Early next month a decorated Special Forces colonel who disobeyed orders to save the lives of his men during a fierce battle in Vietnam in 1965 will receive the Medal of Honor at a ceremony in the White House. The award recognizes Col. Paris Davis’ courage under fire that day 58 years ago, but it is also a testament to the dedication of a team of veterans who took on the Pentagon bureaucracy to get Davis’ nomination package approved more than half a century after it was inexplicably lost in the system.

“We got pushback every single step of the way,” said Neil Thorne, an Army veteran and one of the key volunteers who helped resurrect the push for Davis’ Medal of Honor over the past nine years.

“We could have given up at any time in that nine years and it would have gone nowhere,” he said. “So part of it was persistence and part of it was just getting people to understand what happened here.”

What happened was a larger-than-life story of unbelievable heroism, inconceivable negligence, and dogged determination — and that’s just the beginning.

Building a beehive in a hornet’s nest

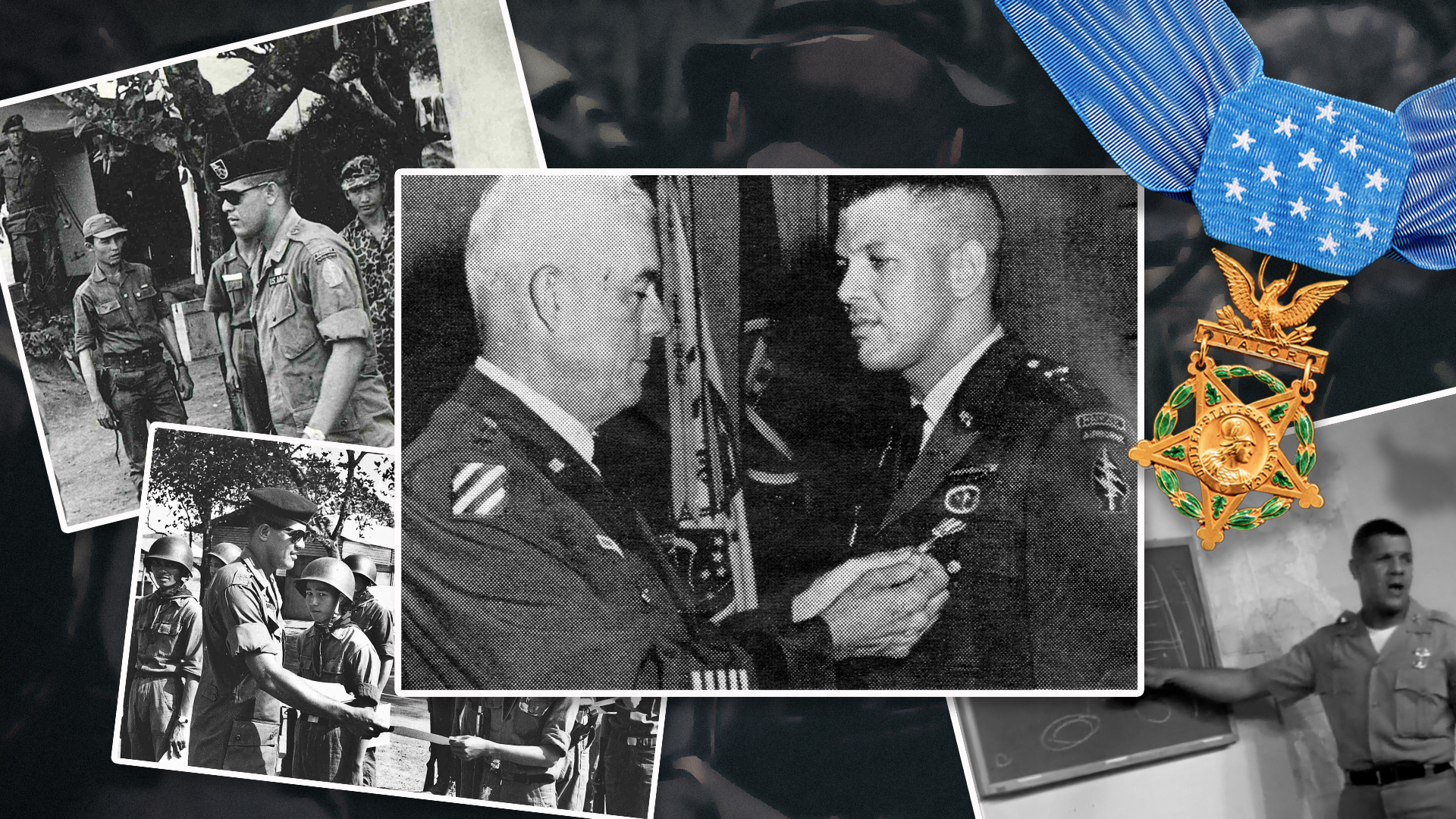

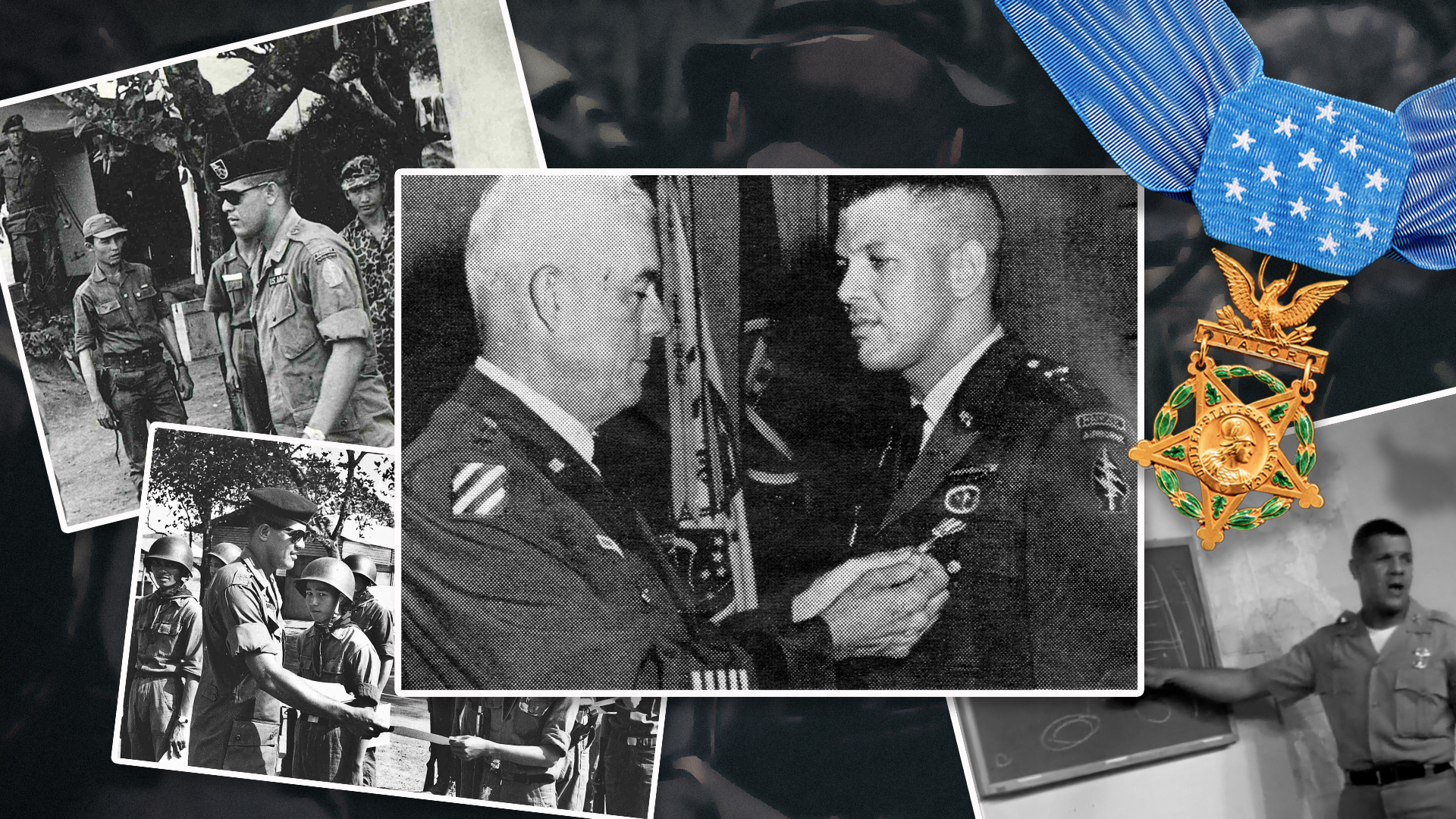

In June 1965, then-Capt. Paris Davis was one of the first Black Special Forces officers in U.S. history and, according to Thorne, he was universally beloved by the men under his command.

“Every single person who I have spoken to, probably about 12 people, who served under Col. Davis over the years use the same phrase, ‘he was the best commander I ever had,’” Thorne said.

Just a month earlier, in May 1965, Davis was awarded a Soldier’s Medal for risking his own life to pull a comrade out of an overturned fuel truck before it exploded. But while the men under him loved Davis, a few of his fellow Special Forces officers held a different opinion.

“You can hear the animosity in the tone … it does not match with what the people who served under him say,” said Thorne, who has spoken with several of those officers. “It was more animosity for folks loving him and his success.”

That animosity may have been amplified when Davis volunteered to take on a near-impossible mission: help push back North Vietnamese and Viet Cong control of Binh Dinh Province, located on the country’s south central coast. To do that, Davis was to build a new Special Forces camp at a village called Bong Son while also training a volunteer unit of Regional Forces /Popular Forces, commonly referred to as Ruff Puffs. Ron Deis, a junior member of Davis’ Special Forces A-Team in Bong Son, said the task was similar to building a beehive in a hornet’s nest

“It was a hotbed … when we went on an operation, we always were outgunned, we always got into situations that were very precarious,” Deis said.

‘The move saved his men from being overrun’

On the night of June 17, 1965, Davis led three Green Berets and a company of about 100 Ruff Puffs in a raid against North Vietnamese forces northeast of Bong Son. That night and into the next morning, Davis’ troops captured four enemy soldiers who revealed a nearby force of 200-300 well-trained, well-armed North Vietnamese troops. The information was confirmed at around 5:30 a.m. on June 18 by Deis, who was serving as a spotter aboard a tiny L-19 Bird Dog propeller plane circling overhead. Not long after that, enemy troops detected Davis’ company and the battle commenced.

“Davis charged forward, opening fire with his M-16 and killing five NVA soldiers,” read Davis’ Medal of Honor narrative. “So intense was the fire coming from the enemy that the spotter aircraft with Deis on board was damaged and forced to return to the Bong Son camp.”

Despite being outnumbered, Davis rallied his troops and attacked what he suspected to be the enemy command building.

“He moved to a window and threw a grenade inside, then burst into the house, killing 10 NVA with his rifle and rifle butt,” read the narrative. “In leading the assault, Davis killed at least 10 more enemy fighters. Davis received a wound in the right forearm during the firefight.”

The Green Beret then went on with a small group to “engage four NVA soldiers in hand-to-hand combat and with his rifle butt,” the narrative said. But by now the element of surprise had been lost, so the captain split his troops and began moving them back into better positions. Several bugle calls from the enemy troops signaled a counterattack. Davis killed two more enemy soldiers and suffered his fingertip being shot off, according to the narrative.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

By around 7:45 that morning, Davis and the survivors of his force moved toward a hill where the North Vietnamese left behind several dozen foxholes. But Davis’ troops were not in great shape: all four Green Berets had been wounded several times and while the Ruff Puffs were motivated to fight, their youth and inexperience made them prone to break under sustained enemy pressure.

“These young men, they did what was asked of them and under enemy fire they probably were not as organized [as a more seasoned unit] but it was not for lack of wanting to do the right thing,” Deis said.

To make matters worse, Davis’ team sergeant, Master Sgt. Billy Waugh had been shot three times and pinned down in a buffalo wallow, a sort of depression that holds rainwater. Meanwhile Davis’ demolitions specialist, Staff Sgt. David Morgan had been knocked out by an exploding mortar and was taking sniper fire as he regained consciousness, and the team medic, Spc. 4 Robert Brown Jr., was unaccounted for, though Davis did not know it yet.

The captain spotted the enemy sniper targeting Morgan from a camouflaged foxhole and shot him with his M-16, the narrative said. By around 8:30 that morning, Davis regained communication with his split force and over the next two hours, he used a PRC-10 radio to call in artillery and airstrikes against enemy positions.

“This move saved his men from being overrun by the vastly superior enemy force,” the narrative reads.

‘That was quite the statement’

But the fight was far from over: Davis realized that Brown was unaccounted for, Waugh could not move because of his injuries, and Davis himself was pinned down. Around noon, the captain took matters into his own hands: calling an artillery strike within 30 meters of his position to carve a route so he could rescue Waugh. For context, the Army considers any artillery strike within 500 meters of a friendly position to be “danger close.” Davis and a fellow Green Beret, Sergeant 1st Class John Reinburg, rushed through open ground to pick up Waugh and pull him out of danger.

Billy Waugh is a legend in the history of Army special operations. Besides serving in the Korean War and later as a Green Beret in Vietnam where he conducted the first military freefall high altitude, low opening (HALO) jump in a combat zone, Waugh also worked for the CIA in Libya, spied on terrorist leaders in Sudan, and at the age of 71 he helped topple the Taliban during the opening salvos of Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan in 2001.

But sometimes even legends need rescuing, and Waugh’s rescuer in Bong San was Capt. Paris Davis. The captain carried the wounded Waugh fireman-style back up the hill, where a helicopter had landed carrying a wounded door gunner and Davis’ commander, Maj. Billy Cole. The major told Davis to leave with the wounded and said he would relieve him, but the captain refused.

“Sir, please do not do that to me. I’m not hurt that bad,” Davis said, according to the narrative. “I’ve got to get my men out of this predicament. We have another strike on the way. I refuse to go.”

“You’ve got it, Dave,” Cole replied. “Good luck and God bless you.”

Though Reinburg was wounded in the chest shortly after Cole departed, Davis kept guiding in artillery and airstrikes, preventing his troops from being annihilated. The captain then crawled more than 150 yards to drag Brown back to friendly territory, though Davis was wounded by grenade fragments. After almost 19 hours of nearly continuous combat, the enemy finally retreated as friendly reinforcements arrived.

Davis’ men already admired him for being extremely brave, Deis said, but it was clear that something extraordinary had just happened.

“Sgt. Morgan said to me, ‘I think Capt. Davis deserves the Medal of Honor for what he did out there.’ That struck a note with me that I never forgot,” said Deis. “Sgt. Morgan had a lot of combat experience, so for someone with his experience to say that … that was quite a statement for him to make.”

Unfortunately for Davis, it would be more than half a century before he received what he deserved.

‘Everybody was waiting for something that’s in a garbage bin’

Maj. Billy Cole, Davis’ commanding officer, submitted the captain’s nomination for the Medal of Honor shortly after the battle in July 1965. In December, Davis was awarded the Silver Star “as an interim award while the Medal of Honor packet was assumed to be in-process,” according to documents from Davis’ resubmission package.

The years passed and by 1969 there was still no word on the medal. The Army could not find the nomination packet, despite Maj. Cole formally submitting it at the Special Forces headquarters in Nha Trang. Thorne said this is the first proven case of a lost Medal of Honor nomination packet in U.S. history.

“Everybody was waiting for something that’s in a garbage bin,” said Thorne, who estimated he has helped recover 30 to 50 missing, lost, or downgraded military award nominations over the years. “You just don’t see a Medal of Honor packet get lost … it’s a big deal. It got trashed.”

Medal of Honor nominations also require substantial paperwork such as eyewitness statements, a unit report of the action, maps, and other documents, Thorne explained. It still baffles Deis that the Army could lose such a packet, considering the sanctity of the Medal of Honor.

“I could not believe that someone would risk their life to the level that he did and not have everybody in the Army at that time respect that heroism and not at least take that recommendation seriously,” he said. “It befuddles me, it just overwhelms me to think that someone could possibly lose a recommendation for the Medal of Honor.”

In the years since then, some volunteers suspected that racism played a role in the nomination being lost. Thorne said that would have fit with the era, just a year after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed.

“There’s nothing that overtly spells out racism, but look at the times,” he said. “Given that time, and with him being one of the first Black Special Forces officers … everything points to there being something against him.”

An official Army inquiry in 1969 deemed that the nomination had indeed been lost or destroyed and that a new one was needed. However, Thorne found no evidence that a new one was submitted.

“Twice Davis’s nomination has had the opportunity for official recognition and twice that nomination has been lost, or through inadvertence not acted upon,” read the revived package decades later.

‘It only takes one bad egg’

Years passed, and in 1981 Billy Waugh attempted to resurrect the effort to get his old captain the Medal of Honor, Thorne said. After that effort failed, thirty more years went by before a serious group of volunteers gathered to get Davis, who retired from the Army in 1985 at the rank of colonel, the recognition he deserved. Thorne became involved in 2014, and he leveraged his expertise in the military award process to put together a thorough resubmission of the package.

“They had not pulled any of the records so we started doing that,” Thorne said. “During that time we were hunting for eyewitnesses, anybody that might have been there: chopper pilots, forward air controllers, FAC pilots.”

Part of the trouble was that some of the eyewitnesses had died in the intervening years either due to old age or enemy fire. For example, Staff Sgt. Morgan was killed in combat later in 1965 and Spc. 4 Brown never recovered from the wounds he suffered in Bong Son that day. But between the statements and documents filed in support of Davis’ case over the years and a 1969 special episode of the Phil Donahue Show where Davis and other soldiers were interviewed about the battle, they had enough evidence to resubmit the nomination in 2016. But no matter how thorough a nomination package may be, the team found the military bureaucracy moves at its own pace.

“Any time you’re dealing with any one of these steps, whether it be the Army’s Awards and Decorations Branch, the Secretary of the Army level, or the Secretary of Defense level, you’re also dealing with people and personalities,” said Thorne.

For example, Thorne said that one point the package was held up by the commander of Fort Knox who, despite the package having evidence from the National Archives, did not believe there was enough proof that Col. Davis had been nominated for the Medal of Honor in 1965.

“I sent a very, I’ll say ‘terse’ email, because I was pretty much fed up at that point, and it just so happened to land on the desk of the new commander” at Fort Knox, Thorne recalled. “He took one look at it and said ‘this is going forward.’ That was our first break.”

The process continued in fits and starts through each level of the Army and the Secretary of Defense. Each step takes months just for the relevant party to review the package, and at each step, the package may get shot down, either because of minor typos or out of some kind of office habit.

“Anyone can say no the first time,” Thorne said. “I have no proof of this but I always wonder if that first kick-out is so they can say they did their due diligence.”

Thorne does not know where the institutional bias to say ‘no’ comes from, but he pointed out that there are plenty of helpful people in the process too.

“It’s the good people who help move it forward, who can look at it with open eyes and not be ready to say ‘no’ right off the bat. And we’ve encountered plenty of those too,” he said. “But it only takes one bad egg to cost you months or years.”

For example, the package was held up for three years at one point by a member of the Secretary of Defense’s office of Manpower and Reserve Affairs. Thorne said he thinks the member “was determined to say no just because he said no the first time.”

When pushback happens, it often takes more than just an immaculate nomination package to push through the bureaucracy: it takes connections to people who can speed up the process.

‘I’m not smart, but I’m relentless’

In 2015, Jim Moriarty, a lawyer who served with the Marine Corps in Vietnam, joined the project. A former director of the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, Moriarty said he had connections with several high-level military leaders including then-Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis, then-Secretary of the Navy Richard Spencer, and then-White House Chief of Staff John Kelly.

“I’m surrounded by people who have all sorts of stroke and I’m hitting on everybody I know: ‘we need to go award Paris Davis the Medal of Honor,’” Moriarty said.

Moriarty did not just know people with pull, he was also willing to pester them to get their support for Davis’ case.

“I’m not smart, but I’m relentless,” he said.

Moriarty’s pull and Thorne’s meticulous documentation helped keep the package moving through the bureaucracy, but by 2020 it was stuck again within the Office of the Secretary of Defense. Davis’ team was worried that the colonel would pass away from old age before the upgrade process was complete, but salvation came in the form of the new acting Secretary of Defense Christopher Miller, a veteran of the 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), the same unit Davis was assigned to when he was a captain at Bong Son.

The 5th SFG(A) was also the unit Moriarty’s son Jimmy belonged to when he was killed by a gate guard in Jordan in 2016. Moriarty eventually got Miller’s attention through a chain of connections and contacts. It paid off: Moriarty said Miller played a key role in not only his son receiving the Silver Star but also Davis receiving the Medal of Honor, though it took until earlier this month for it to finally become official.

“As I anticipate receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor, I am so very grateful for my family and friends within the military and elsewhere who kept alive the story of A-team, A-321 at Camp Bong Son,” Davis said in a statement when the news broke on Feb. 13 that he would receive the medal. “I think often of those fateful 19 hours on June 18, 1965 and what our team did to make sure we left no man behind on that battlefield.”

When asked if his perception of the medal has changed over the years, Deis said he thinks it means more to him now than it did in the years directly after the battle.

“When you’re young like I was and you witness those things [in war], it puts a hard edge on you. Maybe that’s a self-defense mechanism,” he said. “But as you age, that hard edge breaks down and it just makes you more emotional. That has been my experience so that every time I see the Medal of Honor being awarded it makes me cry … because I know what it takes to get that medal.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Why the Air Force’s best ‘secret weapon’ has nothing to do with airplanes

- Ohio National Guard leader filmed shoving a journalist

- Why being a Marine is more of a bonus than actual money

- Why is the US military suddenly shooting down every UFO in the sky?

- No, an F-22 isn’t rocking an aerial victory marking for that Chinese spy balloon — yet

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here.