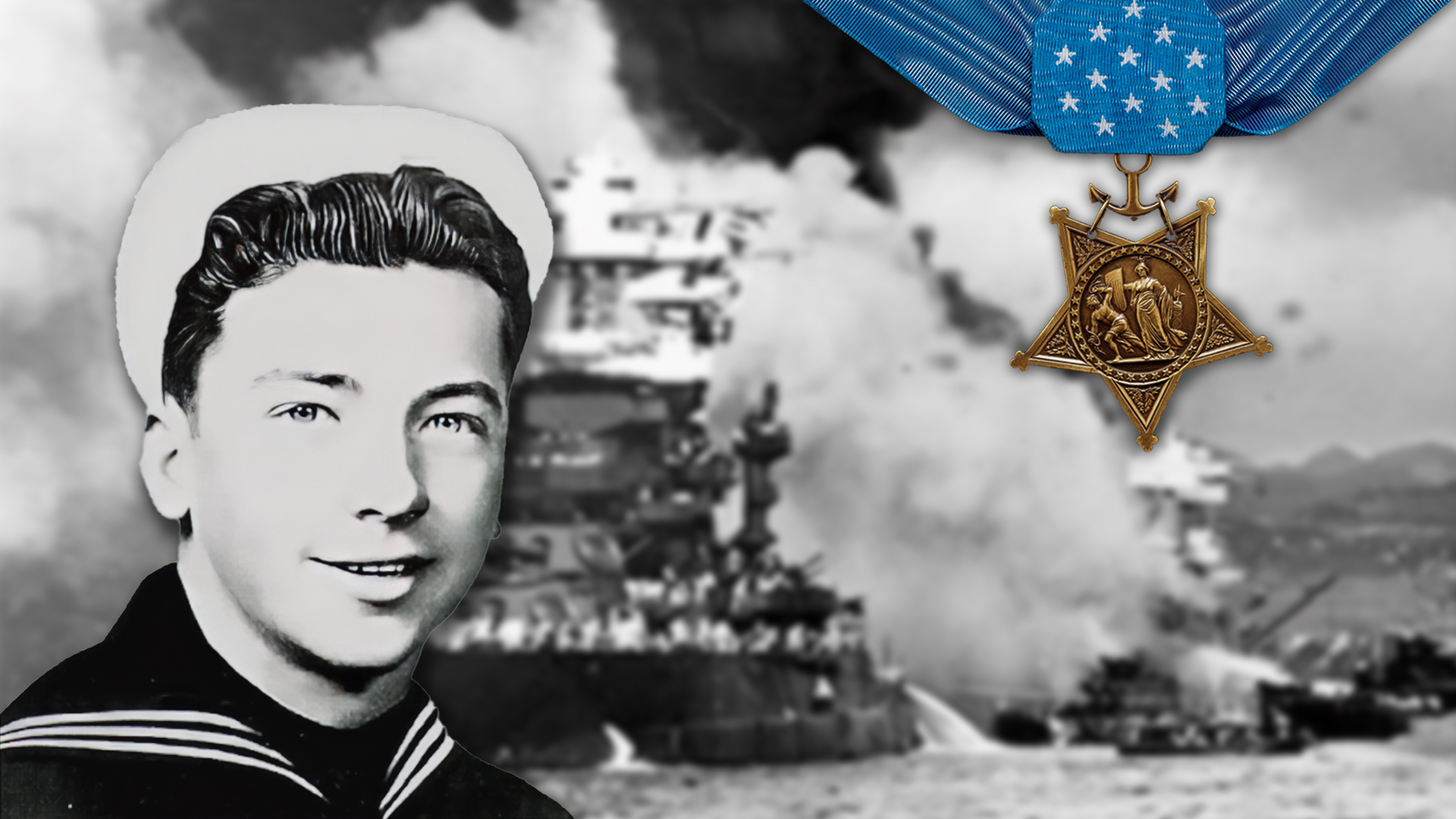

One of 16 sailors awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions during the attack on Pearl Harbor will be interred in Arlington National Cemetery this month, nearly 82 years after he died saving his fellow sailors.

Navy Seaman 1st Class James R. Ward, of Springfield, Ohio, was killed on Dec. 7, 1941, when he stayed aboard the sinking USS Oklahoma to help fellow crewmen escape. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 1942, one of 16 awarded for actions during the attack that drew the U.S. into World War II.

But Ward’s remains were only identified by DNA analysis in 2021.

Fourteen Navy sailors at Pearl Harbor were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions during the attack. Another sailor, Chief Aviation Ordnanceman John Finn, was awarded the Medal for keeping up a barrage of anti-aircraft fire at attacking Japanese planes from his post at Kaneohe Bay, on the opposite side of Oahu from the harbor. Marine 1st Lt. George H Cannon was awarded the Medal for leading the defense of Naval Air Station Midway, which was also attacked that morning. Ten of the sailors at Pearl Harbor including Ward, along with Cannon at Midway, died during the attacks.

Ward’s actions were attested to by his fellow sailors on the USS Oklahoma but his remains were among 619 who were never positively identified in the years that followed. In 2015, the Pentagon launched the USS Oklahoma Project to identify those sailors, whose remains had been interred in the Cemetery of the Pacific since soon after the war.

To identify the remains, the project sought DNA from relatives, including Richard Ward Hanna, 67, Ward’s nephew and namesake. Hanna’s mother was Ward’s sister. Hanna knew about the program to identify sailors from Pearl Harbor and was happy to help lay his uncle to rest and get a “sense of closure.” Hanna told Task & Purpose that he and a few other distant relatives gave DNA samples to the Navy and experts were able to identify his uncle with a large leg bone and the bottom of a jaw.

Ward was 20 years old and had been in the Navy for only six months when the attack on Pearl Harbor took place.

Hanna said he’s not sure how his uncle would feel about receiving the Medal of Honor. He thinks Ward would’ve said something along the lines of, “I’m no more a hero than anyone else was on that day.”

Hanna is flying in from Gainesville, Florida to attend the Dec. 21 burial at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. He’s also going to meet distant relatives he would’ve never connected with otherwise.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news and culture in your inbox daily.

Hanna said his mother didn’t speak much about her brother’s death or being awarded the nation’s highest military honor. Hanna said it was because they were from a different generation that was less open. The only information Hanna did know was that his uncle was a good baseball player.

“It was an easy decision,” Hanna said about doing a formal ceremony. “I took into account how my mother would feel about that, how my grandparents, his parents, would feel about that. I think they’d be very proud.”

A friend of Ward’s who grew up with him in his hometown is also planning to attend. Ward’s legacy, Hanna said, is “a big deal in Springfield, Ohio.”

The USS Oklahoma Project

Between December 1941 and June 1944, the Navy recovered and interred the USS Oklahoma crew’s remains, including Ward’s, at the Halawa and Nu’uanu Cemeteries in Hawaii.

In September 1947, the American Graves Registration Service disinterred the remains and transferred them to the Central Identification Laboratory at Schofield Barracks. By the end of the 1940’s identification efforts, there were 619 unknown remains associated with the attack on Pearl Harbor, according to Dr. Aelwen Wetherby, a Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency historian.

They buried those unidentified remains at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, often called “the Punchbowl,” in Honolulu, Hawaii, and marked them as non-recoverable.

In 2015, the DPAA launched the USS Oklahoma Project, to exhume the unknown sailors for modern analysis. Using dental and anthropological analysis, they were able to identify Ward along with 362 Sailors and Marines. The DPAA officially marked Ward as identified on Aug. 19, 2021.

Ward was assigned to the USS Oklahoma at Ford Island, Pearl Harbor when the base was attacked by Japanese bombers. The battleship sustained multiple torpedo hits and capsized, killing 429 of the 1,353 crew members, 415 of which were Navy sailors with 14 Marines, according to DPAA.

Before the ship capsized and sailors were ordered to abandon ship, Ward stayed behind in a turret and held a flashlight so other members of the crew could see to escape.

He never made it out.

In addition to his posthumous award, a destroyer escort was commissioned in 1943 and named in his honor as the USS J. Richard Ward. The vessel sailed through the end of World War II.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor killed nearly 2,400 Americans, which included both military personnel and civilians across Oahu. More than 1,100 were wounded. Twenty-one ships were sunk or significantly damaged along with 188 U.S. aircraft destroyed and 159 damaged. Additional casualties were recorded from attacks on Wake Island and Midway Island where the merchant marine vessel SS Cynthia Olson lost 33 merchant marine crew and two Army passengers.

DPAA has also identified 15 sailors from the USS West Virginia from the 106 crew members killed during the attack and five from the USS California which lost 102 crew members.

UPDATE: 12/8/2023; This article has been updated with more recent numbers on the DPAA’s identification of crew members from the USS West Virginia and USS California.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Marine Infantry veteran says enlisted shouldn’t become officers — mayhem ensues

- Father loses 80 pounds, joins Air Force alongside his 2 sons

- Opinion: Veterans won’t help the recruiting crisis until our issues are addressed

- Navy fires head of Amphibious Squadron 5 for ‘loss of confidence’

- How much do CIA case officers get paid? A look at life as a spook