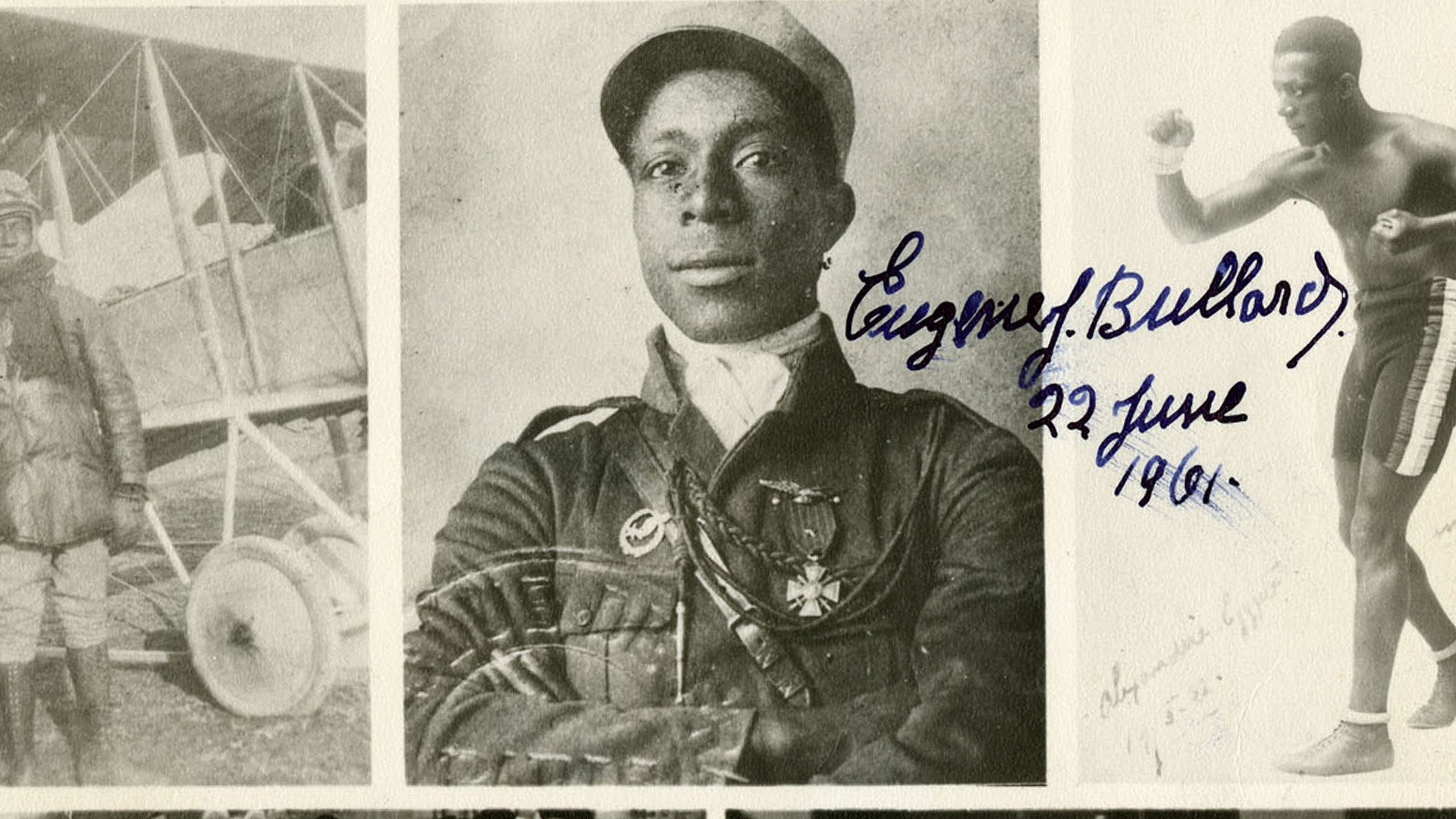

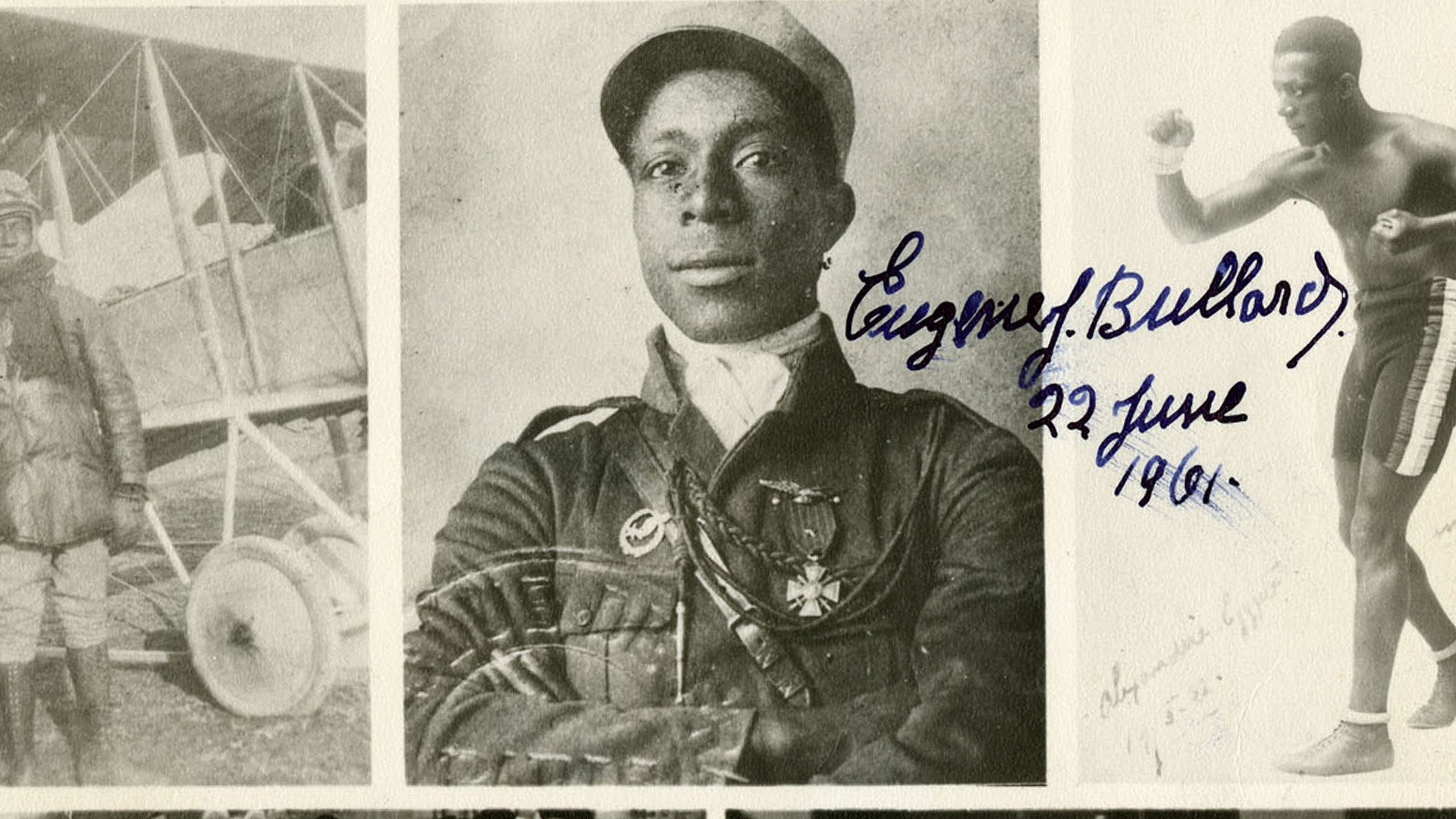

If there were ever a candidate for a real-life ‘most interesting man in the world,’ it would be Eugene Jacques Bullard. The son of a former slave, Bullard ran away from home in Georgia and moved to Europe at an age before most learn how to drive. He went on to fight in two world wars, brushed elbows with some of the most famous artists of the early twentieth century; become a French national hero; and, on a bet, become one of the world’s first black combat pilots.

But despite Bullard’s many accomplishments, his story remains little known in the United States. It’s unclear exactly why, but the racism he encountered in his home country throughout his life may have played a role. Born in Columbus, Georgia, on October 9, 1895, Bullard came face-to-face with that racism early on when his father was nearly killed by a lynch mob, according to the Public Broadcasting Service. The Bullard home itself was a troubled one, according to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, so in 1906, the 11-year-old Eugene ran away from home, joined a group of gypsies and worked as a stable boy before eventually stowing away aboard a freighter bound for Scotland in 1912.

Over the next two years, Bullard found a new life in Europe. He worked as a boxer and slapstick performer in a Black entertainment troupe in London. According to PBS, he also worked as a dock-worker, a target for an amusement park game, and he did other odd jobs. After a boxing match in Paris, Bullard realized that he enjoyed life in France, which was far less racist to Black people than his native Georgia.

“It seemed to me that French democracy influenced the minds of both black and white Americans there and helped us all act like brothers,” he wrote, according to the Smithsonian, and he wasn’t the only Black American to feel that way. Years later, after the start of World War I, some of the first American troops to arrive in Europe were members of the Black 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions, who were surprised to see how differently they were treated in war-weary France.

“Most French people who never left France, especially those in the countryside, had never seen a Black person,” Krewasky Salter, a retired Army colonel and historian, told Task & Purpose in 2020. “There was not the level of racism on the continent in France like there was in the U.S. because there was not this history of slavery in the country of France and the black population in France was minute compared to America.”

Bullard thrived in France, to the point where the 19-year-old émigré joined the French Foreign Legion to defend his new home when World War I broke out in 1914. Bullard led a machine-gun crew in the 1916 battle of Verdun, where he was recommended for the Croix de Guerre, a French military decoration rewarding feats of bravery. The young soldier was seriously wounded by an exploding artillery shell which ripped open his left thigh and narrowly missed his femoral artery, according to his biography, “All Blood Runs Red.”

While recovering, Bullard bet a friend $2,000 that he could enlist in the Aéronautique Militaire, the French flying service, according to the Smithsonian. It paid off, and by May 1917 he was a pilot with the Lafayette Flying Corps, a group of American pilots flying for the French during World War I.

Bullard was not the first Black military pilot in history. Other Black aviators preceding him flew for the United Kingdom, Italy, the Ottoman Empire, and even for France in that same conflict. But Bullard was the first Black American military pilot, which makes it all the more interesting that he could not fly for his own country. Bullard flew the Spad VII, a French-built biplane whose ruggedness and high diving speed made it one of the best aircraft of the war, according to the U.S. Air Force. Like many pilots, Bullard was a colorful character: he reportedly flew with a monkey named Jimmy, and on his plane was an insignia of a heart with a dagger running through it and the slogan “All Blood Runs Red,” according to the Smithsonian.

Bullard fought in a particularly intense aerial battle near Metz on November 17, 1917. It was 14 Lafayette aircraft against 10 German aircraft, according to his biography. The sky was filled with bullets and black smoke as the fighters circled and shot at each other. Bullard took a few hits to his fuselage and was diving back into the chaos when a black-painted German Fokker triplane emerged right in front of him.

Bullared “steadied the aircraft with his right hand on the control stick, and with his left he squeezed his firing button. Two dozen rounds hammered into the black shape,” read the biography. “Bullard could see bits of material flake off the plane and a wisp of black smoke began to trail from the engine.” But the experienced German pilot somehow pulled away and got on Bullard’s tail, sending bullets through his fuselage before the German’s engine finally failed from Bullard’s initial attack and corkscrewed down to Earth.

His own plane heavily damaged, Bullard didn’t last much longer before he had to make an emergency landing just inside friendly lines, where mechanics counted 96 bullet holes in the Spad VII. According to “All Blood Runs Red,” Bullard’s squadron commander told him he was lucky to survive, since he had been fighting with a pilot in the “Flying Circus” of Manfred von Richtofen (better known as The Red Baron), a group of the best pilots in the German military.

It was the first of two aerial victories that Bullard claimed, but neither were confirmed. Either way, it was the start of a long tradition of excellence in combat performed by Black American military aviators. That tradition stretched from Bullard to the famed Tuskegee Airmen of World War II and even to Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles “CQ” Brown Jr., an F-16 fighter pilot and the first Black service chief in U.S. history.

Unfortunately, Bullard’s flying career was short-lived. The aviator tried to join the U.S. Air Service after the U.S. entered the war, but he was tuned down due to racial prejudice, according to the Smithsonian. He then returned to the Aéronautique Militaire, but was booted back into the infantry after a confrontation with a French officer. But bigger and better things awaited Bullard. After the war, he owned a nightclub, an American-style bar and an athletic club in Paris. He mingled with luminaries like Langston Hughes, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Josephine Baker. Ernest Hemingway is said to have modeled an unnamed minor character after Bullard in his novel “The Sun Also Rises.”

His fighting days were not over though. As the Nazis gained power in Germany, Bullard joined a French counterintelligence network spying on Germans in Paris, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia. When Germany invaded France in 1940, Bullard again fought as an infantryman, but he was wounded by another artillery shell. Worried about being captured by the Nazis, he and his family escaped to New York City, where the largely unknown Bullard worked as a security guard, a longshoreman, and an elevator operator at Rockefeller Center.

All this might be considered enough accomplishments for one lifetime, but not for Bullard. He had “first known Negro military pilot” printed on his business cards, according to PBS, and in 1949 he was beaten by police in an altercation with a racist mob at a concert in New York. Bullard became sick of America after a bus driver ordered him to sit in the back of a bus, so he returned to France, where, in 1954, he was one of three men chosen to light the flame at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Paris, according to the Smithsonian.

France further showed its appreciation of Bullard by naming him a knight of the Legion of Honor in 1959, the highest order and decoration to be attained in France. Two years later, he died of stomach cancer in New York City, at the age of 66.

Though he received little recognition in his home country while he was alive, the U.S. showed its appreciation to Bullard over the next few decades. In 1994, nearly a century after Bullard’s birth, the U.S. Air Force posthumously commissioned him as a second lieutenant. Statues of Bullard were also erected at the National Air and Space Museum and the Museum of Aviation in Warner Robins, Georgia.

So there you go Dos Equis, there really was a “most interesting man in the world,” and his name was Bullard.

What’s hot on Task & Purpose

- Navy confirms video and photo of F-35 that crashed in South China Sea are real

- Who are the ‘Island Boys’ and why do US troops keep paying them for military shoutout videos?

- The Army is on the verge of picking a replacement for the M4 and M249

- Viral letter begging the military to ‘fix our computers’ reaches Pentagon leaders

- The Army’s new infantry assault buggy is a useless garbage pile

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.