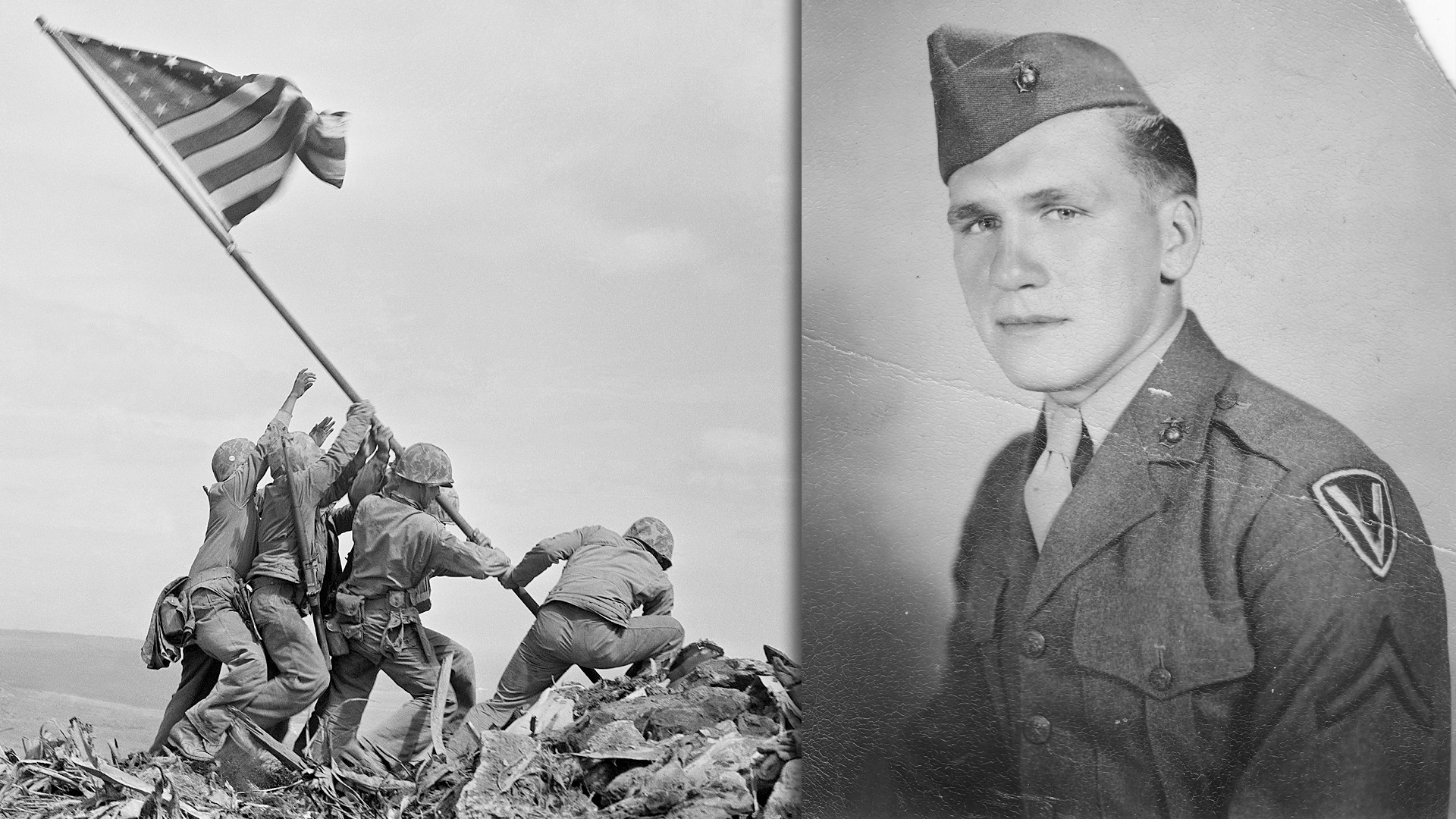

It is one of the most widely reproduced photographs in human history, and perhaps one of the most iconic images of World War II. It has inspired every form of media from major films like “The Sands of Iwo Jima” to physical monuments of marble and granite. It is an image which has, for many, underscored countless struggles, from the effort to rebuild Ground Zero in the wake of 9-11 to the LGBTQ movement, organized labor and even anti-war protests.

By far this image, officially titled “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima,” has inspired many emotions, from endurance to triumph, from solemn struggle to national pride. Few in the West haven’t seen the grainy black and white celluloid image of six young men in battered fatigues, battle rifles slung over their exhausted shoulders, stabbing a metal rod into the rocky, shell-cratered summit of Mount Suribachi and raising a crisp red, white and blue American flag over a battle-scarred landscape. Yet, what many do not know is that this image holds a secret only a handful of men and their closest friends and family members ever knew, until very recently when some stunning revelations were made.

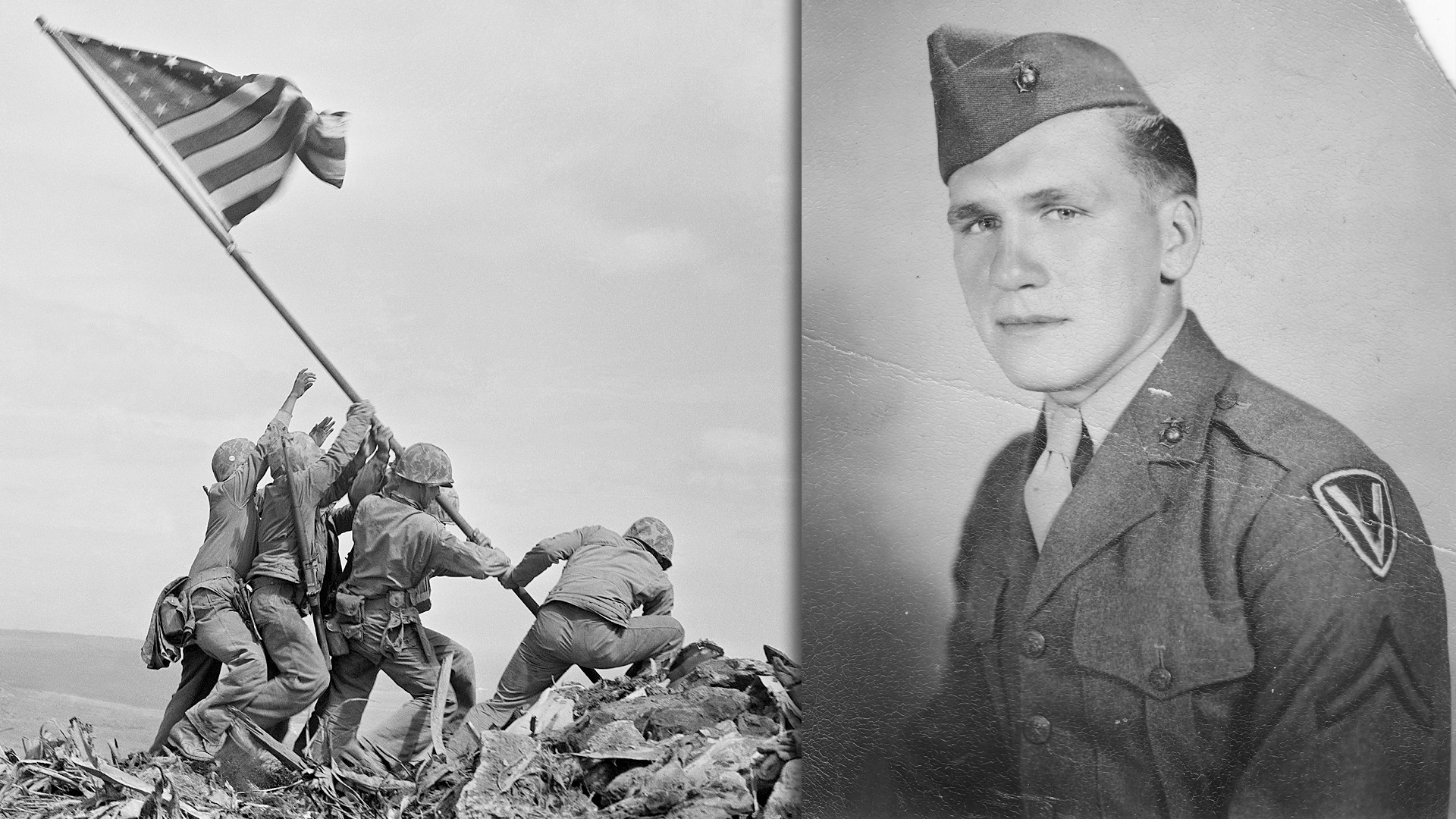

In the rose garden of Hollywood Forever Cemetery stands a humble marble bench dedicated to U.S. Marine Cpl. Harold Henry Schultz. It reveals he was a recipient of the Purple Heart Medal during his service in World War II and honors him as a loving husband and father. What the bench doesn’t tell is how Schultz was one of the six Marines who participated in that historic flag-raising, frozen in time by Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal’s unforgettable picture. That’s because Schultz kept his participation in the Iwo Jima flag-raising photo a personal secret all his life. While he’d once mentioned it in passing to his stepdaughter, Dezreen MacDowell, it was never something he cared much to mention or seek attention for.

On the morning of February 23, 1945, Pfc. Schultz was a Marine mortarman, filling in as a rifleman with 3rd Platoon, Easy Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Division. It was the fourth day of fighting in the Battle of Iwo Jima when 3rd platoon leader 1st Lt. Harold George Schrier received the battalion’s American flag and orders to raise it on the summit of Mt. Suribachi and set up an observation post. Schrier, a battle-hardened former Marine Raider and executive-officer of Easy Company, commanded Schultz and 42 other men on this mission, including a Marine combat photographer, Staff Sgt. Lou Lowery. As the team climbed up the bunker and cave-ridden volcano, Schrier and his men met little resistance. With the mountain-top secure, Schrier’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. Chandler Johnson, ordered Schrier to raise the 54-by-28-inch flag.

Lowery snapped several photographs of the Marines raising the first American flag on Mt. Suribachi. The moment would be cut short, however, when Japanese soldiers launched a surprise attack with small-arms fire and hand grenades. Lowery’s camera broke as he sought cover but he managed to salvage his photographs. The first flag raising passed with little excitement as the flag was too small to be seen by the troops below or from the invasion beachheads. While Schultz and his team maintained security at the top of the mountain, Johnson sent up his runner, Pfc. Rene Gagnon, with a larger, 96-by-56-inch flag and orders to link up with Schrier, deliver the flag along with spare radio batteries. He would also retrieve and return the original flag raised atop Suribachi.

On his way up, Gagnon was joined by another Marine combat photographer, Pvt. Robert Campbell, along with videographer Sgt. Bill Genaust. Joining the hastily assembled team was Associated Press Photographer Joe Rosenthal. When the flag reached Schrier, he made certain the new flag went up just as the old flag went down. Shultz, who had been providing security, was called out to help raise the flag. He took up a position in front of Pfc. Ira Hayes and helped raise the flag along with four other Marines. As the new flag was raised Rosenthal captured his soon-to-be famous photograph, meanwhile Campbell captured both flags in their upward and downward journeys. Within hours, Rosenthal’s legendary photograph was en route to being published in thousands of periodicals along with news articles of the unfolding battle raging on Iwo Jima. The image of six Marines hoisting up an American flag rippled through the American war effort as workers, volunteers, soldiers, airmen, sailors and their fellow Marines observed the results of their tremendous sacrifice manifested in the raising of their nation’s flag over enemy territory in what was one of the bloodiest confrontations of the entire war.

However, as the world embraced the photo, hoping for the eventual victory it would come to represent, the Battle of Iwo Jima raged on for weeks, inflicting a heavy toll on the men involved. The Marines who’d participated in both flag raisings were no exception. Three Marines in Rosenthal’s photograph, Sgt. Michael Strank, Cpl. Harlon Block and Pfc. Franklin Sousley would be killed in action before the fighting on the island was over. Johnson and Genaust were also killed on Iwo Jima along with what would total another 6,800 other Americans. The battle ended in an American victory, albeit a costly one. On March 26th, nearly 20,000 Japanese, in addition to the aforementioned 6,800 American service members lay dead.

On March 13, Schultz was wounded in action, taking shrapnel to the abdomen and right thigh. Although he had been one of the six men to hoist the second American flag on Iwo Jima, he, along with another surviving flag raiser, Pfc. Harold Keller had not been properly identified as one of the second flag raisers. Instead, for reasons lost in the frantic efforts of war, Pfc. Ira Hayes, Pfc. Gagnon and Navy Hospital Corpsman Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class John Bradley were identified as the flag raisers for a publicity campaign to raise money through the sale of war bonds called The Seventh War Loan Drive. This war bond drive would produce 3.5 million posters featuring Rosenthal’s photograph.

The three would reluctantly become celebrities, even posing for the Marine Corps War Memorial made in the likeness of the second flag-raising photo in Washington D.C. to honor the Marine Corps’ war dead in 1954. Schultz himself would spend his time after the flag-raising in a naval hospital, recovering. While he no doubt saw the war bond drives, the posters, newsreels and interviews delivered to service members and civilians on an almost daily basis, he never made any mention of the role he played. Eventually, he would leave the Marine Corps and return to civilian life in California. While the war would forever change him in some ways, he retained his humble mid-western views.

Dezreen MacDowell, the last surviving relative of Schultz, only heard her step-father mention something about the photograph once in passing over dinner.

“It was sometime in the 90s before Harold died,” recalls MacDowell. “Harold said he was one of the flag raisers on Iwo Jima, and I told him he was a hero — to which he said, ‘No, I was a Marine.’”

By 2016, after receiving a tip from amateur historians Eric Krelle and Stephen Foley, the Marine Corps initiated its own investigation into the identities of the flag raisers by scouring through the pictures taken by Lowery, Campbell, Rosenthal photos as well as Genaust’s footage from that fateful February day. The investigation would conclude in 2016 with the announcement that Pfc. Harold Schultz was actually the Marine in the photograph, not Navy Corpsman John Bradley.

Rather than correcting the Marine Corps’ mistake, Schultz opted to keep his experience of the flag-raising mostly to himself, never publicly speaking of the event. In fact, he would go on to live a remarkably anonymous and solitary life.

Schultz died of a heart attack on May 16, 1995, in Los Angeles at the age of 70. He was born in Detroit, Michigan on January 28, 1925, and enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve on Dec. 23, 1943, training in Camp Pendleton, California, and Camp Tarawa, Hawaii prior to his participation in the invasion of Iwo Jima.

“He had a Midwestern way about him, where he never talked too much and never complained about anything,” recalls MacDowell. “He was the laconic type and definitely was a ‘character’ in every sense of the term.”

After recovering from his war wounds at a naval hospital in Hawaii, Schultz was eventually discharged from the Marine Corps. He settled down in the Pico-Union district of Los Angeles and took up a job sorting mail for the United States Post Office in 1946, and worked at the main post office in downtown Los Angeles, called Terminal Annex, between Chinatown and Olvera Street until his retirement in 1981. He worked the night shift for his entire career at the Post Office.

“Harold never drove or owned a car during the years I knew him,” said MacDowell. “He was a great believer in public transportation and took the bus to work.”

MacDowell describes her relationship with Schultz as them being very “simpatico.” MacDowell was the daughter of Rita Reyes Schultz, who was Schultz’s next-door neighbor for several decades.

“Harold lost the love of his life, an Armenian girl named Mary, to a brain tumor,” recalls MacDowell. “Sometime in the 1970s I saw him reading an old letter she wrote to him and he had tears in his eyes. Mary wrote to him as ‘her handsome blonde.’” Though they were in a committed relationship for many years, Schultz and Mary never married.

However, later on in life, Schultz would marry his neighbor Rita when they were both in their 60s. During his lifetime, Schultz had a love for animals and fostered stray cats in his neighborhood. He donated money to animal rescue societies in Los Angeles and organizations that helped Native American children.

One of Schultz’s favorite pastimes was going to the horse races at Hollywood Park racetrack and at Santa Anita Park. He would sometimes bring MacDowell along with him. When further describing Schultz’s personality, MacDowell says her picture of her late stepfather is of “him wearing a monk’s habit, with a racing card in his hands.”

“He was very quiet about his military service,” recalls MacDowell. “One of the bits and pieces I remember is while we were watching the film Patton sometime in the 1980s, Harold said he saw his best friend get blown up on Iwo Jima.”

While MacDowell recalls he sometimes exhibited symptoms associated with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, “back then it was not popular to go to a psychologist and talk about your feelings,” said MacDowell. “Harold was the kind of person who compartmentalized his trauma.”

Yet for all his experiences in one of the deadliest conflicts in human history, Herald retained his sense of humanity.

“Herald was a progressive in his beliefs. He was pro animals, pro-civil rights, pro Native American rights and pro-gay rights. He was an interesting man in every sense of the word,” Dezreen said.

The way MacDowell describes Schultz’s life and personality offers some insight into Schultz’s keeping his participation in Rosenthal’s flag-raising photo a secret. Perhaps we’ll never know. Eventually, it came to be known that Herald Keller, not Rene Gagnon, was one of the second flag raisers. Keller had been misidentified as Gagnon all these years.

Harold Schultz, much like other veterans of the war he’d fought in, would keep his secrets long after the guns had fallen silent. In fact, for nearly all who knew him, he kept his secret even unto his death. Unlike the image which would forever enshrine him in history, he preferred to maintain a low profile, recognizing his service for exactly what it was: service. Perhaps, as the dust from these most recent wars settles, we’ll discover the unknown heroes, both living and dead, who’d chosen to remain humble and in obscurity rather than seeking attention or the limelight. Only time will tell. For now, however, we can only put our noses to the documents, the records, the old social media posts on everything from Myspace to Facebook, from old war letters to long-forgotten polaroids and see what other hidden stories there are to uncover.

What’s hot on Task & Purpose

- A Marine sued the Navy over how it handles ‘bad paper’ discharges and won

- Army 3-star general suspended amid investigation into toxic climate and racist comments

- The best gear under $25 to make life in the field suck less, according to soldiers

- How a rivalry between two WWII vets led to the world’s smallest flyable airplanes

- Air Force Reserve major helps to subdue unruly passenger aboard American Airlines flight

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.